Trials in Critical Care: evidence you should know Dr. N.S. MacCallum

advertisement

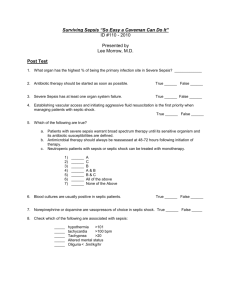

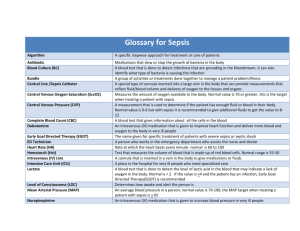

Trials in Critical Care: evidence you should know Dr. N.S. MacCallum MB BS PhD MRCP FRCA EDIC DICM Consultant in Intensive Care Medicine University College Hospital NS MacCallum 2010 Outline • introduction • sepsis • ARDS NS MacCallum 2010 Efficacy versus effectiveness Efficacy • result obtained in expert hands • ... under their conditions • ... with their enthusiasm Effectiveness • result obtained in general use how well it works under “real-world” conditions Don’t worry. I had the same thing and they cured me! how well something works in an ideal or controlled setting NS MacCallum 2010 Sepsis • definition • epidemiology • Early goal directed therapy • corticosteroids • activated protein C • cathecholamines • vasopressin NS MacCallum 2010 What is sepsis? A clinical syndrome that we all recognise… …but difficult to define. NS MacCallum 2010 ACCP/SCCM definitions Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) temperature • • SIRS defines an inflammatory response independent of its cause. >38°Cconditions: or <36°C The response is manifested by two or more of the following temperature >38°C or <36°C heart rate heart rate >90 beats/min respiratory rate >20 breaths/min or PaCO2 <4.3kPa white blood cell count >12,000 cells/mm3, <4,000 cells/mm3, or >10% immature (band) forms >90 beats/min respiratory rate Sepsis • >20 breaths/min The systemic response to infection; i.e. SIRS as a result of infection. Severe sepsis • Sepsis associated organ dysfunction, hypoperfusion, or hypotension. white bloodwith cell count Septic Shock • or PaCO2 <4.3kPa >12,000 cells/mm3 Sepsis with hypotension, despite adequate fluid resuscitation, along with the presence of perfusion abnormalities. <4,000 cells/mm3 Bone Chest 1992 101:1644 NS MacCallum 2010 Clinically useful definitions Sepsis - exaggerated inflammatory response to infection • The systemic response to infection; i.e. SIRS as a result of infection. Severe sepsis - sepsis + organ dysfunction • Sepsis associated with organ dysfunction, hypoperfusion, or hypotension. Septic Shock - severe sepsis + fluid-unresponsive low BP • Sepsis with hypotension, despite adequate fluid resuscitation, along with the presence of perfusion abnormalities. NS MacCallum 2010 Sepsis: a continuum of clinical and pathological severity Severe sepsis A clinical response precipitated by a non-specific insult SIRS + confirmed infection (later modified to suspected infection) Sepsis + organ dysfunction Highly sensitive definition, incidence dependent on aetiology Bone Chest 1992 101:1644 Septic shock Sepsis induced hypotension: • SBP <90mmHg or • ↓ >40mmHg (baseline) Severe sepsis + fluid unresponsive hypotension NS MacCallum 2010 The nature of the clinical problem • SIRS, sepsis, and MODS, together constitute the principle cause of death in adult intensive care units (ICU), with an associated mortality reaching 60%. • Sepsis recently ranked 7th ‘greatest killer’ in the US…on a par with AMI…but rising. • Disproportionate utilisation of resources: 47% of ICU bed days 33% hospital bed days Hospital length of stay has decreased, but is paralleled by an increase in discharge to longer term care facilities. • Economic burden - $16.7 billion in the USA alone. Angus CCM 2001 29:1303; Padkin CCM 2003 31:2332; Martin NEJM 2003 16:1546 NS MacCallum 2010 Comparison with other major diseases Mortality of Severe Sepsis Cases/100,000 Incidence of Severe Sepsis AIDS* Colon Breast CHF† Severe Cancer§ Cancer§ Sepsis‡ AIDS* Breast AMI† Cancer§ ‡Angus CCM 2001 29:1303; †Nat Center for Health Stat 2001; §Am Cancer Soc 2001; *AHA 2000 Severe Sepsis‡ NS MacCallum 2010 Epidemiology • Incidence and number of sepsis-related deaths are increasing in spite of an apparent decline in sepsis mortality. • Incidence of the sepsis syndromes ranges from 51 – 300 per 100,000 population per year Respiratory 40 - 70% Genitourinary 10% Abdominal 