Document 13391298

advertisement

24.961 Stress-3 Stress in Windows

[1] Kager (2012): many languages restrict stress/accent to a window of two or three syllables at

the right or left edge of the word.

R. Kager / Lingua 122 (2012) 1454--1493

R. Kager / Lingua 122 (2012) 1454--1493

1461

1461

Elías-Ulloa

thesepatterns

patternsusing

using

a strictly

disyllabic

adjusting

the weight

of an

initialsyllable

closed syllable

Elías-Ulloa(2005)

(2005)analyzes

analyzes these

a strictly

disyllabic

foot,foot,

adjusting

the weight

of an initial

closed

preceding

another

to(LˈH)

(LˈH)bybymeans

means

Weight-to-Stress

and Grouping

Harmony

1990).

This weight

preceding

anotherclosed

closedsyllable

syllable to

of of

Weight-to-Stress

and Grouping

Harmony

(Prince,(Prince,

1990). This

weight

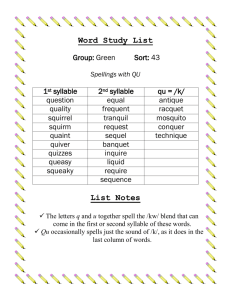

• right

edge: Aklan

binary, by

Modern

Greek,

Italian,

Spanish

ternary

adjustment

isisindependently

suffixal

allomorphy

is sensitive

to odd/even

parity treating

count, treating

adjustment

independently supported

supported by

a asuffixal

allomorphy

thatthat

is sensitive

to odd/even

parity count,

closed closed

syllables

as

light

odd

positions

(see

2009

forfor

an an

analysis).

Assuming

that the

disyllabic

foot-based

analysis analysis

is

syllables

light

ininodd

positions

(seeVaysman,

Vaysman,

2009

analysis).

Assuming

that

the disyllabic

foot-based

is

• asleft

edge:

Onati

Basque

binary,

Choguita

Raramuri

ternary

correct

and

alsothat

thatititcan

canbe

be generalized

generalized totoCapanahua,

these

languages

no longer

constitute

evidence

for a mixed

correct

and

also

Capanahua,

these

languages

no longer

constitute

evidence

for adefault.

mixed default.

•thethe

accent

location

in in

window

is determined

by

syllable

weight,

lexical encoding,

as

asspurious.

thirdS/I

S/I

language

Mathimathi

(Hercus,

1969),

quantity-sensitivity

is likelyis tolikely

be well

spurious.

ForFor

third

language

in StressTyp,

StressTyp,

Mathimathi

(Hercus,

1969),

quantity-sensitivity

to be

Goedemans(1997)

(1997)shows

shows that

that Mathimathi

stress

is is

entirely

morphologically

governed;

the appearance

of typologically

Goedemans

Mathimathi

stress

entirely

morphologically

governed;

the

appearance

of

typologically

distance

from

word

edge

uncommonquantity

quantitycriteria

criteria is

is due

processes

targeting

stemsstems

of specific

lengths.lengths.

uncommon

due to

tohistorical

historicalphonological

phonological

processes

targeting

of specific

All

three

P/U languages

listed in StressTyp

areor

Austronesian:

Javanese,

Malay,

and Ngada,

and their status in stress

•

accent

may

be

realized

by

stress

pitch

and

hence

is

a

n

abstract

quantity

All three P/U languages listed in StressTyp are Austronesian: Javanese, Malay, and Ngada, and their status in stress

typology is problematic. For Javanese, the status of word stress is controversial and descriptions are not uniform (Horne,

typology

ismaximal

problematic.

For

Javanese,

the

status

ofbword

stress

controversial

and

not

uniform2002)

(Horne,

• Poedjosoedarmo,

window

three

syllables

ut found

toisbe

at descriptions

both

edges are

(cf.

Gordon

1961;

1982;is

Ras,

1985).

In the Indonesian

spoken

bysymmetric

native speakers

of Javanese,

no systematic

1961;

Poedjosoedarmo,

1982;

Ras,

1985).

the Indonesian

spoken

speakers

of Javanese,

no the

systematic

phonetic

correlates of stress

have

been

found.InMoreover,

stress seems

notby

to native

be perceived

by Javanese

listeners:

• correlates

final syllable

canhave

be obligatorily

unstressedstress

but not

thenot

initial

syllable

phonetic

of contours

stress

been

seems

to be

perceived(Goedemans

by Javanese

the

manipulation

of pitch

of final

and found.

prefinalMoreover,

syllables failed to result

in different

perceptions

andlisteners:

van

manipulation

of pitch

contours

final the

andsituation

prefinalappears

syllables

result

in different

perceptions

(Goedemans

Zanten, 2007).

For varieties

of of

Malay,

to failed

be no to

less

complex

(van Zanten

et al., 2003;

Roosman, and van

Zanten,

2007).

varieties

Malay,

the situation

appears

to be no lessamong

complex

(van Zanten

al., 2003;

Roosman,

2006;

ZuraidahFor

et al.,

2008). of

Finally,

Ngadˈa

is most probably

miscategorized

P/U systems

since et

schwa

does not

[2]

examples

occur

in the final

according

to Arndt

(1933).

For probably

these reasons,

it seems rather

premature

to claim the

existence

2006;

Zuraidah

etsyllable

al., 2008).

Finally,

Ngadˈa

is most

miscategorized

among

P/U systems

since

schwaofdoes not

P/Uin

systems

with

mixedaccording

defaults. Into

sum,

the(1933).

evidence

forthese

opposite

defaults

in the form

of S/I

and P/U systems

rather

occur

the final

syllable

Arndt

For

reasons,

it seems

rather

premature

to claim is

the

existence of

Macedonian:

antepenult

stress

withforthe

exceptional

lexical

stress

in with

loanwords

No compelling

arguments

theevidence

existencefor

of stress

windows

P/Uweak.

systems

with mixed

defaults.remain

In sum,

opposite

defaults

innon-uniform

the form ofdefault

S/I andsystems.

P/U systems is rather

consider languages

have for

hierarchies

for intrinsic

prominence

(e.g.

a non-uniform

syllable weightdefault

scale).systems.

Weight

weak.Finally,

No compelling

argumentsthat

remain

the existence

of stress

windows

with

hierarchies

are well-known

for that

unbounded

stress languages

(such as

Kelkhar's Hindi

Kashmiri;

Prince

and Weight

Finally, vodéničar

consider

languages

have hierarchies

for intrinsic

prominence

(e.g.

syllable

weight

scale).

‘miller’

vodeníčar-ot

‘miller

def.aand

Smolensky, 1993). In case a weight scale system also imposes a stress window, the primary stress falls on the heaviest

hierarchies are well-known for unbounded stress languages (such as Kelkhar's Hindi and Kashmiri; Prince and

syllable occurring

within the window

-- a weight peak.

In case there is not a single

weight peak,

but two or three peaks

konzumátor

‘consumer’

konzumatór-i-te

‘consumers

def.’

Smolensky,

1993). In case a weight scale system also imposes a stress window, the primary stress falls on the heaviest

compete for attracting stress, the choice among these is made per default, similarly to languages with a binary weight

syllable

occurring

within Pirahã

the window

a weight

peak.

In case

not three

a single

weight

peak,in but

twostress

or three

contrast.

