REPORT OF AD HOC WORKING GROUP ON CURRICULUM REVISION

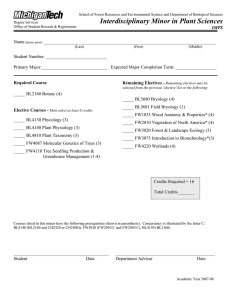

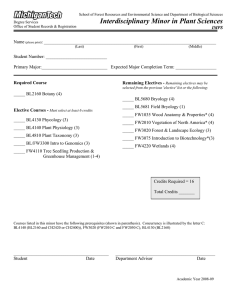

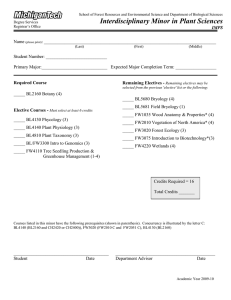

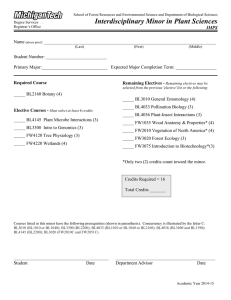

advertisement