10% Bacteraemia 10-20% • 15-27% ICU admissions fulfil diagnostic criteria for severe sepsis in the first 24 hours Angus CCM 2001 29:1303; Brun-Buisson ICM 2004 30:580; Vincent CCM 2006 34:344 Padkin CCM 2003 31:2332; Martin NEJM 2003 16:1546 NS MacCallum 2010 Mortality • Sepsis • Severe sepsis • Septic shock 18 – 24% 29 – 47% 40 – 60% • Almost two-thirds of cases of severe sepsis are non-surgical. • The syndromes also have a significant impact on long term outcome, with an estimated 50% reduction in 5 year life expectancy. Alberti AJRCCM 2003 168:77; Brun-Buisson ICM 2000 26:S64; Angus CCM 2001 29:1303; Brun-Buisson ICM 2004 30:580; Padkin CCM 2003 31:2332; Martin NEJM 2003 16:1546; Vincent CCM 2006 34:344; Sundaraajan CCM 2005 33:71; Finfer ICM 2004 30:589 NS MacCallum 2010 Management • Source identification and control • Early antibiotics • Supportive therapy • Adjunctive therapy • Surviving Sepsis Guidelines 2008 NS MacCallum 2010 Source identification and control Identification • establish specific anatomic site of infection as rapidly as possible • evaluate if amenable to source control measures (e.g. drainage) Imaging • to confirm and sample any source of infection Control • implement source control ASAP • exception - infected pancreatic necrosis, where surgery best delayed • use intervention with least physiologic insult e.g. percutaneous rather than surgical drainage of abcess • remove intravascular access devices if potentially infected Early antibiotics Crit Care Med 2006; 34:1589–1596 • retrospective cohort; n=2731 with septic shock • survival to hospital discharge Anand Kumar et al. CCM 2006;34(6):1589-1596 • each hour of delay in antimicrobial administration over the ensuing 6 hours was associated with an average decrease in survival of 7.6% • despite a progressive increase in mortality with increasing delays, only 50% septic shock patients receive effective antimicrobial therapy within 6 hours of documents hypotension • Administration of an antimicrobial effective for isolated or suspected pathogens within the first hour of documented hypotension was associated with a survival rate of 79.9% Anand Kumar et al. CCM 2006;34(6):1589-1596 Early antibiotics: key points • begin iv antibiotics early and always within the first hour of recognizing septic shock and severe sepsis **mortality rises by 8% / hour delay** • broad spectrum, active against likely pathogens, good penetration into presumed source • combination therapy for pseudomonas and neutropenic patients • reassess daily • de-escalate to the most appropriate single therapy when susceptibility profile known • duration typically 7-10 days Supportive therapy I: Early goal directed therapy N Engl J Med. 2001 Nov 8;345(19):1368-77 • initiated treatment & resuscitation in the ED • 263 pts – treated for 6hrs • 500ml CSL every 30mins – CVP 8-12 • if Scv02 < 70% - RBC to Hct >30% • dobutamine Rivers – EGDT N Engl J Med. 2001 Nov 8;345(19):1368-77 Rivers – EGDT N Engl J Med. 2001 Nov 8;345(19):1368-77 NNT = 6 Rivers EGDT: Why did it work? Are there concerns? • short interval between admission and treatment • less patients developed CVS failure • standard group (0–7hrs) – – – – less time in ED less fluid 3.5 v 5L less blood 18.5 v 64.1% more sudden CVS death • treatment bias (?) • single centre Rivers EGDT: Key messages • standard tools for recognition of adequate resuscitation are ‘poor’ • early optimisation makes a difference - mainly fluid **begin protocolised resuscitation immediately if hypotension or lactate ≥ 4mmol/L** • new trials – ProCESS (NIH-funded trial) – ProMISE (NIHR) – ARISE (ANZICS) Supportive therapy II: Fluids / blood • no evidence base to support one type of fluid over another • albumin debate • hydroxyethyl starch debate • haemoglobin debate Albumin N Engl J Med. 2004 May 27;350(22):2247-56 • • • • RCT: 6,997 Australasian ICU pts saline vs. albumin albumin safe / equally effective as crystalloid small ns benefit from albumin in severe sepsis Albumin: SAFE study N Engl J Med. 2004 May 27;350(22):2247-56 