For example,

(Muran;-- Everett

and

Everett,

1984)there

has aisfinal

syllable

window

which

is peaks

compete

for attracting

the choice

is made per default, similarly to languages with a binary weight

predictable

according stress,

to a syllable

weight among

hierarchythese

in (15):

contrast. For example, Pirahã (Muran; Everett and Everett, 1984) has a final three syllable window in which stress is

Piraha (Everett & Everett 1984)

predictable

according

syllable

in (15): G = voiced)

(15) CVV

> GVV to

> a VV

> CVweight

> GVhierarchy

(C = voiceless;

1

(15)

2

3

4

5

CVV > GVV > VV > CV > GV

(C = voiceless; G = voiced)

Stress

falls on

1

2 the heaviest

3 of the

4 last three

5 syllables in the word. In the representations below, the stress window has

been marked by square brackets.

Stress falls on the heaviest of the last three syllables in the word. In the representations below, the stress window has

(16) a. 4-4-[3-2-1] ko.so.ii.gai.ˈtai

‘eyebrow’

been marked

by square brackets.

b. 4-[1-4-4]

ʔi.ˈtii.ʔi.si

‘fish’

(16)

c.

1-1-[1-4-3]

a. d. 4-4-[3-2-1]

1-[1-5-5]

b. e. 4-[1-4-4]

4-[1-4-3]

c. f. 1-1-[1-4-3]

4-[5-5-2]

d. g. 1-[1-5-5]

4-[4-2-4]

e. 4-[1-4-3]

Inf.case4-[5-5-2]

the heaviest

g. 4-[4-2-4]

(17)

ʔoo.hoi.ˈhoi.hi.ai

‘caterpillar’

ko.so.ii.gai.ˈtai

‘eyebrow’

pii.ˈhoa.bi.gi

‘frog’

ʔi.ˈtii.ʔi.si

‘fish’fuel’

ʔi.ˈsii.ho.ai

‘liquid

ʔoo.hoi.ˈhoi.hi.ai

‘caterpillar’

ʔo.ga.ba.ˈgai

‘want’

pii.ˈhoa.bi.gi

‘frog’

ʔa.pa.ˈbaa.si

‘square’

ʔi.ˈsii.ho.ai

‘liquid fuel’

syllable

in the word falls

outside the window, it fails to attract the primary stress:

ʔo.ga.ba.ˈgai

‘want’

ʔa.pa.ˈbaa.si

‘square’

a. 1-1-5-[4-3-4] pia.hao.gi.so.ˈai.pi ‘cooking banana’

b. 1-[2-4-3]

poo.ˈgai.hi.ai

‘banana’

In case the heaviest syllable in the word falls outside the window, it fails to attract the primary stress:

c. 1-[3-5-5]

kao.ˈai.bo.gi

‘jungle spirits’

(17)

a.

1-1-5-[4-3-4]

pia.hao.gi.so.ˈai.pi

‘cooking banana’

c.

1-[3-5-5]

kao.ˈai.bo.gi

‘jungle spirits’

The default stress position in Pirahã is rightmost. This is evidenced by windows that contain more than a single

b. syllable

1-[2-4-3]

‘banana’

heaviest

(i.e. a tie),poo.ˈgai.hi.ai

in which case the rightmost

of these is stressed.

(18)

a. [2-1-1]

bai.toi.ˈsai

‘wildcat’

b. [1-1-1]

pao.hoa.ˈhai

‘anaconda’ This is evidenced by windows that contain more than a single

The default

stress position

in Pirahã is rightmost.

5-[1-5-1]

‘pig’rightmost of these is stressed.

heaviest c.

syllable

(i.e. a tie),ba.hoi.ga.ˈtoi

in which case the

d. 1-[2-5-2]

kao.bii.ga.ˈbai

‘almost falling’

4-1-5-[3-4-3] bai.toi.ˈsai

ka.pii.ga.ii.to.ˈii

‘pencil’

(18) a. e. [2-1-1]

‘wildcat’

4-4-[3-3-3]

ʔo.ho.aa.aa.ˈaa ‘searching

intensely’

b. f. [1-1-1]

pao.hoa.ˈhai

‘anaconda’

[4-4-4]

ko.ʔo.ˈpa

‘stomach’

c. g. 5-[1-5-1]

ba.hoi.ga.ˈtoi

‘pig’

h. [5-5-5]

gi.go.ˈgi

‘what about you’

d. 1-[2-5-2]

kao.bii.ga.ˈbai

‘almost falling’

e. 4-1-5-[3-4-3] ka.pii.ga.ii.to.ˈii

‘pencil’

Kager, René. “Stress in Windows: Language Typology and Factorial Typology.” Lingua 122, no. 13

f.

4-4-[3-3-3]

ʔo.ho.aa.aa.ˈaa ‘searching intensely’

(2012): 1454–93. © Elsevier. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative

g.

[4-4-4]

ko.ʔo.ˈpa

‘stomach’

Commons license. For more information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

h. [5-5-5]

gi.go.ˈgi

‘what about you’

1

words longer than two syllables (30f).

(30)

a.

b.

c.

d.

la.ˈqa.na

me.ˈloo.ni

ˈpaa.wits.ja

ˈsip.mas.mi

‘squirrel’

‘musk melon’

‘duck’

‘silver bracelet’

d.

e.

f.

ˈtaa.vo

ˈko.ho

ˈsi.kis.ve

‘cottontail’

‘wood’

‘car’

Azkoita Basque (Hualde 1998)

Two more examples of initial two syllable window systems that impose final unstressability are Oñati Basque, which

has lexical pitch accent (Hualde, 1999), and Aranda (Australian; Strehlow, 1942; Davis, 1988), which is based on syllable

- stress

rightmost

syllable

in trisyllabic window at left edge of word except that wordweight (the

presence

of syllable

onsets).

Turningfinal

now syllable

to initial three

syllable

windows constrained by non-finality, we already discussed a mixed lexical accent

is not

stressed

plus syllable weight system, that of Terêna, in section 2. An example of a purely accentual system is Azkoitia Basque

(Hualde,

accent in words longer than two syllables:

/gizon/

‘man’

‘the man-ABS’

(31) a. gi.ˈzo.na

c. /alargun/

‘widow’

gi.zo.ˈnai

‘the man-DAT’

a.lar.ˈgu.ne

‘the widow-ABS’

gi.zo.ˈna.na

‘the man-GEN+ABS’

a.lar.ˈgu.nei

‘the widow-DAT’

gi.zo.ˈna.kin

‘the man-COM’

a.lar.ˈgu.ne.na

‘the widow-GEN+ABS’

a.lar.ˈgu.ne.kin

‘the widow-COM’

gi.zo.'nan.tsa.ko ‘the man-BEN’

‘the widow-BEN’

a.lar.'gu.nen.tsa.ko

Kager, René. “Stress in Windows: Language Typology and Factorial Typology.” Lingua 122, no. 13

b. /on/

‘good’

(2012): 1454–93. © Elsevier. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative

ABS’

ˈo.na For more information,

‘the good

Commons license.

see onehttp://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

...

