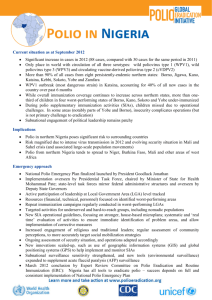

Report of the of the Initiative February 2012

advertisement