Hydroxyethylstarch: VISEP trial N Engl J Med. 2008 Jan 10;358(2):125-39 VISEP trial • RCT; n=537, severe sepsis / septic shock • Ringer’s lactate vs. 10% HES (200/0.5) • stopped after first interim analysis • significantly more HES pts. developed ARF – dose dependant – doubled days requiring RRT • increased coagulopathy • mortality – no difference in early mortality (Days 1-28) – 27% increase in late mortality (Days 29-90) in HES group (ns) VISEP trial N Engl J Med. 2008 Jan 10;358(2):125-39 Hydroxyethyl starch • “Although the administration of hydroxyethyl starch may increase the risk of acute renal failure in patients with sepsis, variable findings preclude definitive recommendations” • maybe newer HES preparations (e.g. 6% HES 130/0.4) safer but currently little evidence to support their use in severe sepsis When to transfuse? N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-17 Haemoglobin: TRICC study Tx at Hb <7 Tx at Hb <10 N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-17 Key messages: Fluids • clear fluid - uncertainty continues • blood – do TRICC results hold true for leukodepleted transfusions? – early (e.g. Hct 30% in Rivers’) vs. late (7-9g/ dl) Hb? – what Hb in severe cardiorespiratory disease? Adjunctive therapy: steroids JAMA 2002;288:862-87 Effect of Treatment With Low Doses of Hydrocortisone and Fludrocortisone on Mortality in Patients With Septic Shock JAMA 2002;288:862-87 • RCT; n=300 • short synacthen test • randomly assigned to receive either hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone (n = 151) or placebos (n = 149) for 7 days • 1° outcome: 28 - day survival in patients with relative adrenal insufficiency (non-responders to the corticotropin test) Patients with relative adrenal insufficiency (non-responders) n=229 Hospital †: 61% vs 72% (p=0.04) Patients without relative adrenal insufficiency (responders) n=70 Hospital †: 69% vs 59% (p=0.75) Effect of Treatment With Low Doses of Hydrocortisone and Fludrocortisone on Mortality in Patients With Septic Shock JAMA 2002;288:862-87 • all patients, 28 day mortality, 63 % v 53% RR = 0.83; p = 0.04 • 28 day vasopressor withdrawal 40% placebo vs 57% treatment group in nonresponders ACTH; p = 0.001 Adjunctive therapy: steroids… NEJM 2008;358:111-24 Hydrocortisone Therapy for Patients with Septic Shock: Corticus trial NEJM 2008;358:111-24 • RCT ~500pts • 50 mg of intravenous hydrocortisone or placebo every 6 hours for 5 days; the dose was then tapered during a 6day period. • Primary outcome was 28 day mortality among patients who did not have a response to a corticotropin test. Hydrocortisone Therapy for Patients with Septic Shock: Corticus trial NEJM 2008;358:111-24 No difference between any study groups Annane vs. CORTICUS • Annane study, the patients had higher SAPS II scores at baseline, and there was a much higher rate of death at 28 days in the placebo group (61%, as compared with 32% in Corticus study). • enrollment in the Annane study was allowed only within 8 hours after fulfilling entry criteria, as compared with a 72-hour window in Corticus study. • CORTICUS enrolled both steroid responsive andunresponsiev patients • fludrocortisone was not given to patients in Corticus study, since 200 mg of hydrocortisone should provide adequate mineralocorticoid activity. COITTS (Annane) Corticosteroid Treatment and Intensive Insulin Therapy for Septic Shock in Adults JAMA Vol. 303 No. 4, January 27, 2010 • To test the efficacy of intensive insulin therapy in patients whose septic shock was treated with hydrocortisone and to assess, as a secondary objective, the benefit of fludrocortisone • 509 adults with septic shock who presented with multiple organ dysfunction and who had received hydrocortisone treatment was conducted in 11 intensive care units in France. • Compared with conventional insulin therapy, intensive insulin therapy did not improve in-hospital mortality among patients who were treated with hydrocortisone for septic shock. The addition of oral fludrocortisone did not result