[3]Observe

analytical

to define

two

and over

three-syllable

window (/ˈo.na/ ‘the good one’, */o.ˈna/).

that options

strict non-finality

has

priority

(default) non-initiality

‘‘The accentual pattern of bisyllabic forms such as óna ‘the good one’ shows that when the application of both

•extrametricality

binary feet conditions

plus extrametricality

edge

syllable,

constraints

lapses, layered

would make ofthe

whole

domainrhythmic

unaccentuable,

initial on

extrametricality

is revoked.

Expressed

in below)

terms of ranked constraints, nonfinality is ranked above noninitiality.’’ (Hualde, 1998:108)

feet (see

•

problem noted by Green & Kenstowicz (1995) for foot-binarity plus extrametricality:

That is, on an analysis that attributes default third syllable stress to initial extrametricality (rendering the initial syllable

unparsable),

and final unstressability

to final extrametricality

(unparsability),

the former

the latter. This

extrametricality

must be “revoked”

in case final

syllable is strongest

inmust

wordoverrule

in Piraha:

ranking similarly applies to Hopi seen above, on the analysis that second syllable stress is due to initial unparsability.

(‘pii.ai).ia ‘scissors’ but ?o.gi.’ai ‘big’

•

same problem for OT: Non-Finality » Align-Ft-Right fails to license stress on ?o.gi.’ai

•

Green (1995) proposes Lapse constraint: *adjacent unstressed syllables not separated by

1476

a foot boundary: *(ss)ss#, *#ss(ss)

•

R. Kager / Lingua 122 (2012) 1454--1493

pathological

pattern:

in words(Eisner

of two or1997,

three syllables,

stress is free to fall on any syllable, whereas in longer words, stress is

entails

midpoint

pathology

Hyde 2008)

restricted

to fall on a non-peripheral syllable.

(49),

a candidate

with1454--1493

a right-aligned iamb satisfies LAPSE/PARSE-2, hence

1476

R. In

Kager

/ Lingua

122 (2012)

thedetermines

Lapse constraint

prevents

lexical

from

drifting

far from

the

lexical-accent

the outcome

because

FAITHstress

-ACCENT

dominates

thetoo

default

constraints.

pathological pattern: in words of two or three syllables, stress is free to fall on any syllable, whereas in longer words, stress is

edge of the word so that it remains within the window

(49)

Free

stress

in three syllable

forms

restricted

to lexical

fall on a

non-peripheral

syllable.

In (49), a candidate with a right-aligned iamb satisfies LAPSE/PARSE-2, hence

but determines

as the word

longer,

stressFwill

be

drawn

to the the

middle

ofconstraints.

the word

lexical- accent

thegets

outcome

because

AITH-A

CCENT

dominates

default

FAITH L APSE /

FT=

ALIGN /

/

to avoid a lapse on each

edge

word

-2 of the

PARSE

ACCENT

TROCHEE

WORD-L

(49)

*!

('

)

- [TD$INLE] no language attested has this bizarre system

*!

*

( ' )

*

*!

('

)

Free lexical stress in three syllable forms

*

*

(

'

)

[TD$INLE]

FAITH FT=

ALIGN L APSE /

/

/

-2

ACCENTof LAPSE

-L since any candidate with a strictly

PARSE

TROCHEE

WORD

In longer forms of four (or more)

syllables,

violation

/PARSE-2 will be

minimal:

) one more violation of LAPSE/P*!ARSE-2 than a candidate with a non-aligned foot, an ˈinternalˈ window

aligned foot('incurs

*! that heads a

* non-peripheral foot.

emerges that

stress to fall on any syllable

( restricts

' )

In longer forms

of LAPSE/PARSE-2 will be minimal:

since any candidate with a strictly

*!

*

(' )of four (or more) syllables, violation

(50)

aligned foot incurs

( ' ) one more violation of LAPSE/PARSE-2 than a*candidate with* a non-aligned foot, an ˈinternalˈ window

emerges that restricts stress to fall on any syllable that heads a non-peripheral foot.

Peripheral unstressability in four-syllable form: default overrules peripheral accent

(50) Peripheral unstressability in four-syllable form: default overrules peripheral accent

FAITH FT=

ALIGNL APSE/

/

/

FAITH L APSE/

FT=

ALIGN/

/

ACCENT

PARSE-2

TROCHEE

WORD -L

[TD$INLE]

PARSE-2

ACCENT

TROCHEE

WORD -L

*!

*

(' )

*!

*

(' )

*!

*

*

( ' )

*!

*

*

( ' )

*

*

(' )

[TD$INLE]

*

*

(' )

*

*!

*

( ' )

*

*!

*

( ' )

*!

*

*

(' )

*!

*

*

('

)

(51) Non-peripheral

*

*

( ' ) stressability*!in four-syllable form

*

*

*!

( ' )

L APSETypology

/

AITHFactorial

FT= LinguaA122,

LIGNno.

- 13

Fand

/

/ Windows: Language

Kager, René. “Stress

in

Typology.”

PinARSE

ACCENT

TROCHEE

WORD-L

-2 This

(2012):Non-peripheral

1454–93. © Elsevier.

All rights

reserved.

content

from our Creative

(51)

stressability

four-syllable

form is excluded

*

Commons license.

see http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

(' For

) more information, *!

L APSE

F*T=

ALIGN FAITH

*! /

* (/ ' ) /

[TD$INLE]

PARSE-2

ACCENT

TROCHEE

WORD

*!

* -L

2

extrametricality-based models with binary feet cannot account for stress windows naturally leads to a shift in the

attention to different mechanisms: anti-lapse constraints and ternary foot models, which will be discussed in sections

4.2 and 4.3, respectively.

4.2. Symmetrical anti-lapse constraints

[4] grid-only with anti-lapse constraints also faces this problem (Gordon 2002)

A second model is based on symmetrical anti-lapse constraints. Anti-lapse

(58)

a.

x

xxxx#

extended lapse

b.

x

xxx#

lapse

c.

constraints ban sequences of unstressed

1983; Selkirk, 1984). In an edge-based model,

that target lapses specifically in word

2002). Below, three configurations of grids

x

xx#

no lapse

Kager, René. “Stress in Windows: Language Typology and Factorial Typology.” Lingua 122, no. 13

(2012): 1454–93. © Elsevier. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative

Commons license. For more information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

A final three syllable window system has a high-ranked constraint banning extended lapse at the right edge, while a

Final

three-syllable

window:

» Faith-Accent

» Align-maximal window

for the symmetrical

final two syllable window

systems

bans regular

lapse at *Extended-Lapse-R

the right edge. To account

size of three syllables,Head-L

anti-lapse constraints that target extended lapses must be assumed for both edges.

The specific implementation of this mechanism will be a pure grid (PG) model, adapted from Gordon (2002). Gordonˈs

initial

three-syllable

window:

*Extended-Lapse-L

» Faith-Accent

» Alignoriginal set was simplified

by eliminating

constraints

that are

exclusively relevant

for iterative stress.

The resulting model

has the following constraint

set.

