Refugee Nutrition Information System (RNIS), No. 19 − Report on the Nutrition Situation of Refugee and Displaced Populations

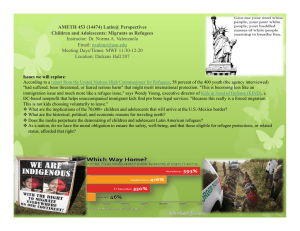

advertisement