concerns about what it considers to funding for good causes generated

LOTTERIES

‘Lottery creep’ and the threat to online gambling operators

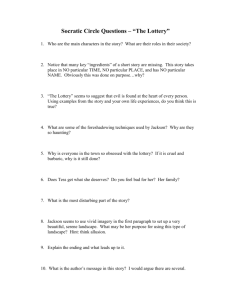

Last December the UK Department for Culture Media & Sport (‘DCMS’) issued a Call for Evidence on the lottery market. The Call for Evidence is particularly interesting because it raises questions about whether the

National Lottery could expand into non-lottery markets, such as for example by offering commercial online gambling and bingo products. Andrew Danson, Partner at K&L Gates, considers the threats the commercial betting and bingo sectors face from the lottery market.

The DCMS Call for Evidence (‘Call for Evidence’) is framed against a background of concerns that a blurring of the boundaries between commercial gambling, society lotteries and the National Lottery could have adverse impacts on the lottery market. However, there is a view that the commercial gambling operators have more to fear from the lottery sector than vice versa. In particular, Camelot, the exclusive licensee of the UK National Lottery monopoly, has stated publicly that it would like to see legislative and regulatory action against longstanding regulated betting products. Further, the Call for

Evidence raises the question of whether the National Lottery might be able to expand into bingo and other commercial gambling markets.

Threats to regulated commercial betting products

Revenues from the National

Lottery’s main Lotto product have been in decline for some time 1 .

This is typical of the experience of other national lotteries around the world, where this natural cyclical decline is well recognised 2 . Camelot is, quite rightly, seeking to address that decline, and has expressed concerns about what it considers to be current or future threats to the funding for good causes generated by the National Lottery. By extension, this applies equally to

Camelot’s own commercial profits.

A major cause of concern for

Camelot has been the Health

Lottery, which Camelot sought to challenge by Judicial Review of the

Gambling Commission (‘GC’) in

2012 3 . However, the Court found in favour of the GC and held that the Health Lottery was lawful.

Following that judgment, Camelot has raised the question of whether or not the law itself should be changed. More recently, Camelot has spoken out publicly against commercial gambling products, particularly betting on overseas lotteries. Andy Duncan, Camelot’s

Managing Director, addressed the

Lotteries Council Annual

Conference last year on the alleged

“encroachment by more and more gambling operators and their products, especially the proliferation of lottery derivative products enabling consumers to place wagers on the outcome of lotteries to win large jackpots,” 4 and Camelot’s written evidence to the DCMS Select Committee last year stated ‘we believe that […] all betting on lotteries and lotterystyle draws […] should be prohibited under UK law.’ 5

In its Call for Evidence, DCMS sought further information on whether ‘the emergence of lotterylike betting products and betting on lotteries (in permitted circumstances) creates risks or opportunities that need to be addressed.’ Having received market advice from the GC, DCMS stated in the Call for Evidence that ‘we can find no evidence that these

[lottery style commercial gambling products], tiny by comparison, are having any effect on the National

Lottery sales.’ That market advice from the GC stated that any larger impact on the National Lottery in the future, not just from commercial betting products, but from umbrella society lottery schemes (like the Health Lottery) and commercial betting products combined, is ‘unlikely, given the considerable commercial barriers.’

Camelot or others may yet produce evidence that might indicate a different impact or threat. However, additional evidence provided by, and an economic study commissioned by, businesses in the commercial betting sector and submitted in response to the Call for Evidence, supports the view that lottery betting presents no current competitive threat to the National

Lottery, nor is it likely to in the future.

In addition to evidential issues, there may be EU law barriers to taking further legislative or regulatory action against betting on overseas lotteries or other numbers games. For example,

Article 106(1) of the Treaty on the

Functioning of the European

Union (‘TFEU’) prohibits Member

States enacting or maintaining in force any measures contrary to rules contained in the Treaties, including Article 102 (abuse of dominance). If the UK

Government were to seek to legislate or regulate further against betting on lotteries, and thereby extend the National Lottery’s monopoly, that may constitute a breach of Articles 106(1) and 102 6 .

Furthermore, Article 56 TFEU prohibits restrictions on the freedom to provide services within the EU, unless they are justified by

EU-law compliant objectives, and are proportionate 7 . In this case, the objectives of increasing the funding of good causes, or preventing the reduction of tax revenues, have each been expressly rejected by the Courts as sufficient reasons to justify a restriction of

03

World Online Gambling Law Report - March 2015

LOTTERIES

the freedom to provide services 8 .