in a statistically significant improvement in inhospital mortality Steroids: Key message • The short corticotropin test does not appear to be useful for determining the advisability of corticosteroid treatment in patients with septic shock • Studies have described the poor relationship between total and free cortisol levels and other issues concerning the dose, timing, and type of corticotropin. Current recommendation • Low dose hydrocortisone for severe septic shock unresponsive to vasopressors • No indication for ACTH test Adjunctive therapy: activated protein C NEJM 2001;344:699-709 Adjunctive therapy: Activated Protein C Anti-inflammatory ↓ cytokines ↓ selectin mediated adhesion Anticoagulant Inactivates Va and VIIIa Pro-Fibrinolytic Inhibits PAI-1 ↓ Thrombin Activatable Fibrinolysis Inhibitor activation 28 day mortality rate was 30.8 % vs. 24.7% p=0.005. NNT = 16 But…. aPC: Key message • early promise not subsequently fulfilled • EMA mandated a new placebo-controlled trial – PROWESS-SHOCK trial • more sophisticated use (eg targeting protein C levels) • efficacy vs. side effects aPC: NICE Guidelines • Drotrecogin alfa (activated) is recommended for use in adult patients who have severe sepsis that has resulted in multiple organ failure (that is, two or more major organs have failed) and who are being provided with optimum intensive care support. • The use of drotrecogin alfa (activated) should only be initiated and supervised by a specialist consultant with intensive care skills and experience in the care of patients with sepsis. Adjunctive therapy: insulin NEJM 2001; 345: 1359-67 Intensive Insulin Therapy in Critically Ill Patients (2001) • RCT; n=1548 SICU • intensive therapy targeted glucose between 80-110 mg/ dl (4.4-6.1 mmol/l) vs. the conventional range was 180-200 mg/dl (10.0 – 11.1 mmol/l) • primary outcome: death in ICU • Mortality 4.6% in the Intensive Glucose control group vs. 8.0% in Conventional glucose control group (p<0.04) (42% relative risk reduction) van den Berghe G. Intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2001; 345(19): 1359-67. NEJM 2001; 345: 1359-67 Intensive Insulin Therapy in the Medical ICU (2006) • RCT; n=1200 • same authors and same conventional and intensive parameters as the first study • primary outcome was death in hospital which was 37.3% in the intensive group versus 40% in the conventional group (p=ns) • some benefit in subgroup requiring critical care for 3 or more days Van den Berghe G.Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU. N Engl J Med 2006; 354(5): 449-61. Intensive versus Conventional Glucose Control in Critically Ill Patients The NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators N Engl J Med 2009;360:1283-97 March 26 2009 NICE-SUGAR study • >6000pts • Intensive 4.5 - 6.0 mmol/l • Conventional < 10.0 mmol/l • Stratified – Type of admission – surgical or non surgical – Region – Australia and New Zealand or North America • Staff were aware of allocation post randomization 2.6% difference @ 90days NNTH = 38 Acute lung injury / ARDS • protective lung ventilation • PEEP • fluid strategy ARDS: low TV ventilation ARDS: low TV volume ARDS: low TV ventilation 6 ml/kg 12 ml/kg ARDSnet: low TV key points • Trial stopped early - 861pts • reduced mortality in 6ml/kg group • 31.0 % vs 39.8 %, P=0.007 • increased ventilator free days • mean [±SD], 12±11 vs 10±11; P=0.007 Summary: Sepsis • • • • • • • prompt recognition early and appropriate antibiotic therapy ± surgical/radiological eradication of focus early and appropriate fluid resuscitation restoration of an adequate circulation restoration of an adequate BP adjunctive therapy Summary: ARDS • avoid ‘baro-volutrauma’ • ensure early adequate fluid resuscitation & oxygen delivery • ... thereafter try to avoid excess positive fluid balance • optimise PEEP to the individual patient may change daily Surviving Sepsis Campaign 2008 New guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock Consensus of international experts Crit Care Med 2008: 36; 296-327