Head-R

-

1480

R. Kager

(2012)too

1454--1493

Extended-Lapse keeps

stress/ Lingua

from 122

drifting

far away from edge and then

Faith orwhile

Head-alignment

in the stress

window

extended lapse constraints,

in words of three locates

syllablesstress

long, placing

on any syllable will satisfy both anti-lapse

constraints simultaneously. This predicts window systems in which stress is free to fall on any syllable in a three syllable

word, on

the second

or third in Lapse

four syllable

words,are

but top-ranked

may only occur

onthe

the best

third window

syllable inisfive

syllable

words. This

Problem:

when

both Extended

constraints

then

one

in

window pattern is a specimen of ˈMidpoint Pathologyˈ (Eisner, 1997; Hyde, 2008:4), ˈa collection of situations where an

the middle of a word with five syllables

object is drawn toward a medial position in a formˈ.

(61)

Window reduced in words of length 4 and 5 syllables

/

'

[TD$INLE]

*!

'

'

/

'

'

'

***

**

*

*E XTENDED *E XTENDED FAITH -A CCENT A LIGN -HEAD-L APSE-L

-L APSE-R

R

*!

*!

'

*

*!

*

*!

'

/

'

*E XTENDED *E XTENDED FAITH -A CCENT A LIGN -HEAD-L APSE-R

R

-L APSE-L

/

*!

*!

*

*

*

*

****

***

**

*

Kager, René.

“Stress

in Windows:

Typology.”

Lingua

122,the

no.two

13 high-ranking anti-lapse

Strikingly,

words

longer

than fiveLanguage

syllablesTypology

regain and

theirFactorial

accentual

freedom:

since

(2012):

1454–93.

© Elsevier.

rights reserved.

This

content

excluded

from

ourjumps

Creative

CCENT

into activity again. This restores

constraints

can

no longer

both beAll

satisfied,

one must

give

way,isand

FAITH-A

Commons

morewindow:

information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

the initial

three license.

syllableFor

stress

(62)

Window- regained

in words of words

length 6a syllables

in four-syllable

lexical accent on the second syllable can survive

[TD$INLE]

/

*E XTENDED

-A CCENT

A LIGN

-HEAD

*E XTENDED

FAITH

since/ both extended

lapse

constraints

are

satisfied;

but

when

the word is five

'

syllables there is an extended

so a violation occurs

* lapse on the

*! right and

*****

-L APSE-L

-L APSE-R

R

*

**** satisfies both

- ' the candidate with accent placed

in the middle of word

*!

***

*!

**

*!

*!

But ' the window is regained when the word is longer*than five syllables since

*!

*!

'

'

-

extended

lapse constraints

*!

'

*

now among the competing candidates every word will violate one or the

other of

of the

Extended

Lapse

constraints

and hence

is patterns

a tie that

will be

The factorial typology

constraint

set for

pure grids contains

254there

window

in which

stress in five syllable

words is fixed on theresolved

middle syllable,

with

shorter

words

and/or

longer

words

obeying

a

window.

Among

these,

175 show fixed

by the lower-ranked faithfulness or alignment constraints

midpoint stress in five syllable words, while shorter and longer words have accentual freedom within a window (of two or three

syllables, in initial or final position). The most severe cases are of the following kind: an (initial or final) window of two syllables

is imposed on longer words, i.e. a window size defeated by the fixed midpoint stress in five syllable forms.6

Additional pathological window patterns arise by specific interactions of anti-lapse constraints targeting lapses of different

3 which words

sizes. For example, the high-ranked combination *LAPSE-L » *EXTENDED-LAPSE-R generates a window system in

of all lengths are subject to an initial two syllable domain, except that four syllable words have fixed stress on the antepenult.

Table (42) displays window reductions for all logically possible combinations of anti-lapse constraints for words of lengths of

two to seven syllables. The stress windows are indicated by square brackets. In each cell, the stress patterns are listed that

*!

'

*

Strikingly, words longer than five syllables regain their accentual freedom: since the two high-ranking anti-lapse

constraints can no longer both be satisfied, one must give way, and FAITH-ACCENT jumps into activity again. This restores

the initial three syllable stress window:

/

(62)

'

[TD$INLE]

*E XTENDED *E XTENDED

-L APSE-L

-L APSE-R

/

'

'

'

'

*

*

*

*!

*!

*!

'

FAITH -A CCENT A LIGN -HEADR

*!

*!

*!

*!

*!

*****

****

***

**

*

Kager, René. “Stress in Windows: Language Typology and Factorial Typology.” Lingua 122, no. 13

(2012): 1454–93. © Elsevier. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative

Commons license. For more information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

The factorial typology of the constraint set for pure grids contains 254 window patterns in which stress in five syllable

words is fixed on the middle syllable, with shorter words and/or longer words obeying a window. Among these, 175 show fixed

midpoint stress in five syllable words, while shorter and longer words have accentual freedom within a window (of two or three

Thus,

free-ranking of natural constraints predicts an unattested stress system in the typology.

syllables, in initial or final position). The most severe cases are of the following kind: an (initial or final) window of two syllables

is imposed on longer words, i.e. a window size defeated by the fixed midpoint stress in five syllable forms.6

[5] The

problem

is not just

limited

to lexical

can arise

more generally

in any

system

Additional

pathological

window

patterns

arise byaccent

specificbut

interactions

of anti-lapse

constraints

targeting

lapses of different

sizes.

For

example,

the

high-ranked

combination

*L

APSE-L » *EXTENDED-LAPSE-R generates a window system in which words

where the two opposite-edge lapse constraints dominate alignment (Stanton 2014); stress is

of all lengths are subject to an initial two syllable domain, except that four syllable words have fixed stress on the antepenult.

drawn

middle

ofwindow

word just

in case

remove

lapses

at both edges;

but inconstraints

longer words

thisof lengths of

Tableto

(42)

displays

reductions

foritallcan

logically

possible

combinations

of anti-lapse

for words

two

to

seven

syllables.

The

stress

windows

are

indicated

by

square

brackets.

In

each

cell,

the

stress

patterns

are listed that

is not possible and so the default edge orientation will reassert itself

arise under a specific ranking of a pair of anti-lapse constraints. This ranking has anti-lapse constraint in the vertical

dimension as the higher-ranked one, and the anti-lapse constraint in the horizontal dimension as the lower-ranked one:

*Lapse-L » *Lapse-R » Align-L

6

Ss

sSs Ssss Sssss

Ss

Sss sSss ssSss Ssssss

To be sure, window systems are attested in which the degree of accentual freedom is correlated with syllable number, without showing

Midpoint Pathology. For example, the pitch accent in Kyungsang Korean (Kenstowicz and Sohn, 2001) is restricted by a final two syllable window

in words*Extended-Lapse-L

of two or three syllables, whereas

accent is fixed on the »penult

in words of four or more syllables. This is not a case of Midpoint Pathology,

» *Extended-Lapse-R

Align-L

as five syllable words are not accented on the middle syllables; moreover, longer words (exceeding four syllables) do not regain accentual

freedom. Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

[6] Kager’s suggested solution is to represent the two and three-syllable windows with a weakly1482

/ Lingua

122foot

(2012)

1454--1493

layered foot: a ternary foot withR.a Kager

single

binary

inside.

Nonfinality is restricted to final

(64) unstressability.

Shapes of the Weakly Layered foot

[TD$INLE]

head + adjunct adjunct + head

no adjunct

binary head, trochee

([' ] )

( [' ])

(['

])

binarywhen

head,

iamb Layered

A stress window occurs

a Weakly

([ foot

' ] is

) obligatorily

( [ aligned

' ]) with a domain

([ ' ])edge. A two syllable window

unary

head

results when the adjunct

is disallowed,

and hence,

aligned with both

([' the

] ) head is doubly

( [' ])

([' ])foot edges.