Finally, Article 4(3) TFEU imposes a duty of sincere cooperation on Member States to facilitate the achievement of the

Union’s tasks and refrain from any measure that could jeopardise the attainment of the Union’s objectives. The Government therefore would risk being in breach of Article 4(3) TFEU (in conjunction with Article 102 TFEU or Article 56 TFEU) if it was to implement measures to ban or limit commercial betting on overseas lotteries.

Only last year, the Government legislated to extend Section 95 of the Gambling Act, which prohibits

British-licensed betting operators and intermediaries from taking bets on the outcome of the UK

National Lottery, to the entire

British-facing regulated betting industry 9 . In light of the difficulties outlined above, the Government could face challenges in the Courts if it were to propose further legislative or regulatory change adversely affecting commercial betting on overseas lotteries.

Potential entry into nonlottery markets

Perhaps the most surprising and intriguing question in the Call for

Evidence was: ‘How far is it appropriate for the National

Lottery to compete with, for example, commercial online gambling and bingo products, in order to maintain or improve returns to good causes?’

Increasing the suite of services offered by the national lottery monopoly provider has been a common way to try to address the decline in traditional draw-based lottery products, and the UK is no different. As noted in the Call for

Evidence, Camelot began offering scratchcards in 1995, and interactive instant win games in

2003, both of which are recognised

04

Too much

Government support for the state monopoly’s exclusive licensee in facilitating its entry into a new gambling market currently occupied by commercial operators could constitute state aid, which the

Government will likely wish to avoid as presenting a higher risk to consumers than traditional drawbased lotteries.

There is, of course, nothing inherently wrong in Camelot seeking to grow its commercial profits, and increase National

Lottery revenues for good causes, by entering new areas. However, there are some legal issues that may be relevant. Having been the holder of the exclusive National

Lottery licence for 20 years,

Camelot has, by virtue of that state-sponsored monopoly position, built up (to its great credit) a hugely trusted brand, an enormous marketing database, and what is considered to be an unmatchable distribution network.

If that brand, marketing database and/or distribution network were used to enter, for example, the bingo market, it could have a significant and detrimental effect on the existing regulated commercial gambling operators in that market.

In 2010, Camelot made an application to the (then) National

Lottery Commission (‘NLC’) for consent to offer a number of commercial services through its network of National Lottery terminals 10 . After a thorough consultation on the EU law and competition law issues, the NLC rejected Camelot’s application on the basis that it considered that there was a significant risk of

Camelot being considered to have an unmatchable advantage in the commercial services market by virtue of the use of National

Lottery networks, and of Camelot committing stand-alone abuses of its dominant position, such that the UK would be in breach of

Article 106(1) TFEU.

The EU law issues identified in that Ancillary Services case may still be considered applicable.

Further, too much Government support for the state monopoly’s exclusive licensee in facilitating its entry into a new gambling market currently occupied by commercial operators could constitute state aid, which the Government will likely wish to avoid.

Conclusion

The UK commercial betting and bingo sectors may face threats from the lottery market, potentially by means of further legislative or regulatory action to restrict the betting market, and/or the entry into bingo or other commercial markets by the National Lottery.

However, commercial operators may find some comfort in the law and the evidence.

Andrew Danson Partner

K&L Gates LLP, London andrew.danson@klgates.com

1. Gambling Commission National

Lottery Sales data, Market advice on the lottery sectors, Gambling Commission,

September 2014.

2. State Lotteries and Legalized

Gambling, Richard McGowan,

Greenwood Publishing, 1994; Market advice on the lottery sectors, Gambling

Commission, September 2014.

3. R (on the application of Camelot UK

Lotteries Ltd) v. Gambling Commission

[2012] EWHC 2391 (Admin).

4. Andy Duncan, 27 March 2014.

5. Written evidence by Camelot UK

Lotteries Ltd to DCMS Select

Committee, October 2014.

6. For example, see Case C-18/88 RTT v. GB-Inno-BM [1991] ECR I-5941;

Greek Lignite OJ 2008 C93/3; Ancillary

Services, below.

7. Joined Cases C-338/04 and C-

360/04, Placanica, paragraph 49, ECR I-

1891.

8. For example, see Case C-409/06

Markus Stoss and Case C-347/09

Dickinger.

9. Gambling (Licensing and Advertising

Act) 2014.

10. Ancillary Services case: http://www.

natlotcomm.gov.uk/assets-uploaded

/documents/decision-on-ancilliaryactivities-proposal_1299003254.pdf

World Online Gambling Law Report - March 2015