(65)

Two syllable windows: adjunct disallowed

Kager,

René. “Stress in Windows:

Language

a. final

window

b. initial

windowTypology and Factorial Typology.” Lingua 122, no. 13

rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative

U ([σ (2012):

ˈσ]) # 1454–93.

([ˈσ])©#Elsevier.

I

#All([ˈσ

σ])

# ([ˈσ])

Commons license. For more information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

P ([ˈσ σ]) #

S # ([σ ˈσ])

Observe that the contrast of peripheral versus non-peripheral stress may arise either by manipulating the head's

Gen

is “hard-wired”

only

allowversus

a single

“adjunct”

syllable

either athe

left orof a DPS

dominance (trochaic

versus

iambic), or itstosize

(binary

unary).

Technically,

thison

involves

ranking

constraint above a right

foot form

constraint.

edge

of foot and the internal “head” foot is restricted to two syllables (cf. foot

A three syllable window emerges when an adjunct is allowed in the weakly layered foot, so that the head may be misbinarity)

aligned with one (but

not both) foot edges. As compared to two syllable windows, the number of representational

possibilities for- non-peripheral

increases.

Forateach

stress position, four representational options

amounts tostress

binary

feet with

mostnon-peripheral

one recursion

occur, as shown below.

-

(66)

Ito & Mester (2012) propose similar restrictions on the depth of recursion in phrasal

Three syllable

windows: adjunct allowed

phonology

a.

final window

U ([ˈσ])

#

([σ ˈσ])set:

#

Kager’s

(2012)

constraint

P

A

([ˈσ σ]) #

([ˈσ σ] σ)

b.

I

S

T

initial window

# ([ˈσ])

# ([σ ˈσ])

# (σ [σ ˈσ])

([σ ˈσ] σ) #

(σ [σ ˈσ]) #

(σ [ˈσ σ]) #

(σ [ˈσ])

([ˈσ] σ)

4

# ([ˈσ σ])

# (σ [ˈσ σ])

# ([ˈσ σ] σ)

# ([σ ˈσ] σ)

# ([ˈσ] σ)

# (σ [ˈσ])

Observe that the three-way stress contrast is representationally encoded as variation in four aspects of foot form: head

dominance, head size, head alignment, and foot size. Evidently, foot form variation is not random, but under control of

constraint interaction. Crucially, a weakly layered foot model of stress windows should not be combined with extrametricality

(of the final syllable unparsability type) as this would incorrectly predict four syllable window systems. (See Everett, 1988:233

for a similar argument based on Pirahã.) However, non-finality can be assumed as an unstressability requirement.

The following constraint set will be assumed:

(67)

Constraint set for the Weakly Layered Model

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

f.

g.

h.

i.

j.

HD-BIN

ALIGN-HD-L

ALIGN-HD-R

HD=TROCHEE

HD=IAMB

PARSE-SYL

ALIGN-WORD-L

ALIGN-WORD-R

NON-FINALITY

FAITH-ACCENT

Heads are binary under syllabic or moraic analysis.

Heads are left-aligned with feet.

Heads are right-aligned with feet.

Heads begin with strong syllable.

Heads begin with weak syllable.

Syllables are parsed by feet.

Words are left-aligned with a foot.

Words are right-aligned with a foot.

Stress must not fall on the final syllable.

A lexical accent should be realized as primary stress.

HD-BIN is the counterpart of FT-BIN in the binary model, and it is evaluated analogously. Analogously to assumptions

Kager, for

René.

Windows:

Typology

and violates

Factorial H

Typology.”

Lingua

122,

13 . The Weakly Layered

made earlier

the“Stress

binaryinfoot

model,Language

a monosyllabic

head

D=IAMB, but

not H

D=Tno.

ROCHEE

(2012): 1454–93. © Elsevier. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative

Model has no constraints requiring peripheral syllables to be non-parsed by a foot, as in the binary foot model; the only

Commons license. For more information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

constraint referring to the final syllable requires its unstressability: NON-FINALITY. To determine the side of the adjunct

with respect to the head, a pair of head-to-foot alignment constraints (67b--c) are assumed. In case both constraints are

high-ranked, the adjunct is suppressed, in which case the size of the foot equals the size of its head (i.e. maximally two

-

no lapse and clash constraints

-

word-to-foot alignment constraints keep main stress foot at an edge while separate

constraints on foot form locate the stressed syllable within this maximally trisyllabic

foot domain; in the “foot-free” model all constraints are constraints on stress since

there is no foot or grouping by hypothesis

-

the mid-point pathology does not arise in Kager’s model since no consistent ranking

of the constraint set will produce this syndrome: to get third-syllable stress in a five

syllable word with lexical accent, the constraints defining the default must dominate

Faith for lexical stress; but then they will also override lexical stress within the

window; if Faith for lexical accent is top ranked then lexical accent can surface

independent of the window

[6] Stanton (2014)

-

over-generation in the typology of grammars predicted with lapse constraints does

not automatically entail weakly layered feet or more generally metrical grouping

-

the evidence needed to motivate the ranking with both lapse constraints

undominated does not appear in the data readily available to the learner

-

thus, such grammars are theoretically possible but not reachable for learnability

reasons (a familiar argument form; cf. Lightfoot’s 1979 Degree-0 learnability)

-

to learn the ranking where Extended Lapse constraints are top-ranked, long words

(six or seven syllables) are needed and they will be much less frequent in most (nonagglutinating) languages compared to shorter words

-

for binary-lapse dominant constraints the long-word argument does not hold and the

claim is that it is difficult to infer the appropriate ranking change (aka the “credit”

problem) with the Gradual Learning Algorithm

-

other pathologies: given Kager’s 2001 constraints licensing lapses at the stress peak,

a possible ranking will shift location of main stress in odd-parity words to license a

lapse. But this is also not attested. (not clear if this bears on the grouping question)

5

Norwegian University

Science

Technology

& Utrecht

University

Non-intervention

constraints

and theand

binary-to-ternary

rhythmic

continuum

VioletaofMartínez-Paricio

& René Kager

!

!"

!

VioletaofMartínez-Paricio

& René Kager

Norwegian University

Science and Technology

& Utrecht University

Norwegian

of Science

andhead

Technology

& UtrechtatUniversity

1. Introduction

The

IL foot respects

locality,University

due to adjacency

of the

and its dependent

both levels of structure.

Ternary

rhythm

the dependents

phenomenon

being((10)0)

placed and

rhythmically

on every

syllableadjacent

or mora.

1. Introduction

Although

the top is

level

ofof

thestress

IL dactyl

anapest (0(01))

arethird

not linearly

[7] weakly-layered feet have been proposed for ternary stress rhythms (Kager & Martinez-Paricio

paradigm

caseisisthe

Cayuvava

(Key

1961,

1967),

stress

occurs

third

Introduction

Ternary

rhythm

phenomenon

stress

being

placed

rhythmically

onevery

everyto

third

syllablecounting

orfoot.

mora.

toA1.

the

head

syllable,

what

matters

for of

locality

is

thatwhere

the dependents

are on

adjacent

thesyllable

innermost

2014)

1

backward

from

the

word

end:

Ternary

rhythm

isisthe

phenomenon

of1961,

stress

being where

placed

rhythmically

on every

every

third

or mora.

A paradigm

case

Cayuvava

1967),

stress

occurs

on

syllable counting

The

IL foot

is equally

local

in its(Key

vertical

dimension:

an upper

bound

of two

layersthird

of structure.

classical grammar: dactyl (Sss) anapest (ssS) amphibrach (sSs)

A

paradigm

casetheis word

Cayuvava

backward

from

end:1 (Key 1961, 1967), where stress occurs on every third syllable counting

Since

headedness

varies

at

two levels, four IL feet‘inside

arise: of

a dactyl

(1)

3n

!"#$"#$%&$'(&$)*$+*

cow’ ((10)0), two amphibrachs ((01)0) and

1

backward

from

the

word

end:

Cayuvava (dactyl) ((Ss)s)

(0(10))

(0(01)). Importantly, all four

typesof

arecow’

typologically attested. The dactyl ((10)0)

(1) and

3nan anapest

!"#$"#$%&$'(&$)*$+*

‘inside

3n+1

ma.!ra.ha.ha.'e.i.ki

‘their

blankets’

occurs

Tripura !"#$"#$%&$'(&$)*$+*

Bangla and Cayuvava:5

‘inside of cow’

(1) in 3n

3n+1

ma.!ra.ha.ha.'e.i.ki

‘their

blankets’

3n+2 i.ki.!ta.pa.re.'re.pe.ha

‘the

water

is clean’

(8)

The

dactylma.!ra.ha.ha.'e.i.ki

((10)0) in Tripura Bangla and Cayuvava

3n+1

‘their blankets’

3n+2 i.ki.!ta.pa.re.'re.pe.ha

‘the water is clean’

3n+1

((#bi.$%&.s'&.na

3n

((()*+)*&+,-&+..#/-+$0&+10&

Another 3n+2

classicali.ki.!ta.pa.re.'re.pe.ha

example is Chugach Alutiiq ‘the

Yupik

(Leer

1985a,b,c), where stress falls on every

water

is clean’

syllable

inclassical

position

3n!1 (e.g.is"Chugach

as3n+1

on

the ma.(((ra.ha).ha).((#e.i).ki)

final

syllable

of words

of length

Another

example

Alutiiq

Yupik

(Leer

1985a,b,c),

where

stress3n+1.

falls 2on every

2, "5), as well

3n+2

((#2'.ma).l!).((s'.na)

2

Chugach

Alutiq

(amphibrach)

(sS)s)well as on

Another

classical

example

is "Chugach

Yupik

(Leersyllable

1985a,b,c),

where

stress 3n+1.

falls on

every

syllable

in

position

3n!1

(e.g.

the final

of words

of length

2, "5), as Alutiiq

(2)

3n+2 ((#o.nu).k'&.(((ro.ni).j'&"

ta.'qa.ma.lu.'ni

‘apparently

getting done’

3n

"

3n+2

i.ki.(((ta.pa).re).((#re.pe).ha)

syllable in position 3n!1 (e.g. "2, "5), as well as on the final syllable of words of length 3n+1.2

(2)

3n+2 ta.'qa.ma.lu.'ni

‘apparently

getting done’

‘he

stopped eating

Chugach 3n

Alutiiq a.'ku.tar.tu.'nir.tuq

instantiates the ‘left-branching’ amphibrach

((01)0),akutaq’

to be supported in §4.

(2)

3n+2 ta.'qa.ma.lu.'ni

‘apparently getting done’

3n

a.'ku.tar.tu.'nir.tuq

‘hehestopped

akutaq’

.)eating

is going

to hunt porpoise’

3n+1

ma.',ar.su.qu.'ta.qu.'ni

(REFL

(9)

The

left-branching

amphibrach ((01)0) in‘if

Chugach

Alutiiq

3n

a.'ku.tar.tu.'nir.tuq

‘he stopped eating akutaq’

3n+1 ma.',ar.su.qu.'ta.qu.'ni

‘if he (REFL.) is going to hunt porpoise’

3n+2 ((ta.#qa).ma).(lu.#ni)

A third example

is

Tripura

Bangla

(Das

2001),

where

falls

on alltosyllables

in position 3n+1 (e.g.

is going

hunt porpoise’

3n+1 ma.',ar.su.qu.'ta.qu.'ni

‘if he stress

(REFL.)

3n

((a.#ku).tar).((tu.#nir).tuq)

Bangla

(dactyl)

((Ss)s)

"A1, third

"4),Tripla

except

thatisfinal

syllables

are(Das

always

unstressed.

Bangla

2001),

where stress falls on all syllables in position 3n+1 (e.g.

example

Tripura

A

example

is Tripura

Banglaare

(Das

2001),

where stress falls on all syllables in position 3n+1 (e.g.

"1,third

"4),3n+1

except((ma.#3ar).su).(qu.#ta).(qu.#ni)

that

final syllables

always

unstressed.

(3)

3n+2 '-..ma.l!.!s..na

‘criticism’

"1, "4), except that final syllables are always unstressed.

(3)anapest

3n+2

'-..ma.l!.!s..na

‘criticism’

The

(0(01))

matches the /accentual

of Winnebago (Miner 1979, 1981).6 However,

3n

'o.nu.k..!ro.ni.j./

// distribution

‘imitable’

(3) that binary

3n+2 and

'-..ma.l!.!s..na

‘criticism’

note

ternary alternation both occur,

and the conditioning factors are poorly understood

3n

'o.nu.k..!ro.ni.j.//

//

‘imitable’

3n+1

'o.no.nu.!da.)o.ni.j.

‘unintelligible’

(cf. Hale &

Eagle 1980, Hayes

3nWhite'o.nu.k..!ro.ni.j./

/ 1995:350).

//

‘imitable’

3n+1 'o.no.nu.!da.)o.ni.j.

‘unintelligible’

Winnebago

(anapest)

(s(sS))

Ternarity

has

been

reported

for

a

handful

of

other

languages: Estonian (Hint 1973), possibly Finnish

3n+1

'o.no.nu.!da.)o.ni.j.

‘unintelligible’

(10)

The

anapest

(0(01)) in Winnebago

3

non-stress

languages

with

(Carlson

Sentani

(Cowan

and of

Winnebago

(Miner 1979).

Ternarity1978),

has been

reported

for 1965)

a handful

other languages:

EstonianTwo

(Hint

1973), possibly

Finnish

3n+1 (hi.(d4o.#wi)).re

‘fall in’

3

ternary

groupings

arereported

Gilbertese

&ofWinnebago

Harrison

1999)

andEstonian

Irabu Ryukyuan

(Shimoji

2009).

Ternarity

has been

for (Blevins

a1965)

handful

other languages:

(Hintnon-stress

1973),

possibly

Finnish

Two

languages

with

(Carlson

1978),

Sentani

(Cowan

and

(Miner

1979).

3n+2 (ho.(ki.#wa)).(ro.#ke)

‘swing (noun)’

3

Two non-stress

languages

with

(Carlson

1978), Sentani

(Cowan 1965) and&Winnebago

(Miner

ternary

groupings

are Gilbertese

Harrison

1999)

and1979).

Irabu

(Shimoji

2009).Local

The

dominant

metrical

analysis of(Blevins

ternary rhythm

involves

binary

feet Ryukyuan

and underparsing

(Weak

ternary3ngroupings

are Gilbertese (Blevins & Harrison

1999)

and Irabu Ryukyuan (Shimoji 2009).

‘swing

(verb intr.)’

Parsing;

WLP; (ho.(ki.#wa)).(ro.(ro.#ke))

Hayes 1995).

WLP

a parsing

mechanism

derivational

theory(Weak

(WLP-DT)

The dominant

metrical

analysis

of as

ternary

rhythm

involves in

binary

feet andmetrical

underparsing

Local

isThe

well-constrained

(by 1995).

virtue

of

locality)

and

typologically

it hastheory

been(Weak

shown

that

dominant

analysis

of ternary

rhythm

involvessuccessful,

binary

feethowever

and metrical

underparsing

Local

Parsing;

WLP;metrical

Hayes

WLP

as a parsing

mechanism

in derivational

(WLP-DT)

[8]WLP;

feet as

contexts

for

segmental

(cf. Kenstowicz

1993,

Vaysman

2008,

Davis

2009,

WLP

analyses

couched

in

Optimality

suffer

from

severe

shortcomings,

to

two

Parsing;

Hayes

WLP

asTheory

a phonology

parsing

mechanism

in derivational

metrical

theory

(WLP-DT)

is well-constrained

(by1995).

virtue

of locality)

and (WLP-OT)

typologically

successful,

however

it has

been due

shown

that

and many more)

constraint

types:couched

Gradient

and

Rhythmic

Licensing.

Asfrom

we will

explain,

these

problems

is

well-constrained

(by virtue

of locality)

and typologically

successful,

however

it has

been

shown

that

WLP

analyses

inAlignment

Optimality

Theory

(WLP-OT)

suffer

severe

shortcomings,

due to can

two

be

grouped

under

two

headings:

theoretical

(non-locality)

and

typological

anddefined

under-generation).

- couched

Davis

& Alignment

Cho

(2003)

distribution

aspiration

in

English

can

be

asdue

foot-initial

WLP

analyses

in

Optimality

Theory

(WLP-OT)

suffer

from

shortcomings,

to two

4 ofLicensing.

constraint

types:

Gradient

and

Rhythmic

As

we severe

will(over

explain,

these problems

can

o(t áto)),

(Mèdi)(t

er(ránne))an,

if

a foot-initial

adjunct

postulated:

(p and

constraint

Alignment

and isRhythmic

Licensing.

As we

will(over

explain,

problems can

be groupedtypes:

underGradient

two

headings:

theoretical

(non-locality)

typological

andthese

under-generation).

h

h

h

(T àta)(ma(góuchi))

be grouped under two

headings: theoretical (non-locality)

and typological (over and under-generation).

1

h

-

Onset in the adjunct? athómathon, authómatha, octophus

1

1

6

shown

(57),arewhere

wepreferred

provide the

tonal patterns

two arise

wordsonly

withtoheavy

These

ternaryinfeet

overall

to binary

feet; theoflatter

satisfysyllables.

exhaustivity

andwords

avoid

have

similar

length

(both

trisyllabic)

andsupporting

stress occurs

exactlybased

the same

syllables

(i.e. the

first

unary

feet (46).

Here

we are

provide

evidence

thison

proposal

on the

distribution

of tones.

and

differthe

in tonal

their patterns

tonal melodies:

(57a)

syllable

bears a reports

low tone,

Thethird).

data inStill,

(56) they

illustrates

in wordsinwith

all the

lightsecond

syllables.

Leer (1985c)

that

whereas

thecan

second

syllable

(57b)different

does not.

syllables

exhibit

one ofinthree

tonal patterns: they can bear a high tone (H), a low tone (L)

or, under

specific

circumstances,

do not words

receive

a particular

tone;

pitch

of these syllables

depends

(57)

Tone

patterns

in Chugach

Alutiiq

light andPortuguese

heavythe

syllables

Kenstowicz

& Sandalo

(2014:with

in

Brazilian

intensity/duration

measures

of

on tones

neighboring

(Leer positions:

1985c: 164).

Chugach

tone

is not

lexically

various stress

tonic

> pretonic

posttonic

medial

> final:

a. of !an.

ci.vowels

qu!a insyllables

b. Importantly,

ta!a. ta. >

!qa

specified, but! its !(s(Ss))s

distribution

is determined exclusively by metrical

structure (Leer 1985c, Hewitt

!

!

!

HL

H

H

¡H L falls on adjunct

Martinez-Paricio

(2014): Chugach-Alutiq pitch-accents;

1991, Rice 1992,

Martínez-Paricio

2013).

‘my father’

‘I’ll go out’

(56)

Tone patterns in Chugach Alutiiq words with all light syllables

A strictly stress-based account of the distribution of tones in Chugach fails to capture the tonal

!

a.

ta.!"qu. ma.words

lu. "niwith heavy syllables are

b.

pi.!"su.

qu.

ta. "qu. !ni the stress-based

(56a-d).

However,

intosyllables,

consideration,

differences

betweenwhen

these two forms,

since stress falls on taken

the same

yet their pitch patterns

! !

!

! !

! !

account

proves

inadequate,

being

unable

to

predict

the

presence

or

absence

of Llowvs.tones.

is

are different. However,

inH (57a)

(57b) This

can be

H

Lthe tonal

H difference between unstressed syllables

H L

shown

in (57), where

we provide

tonal patterns

of two

words

heavy

syllables.

These

words

‘If hewith

is going

to hunt’

‘apparently

getting

done’

straightforwardly

captured

withinthe

a model

that allows

reference

to(refl.)

recursive

metrical

structure.

In

have

length (both

areChugach

trisyllabic)

andquantity-sensitive

stress

occurs

on exactly

the reader

same syllables

(i.e.

first

thesimilar

recursion-based

analysis

of Chugach

stress, the

is referred

to the

Martínezparticular,

— and

possibly

other

c.we propose

a. "ku. ta.that

"mek

d. languages

a."ta. ka as well (see §4.3)— exploits a

and

third).(2013),

Still,

they

differ

their

melodies:

(57a)

the

syllable

a dependent

low

tone,

Paricio

which

builds

heavily

on Leer

(1985),

Rice

(1992)

and

(1993).

is important

!two

!inof

! second

!of aKager

distinction

between

types

foottonal

dependents:

(i) in

the

dependent

FtMin

andbears

(ii)What

the

H

¡

H

H

L

whereas

second

syllable

in is(57b)

does

not. a low

thethepresent

discussion

thatin

(i)Chugach

Chugach

feettone

are only

moraic

andonto

iambic

and (ii) heavy

syllables

offor

a FtNon-min.

More

specifically,

docks

an unstressed

syllable

that

‘kind of food’ (abl sg)

‘my

father’

15

an

of their

own.

These

assumptions

explain to

why

forms with

the same

is constitute

directly

byfoot

a! FtNon-min,

whereas

no two

specific

tone

is assigned

immediate

dependents

! Tone

! dominated

! iambic

!

!!!!

(57)

patterns

in

Chugach

Alutiiq

words

with

light

and

heavy

syllables

can beof

seen

from and

(56),illustrated

stressed

syllables

are

always

high,of

and

somelike

of them

H

number

syllables

pattern,

but in

different

number

morae

[ta!a.ta.!qa]

‘my father’

(59a)

ofAs

FtMin.

analysis

below

(58)

and

§3 are

thatup-stepped

forms

with(¡H).

light

a. This

!an.

ci. qu!ais stress

b.(59). Remember

ta!a.

ta. !qafrom

is up-stepped

whenfeet

it isin

preceded

by another

andand

there

is nosyllable

intervening

low

the two

syllables

contain

3n+2 (58a),

3n (3b,H 3d)

3n+1

forms,

asbetween

long as the

latterhighs

do

! IL!‘I’ll

!go out’

! leading

! to differences

and [!an.ci.qu!a]

(59b), display differences in footing,

in their tones.

H L of

H high tones to stressed syllables (i.e. footHheads)

¡His

(56c).

The an

attraction

common

in mixed

not

contain

even number

of syllables (cf. 58c). Note that this analysis

correctly

predicts

thatprosodic

in the

‘my

father’

‘I’ll

go

out’

As

illustrated

in

(59a),

the

form

[ta!a.ta.!qa]

contains

an

initial

heavy

syllable,

which

projects

its own

systemsofwith

tonenoand

1987;(58c).

Bickmore 1995; de Lacy 2002, 2006). Likewise,

absence

IL feet,

lowstress

tones(e.g.

will Goldsmith

occur in a word

up-stepping

of afoot.

Haccount

when

by another

(e.g.

H¡H)

common

in the literature

of

minimal

bimoraic

Sincepreceded

thethe

second

and thirdH

light, isthey

are

into

another

A the

strictly

stress-based

of

distribution

ofsyllables

tonesHH"

inare

Chugach

fails

to grouped

capture

the tonal

(58)

Forms with light syllables

tone

and intonation

(Goldsmith

1976;

Pierrehumbert

1980;

2002;

2004,unparsed

etc.) and

bimoraic

foot. Thethese

construction

of asince

ternary

footfalls

would

have

instead

leftGussenhoven

the yet

finaltheir

syllable

or

differences

between

two forms,

stress

on

the Yip

same

syllables,

pitch

patterns

a. ((ta. !qu)FtMin. ma)FtNon-min (lu. !ni)FtMin

be easilyHowever,

captured

by atonal

simple

rule or via

constraint

interaction.

Whatin is(57a)

puzzling

in Chugach

arecan

the

difference

between

unstressed

syllables

vs. (57b)

can be is

a different.

degenerate

foot,

! but none

! of these options

! are allowed in Chugach (Leer 1985c). Next, [!an.ci.qu!a]

the distribution of

while

some H

unstressed

aretoassigned

a Lmetrical

(e.g. thestructure.

third syllable

straightforwardly

captured

a model

that allowssyllables

reference

recursive

In

H low tones:

Lwithin

(59b) contains two heavy syllables (the first and third), each projecting a bimoraic foot. To avoid

in 56a),b.other

unstressed

syllables

do

receive

a other

particular

tone, their

pitch

an interpolation

particular,

we propose

that. qu)

Chugach

— not

and!qu)

possibly

languages

as well

(seebeing

§4.3)—

exploits a

. ni)

FtNon-min. ((ta.

FtMin

FtNon-min

degenerate ((pi."!su)

feet andFtMin

non-exhaustivity,

the third

mora

is adjoined to the preceding foot, resulting in an

between neighboring

the dependents:

fourth!syllable

in 56a,b).

If one

considers

thethe

data

in (56), a

distinction

between !twotones

types!(e.g.

of foot

(i)!the

dependent

of only

a FtMin

and (ii)

dependent

IL ternary foot. HOnce their

metrical

structure

is

considered,

we

can

understand

why

these

forms

L

H

L

non-structural

stress-based

explanation

for

the

distribution

of

tones

could

be

proposed.

Namely,

of a FtNon-min. More specifically, in Chugach a low tone only docks onto an unstressed syllable that it

displayc. different

tonal. patterns:

[(ta!aH)(ta!qa¡H)] (63a) does not present any instance of recursion and,

(a. !ku)

(ta. tone

!mek)docks

FtMin

FtMin onto every post-stress syllable that is not immediately followed

be dominated

argued

that

a low

is could

directly

by

a FtNon-min,

whereas no specific tone is assigned to immediate dependents

!

!

hence,

no

low

tone approach

occurs;

inwould

contrast,

inin[((!an

)ciL)(qu!a

)]distributions

(63b), anfrom

ILinfoot

is aligned

with

the

Hand

HRemember

a high

tone.

This

derive

the

words

with

light

syllables

ofby

FtMin.

This

analysis

is illustrated

below

(58)correct

(59).

§3

that

forms

with

lightleft

H

¡H

!tonal

!

edge of

the((a.

prosodic

and,(58a),

consequently,

the and

dependent

of the non-minimal

foot

syllables

IL

3n+2

3n (3b, 3d)

3n+1 syllable

forms, as long

as surfaces

the latterwith

do a

d.contain

!ta)feetword

.inka)

FtMin

FtNon-min

tone.an even

notlow

contain

! number!of syllables (cf. 58c). Note

27 that this analysis correctly predicts that in the

H

L

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

absence of IL feet, no low tones will occur in a word (58c).

(59)

Forms with heavy syllables

Heavy syllables

" light

in Chugach, those containing a diphthong or a long vowel, and a CVC syllable in

(58)

Forms

with

a. (ta

!a) (ta. syllables

!qa)

b. ((!a n) ci) (qu !a)

word-initial position"

(µ !qu)

µ) (µalways

µ) attract stress and hence, slightly

((µ alter

µ) µ)the

( µbasic

µ) footing. For details on

a. ((ta.

FtMin. ma)FtNon-min (lu. !ni)FtMin

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

28

H

¡H

H

L

H

H

L

H

of ternary

feet could propose an alternative analysis based on WLP, in which the second

Detractors

b. ((pi."!su)

FtMin. qu)FtNon-min. ((ta. !qu)FtMin. ni)FtNon-min

!

! would! then only dock onto unfooted syllables (e.g. Hayes

Low tones

syllable in (59b) !is left unparsed.

H

L

H

L

1995:345). However, as Hayes (1995:343) acknowledges, this proposal fails to explain why a form

7

c. (a. !ku)FtMin. (ta. !mek)FtMin

like (59b) favors a parsing [(!an) ci (qu!a)] over [(!an)(ci.qu!a)], given that the uneven iamb in the latter

!

!

H

!

form is less marked

from a¡Htypological perspective. !The recursion-based

account is preferable to a

Davis, Stuart & Mi-Hui Cho. (2003). The distribution of aspirated stops and/h/in American

English and Korean: an alignment approach with typological implications. Linguistics 41.

607–652.

Kager, René (2012). Stress in windows: language typology and factorial typology. Lingua 122.

1454–1493.

Martinez-Paricio, Violetta and Rene Kager. 2013. Non-intervention constraints and the binary-toternary rhythmic continuum. Utrech U ms.

Stanton, Juliet. 2014. Learnability shapes typology: the case of the midpoint pathology. MIT ms.

8

MIT OpenCourseWare

http://ocw.mit.edu

24.961 Introduction to Phonology

Fall 2014

For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms.