The Perspectives of Taylor, Gantt, and Johnson:

advertisement

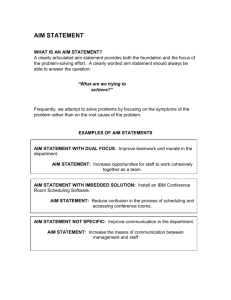

The Perspectives of Taylor, Gantt, and Johnson: How to Improve Production Scheduling Volume 16, Number 3 September 2010, pp. 243-254 Jeffrey W. Herrmann A. James Clark School of Engineering University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742 USA (jwh2@umd.edu) The challenge of improving production scheduling has inspired many different approaches. This paper examines the key contributions of three individuals: Frederick W. Taylor, who defined the key planning functions and created a planning office; Henry L. Gantt, who provided useful charts to improve scheduling decision-making, and Selmer M. Johnson, who wrote a highly influential paper on the mathematical analysis of production scheduling problems. The paper also describes the perspectives that these three represent and discusses how these perspectives can help one improve production scheduling. Keywords: Production Scheduling; Operations Research History 1. Introduction In manufacturing facilities, production schedules state when certain controllable activities (e.g., processing of jobs by resources) should take place. Production schedules coordinate activities to increase productivity and minimize operating costs. Using production schedules, managers can identify resource conflicts, control the release of jobs to the shop, ensure that required raw materials are ordered in time, determine whether delivery promises can be met, and identify time periods available for preventive maintenance. The two key problems in production scheduling are “priorities” and “capacity” (Wight, 1984). In other words, “What should be done first?” and “Who should do it?” These questions are answered by “the actual assignment of starting and/or completion dates to operations or groups of operations to show when these must be done if the manufacturing order is to be completed on time” (Cox et al., 1992). This is also known as detailed scheduling, operations scheduling, order scheduling, and shop scheduling. Unfortunately, many manufacturers have ineffective production scheduling systems. They produce goods and ship them to their customers, but they use a broken collection of independent plans that are frequently ignored, periodic meetings where unreliable information is shared, expediters who run from one crisis to another, and ad-hoc decisions made by persons who cannot see the entire system. Production scheduling systems rely on human decision-makers, and many of them need help dealing with the swampy complexities of real-world scheduling (discussed in detail by McKay and Wiers, 2004). 244 PERSPECTIVES OF TAYLOR, GANTT, AND JOHNSON Production scheduling appeared as a distinct management function in the era of scientific management. We are unaware of any important innovations in the area of production scheduling before that time. To improve production scheduling, organizations have adopted many decision support tools, from Gantt charts to computer-based scheduling systems (Herrmann, 2005, 2006a). Computer software can be useful. For example, in the 1980s, IBM developed the Logistics Management System (Fordyce et al., 1992), an innovative scheduling system for semiconductor manufacturing facilities that was eventually used at six IBM facilities and by some customers (Fordyce, 2005). Pinedo (1995) and McKay and Wiers (2006) discuss the design of scheduling decision support systems, and McKay and Wiers (2004) provide practical guidelines on selecting and implementing scheduling software. However, information technology is not necessarily the answer. Based on their survey of hundreds of manufacturing facilities, LaForge and Craighead (1998) conclude that computer-based scheduling can help manufacturers improve on-time delivery, respond quickly to customer orders, and create realistic schedules, but success requires using finite scheduling techniques and integrating them with other manufacturing planning systems. Finite scheduling uses actual shop floor conditions, including capacity constraints and the requirements of orders that have already been released. However, only 25% of the firms responding to their survey used finite scheduling for part or all of their operations. Integration is also difficult. Only 48% of the firms said that the computer-based scheduling system received routine data automatically from other systems, 30% said that a “good deal” of the data are entered manually, and 21% said that all data are entered manually. Starting in the 1950s, academic research on scheduling problems has produced countless papers on the topic. Pinedo (1995) lists a number of important surveys on production scheduling. Vieira et al. (2003) present a framework for rescheduling, and Leung (2004) covers both the fundamentals and the most recent advances in a wide variety of scheduling research topics. However, there are many difficulties in applying these results because real-world situations often do not match the assumptions made by scheduling researchers (Dudek et al., 1992). Studies of production scheduling in industrial practice have also led to the development of a business process perspective that considers the knowledge management and organizational aspects of production scheduling (MacCarthy, 2006). This perspective implies that it is important to design production scheduling processes that take into account knowledge management mechanisms and their setting within an organizational structure. This paper describes the key contributions of three individuals: Frederick W. Taylor, who defined the key planning functions and created a planning office; Henry L. Gantt, who provided useful charts to improve scheduling decision-making, and Selmer M. Johnson, who wrote a highly influential paper on the mathematical analysis of production scheduling problems. Each one took a different approach to improve production scheduling. This paper reviews their accomplishments and discusses the perspectives that they adopted. Each perspective looks at the task of production scheduling in a distinct way and thus proposes a different approach to improve it. Taylor changed the organization, Gantt created tools to improve decisionmaking, and Johnson solved optimization problems. 245 HERRMANN The purpose of this paper is to help production schedulers, engineers, and researchers better understand the history of production scheduling, show them that this history provides useful suggestions that are relevant today, and encourage them to develop more powerful approaches to improve production scheduling. The story of Gantt charts is commonly discussed in textbooks on scheduling, for Gantt charts remain an important type of diagram for representing schedules. The details of the lives and accomplishments of Taylor and Gantt are extensively documented elsewhere (appropriate citations are included below). Johnson’s algorithm is extremely well known. Despite the familiarity of these names, the contribution of this paper is to place these three luminaries into the story of production scheduling and to relate them to three corresponding perspectives on production scheduling. Although these perspectives may seem obvious to those who have worked in the area for many years, the author is unaware of any previous discussion of them or their roots in the history of production scheduling. For some, then, this material will be completely new, and presenting it in a single place, with a structure and context to understand its importance, should be valuable to many. 2. Taylor and the Planning Office Generally known for his fundamental contributions to scientific management in the late 1800s, Frederick W. Taylor’s most important contribution to production scheduling was his creation of the planning office (described in Taylor, 1911). His separation of planning from execution justified the use of formal scheduling methods, which became critical as manufacturing organizations grew in complexity. It established the view that production scheduling is a distinct decision-making process in which individuals share information, make plans, and react to unexpected events. In keeping with the idea of specialized work, there were many different jobs in Taylor’s planning office, from route clerk to speed boss to inspector (Parkhurst, 1912; Thompson, 1917). Wilson (2000) lists fifteen different positions. Here we briefly describe some of the positions that are most closely related to scheduling. The route clerk created and maintained routings that specified the operations required completing an order and the components needed. The instruction card clerk wrote job instructions that specified the best way to perform the operations. The production clerk created and updated a master production schedule based on firm orders and capacity. The balance of stores clerk maintained sheets (or cards) with the current inventory level, the amount on order, and the quantity needed for orders. This clerk also issued replenishment orders. The order of work clerk issued shop orders and released material to the shop. Recording clerks kept track of the status of each order by updating the route charts and also creating summary sheets (called progress sheets). The relative priority of different orders was determined by the superintendent of production. An interesting feature of the planning office was the bulletin board. There was one in the planning office, and another on the shop floor (Thompson, 1917). The bulletin board had space for every workstation in the shop. The board showed, for each workstation, the operation that the workstation was currently performing, the orders currently waiting for processing there, and future orders that would eventually need 246 PERSPECTIVES OF TAYLOR, GANTT, AND JOHNSON processing there. Thus, it was an important resource for sharing information about scheduling decisions to many people. White boards that serve the same purpose can be found today in many shops. Many firms implemented versions of Taylor’s production planning office, which performed routing, dispatching (issuing shop orders) and scheduling, “the timing of all operations with a view to insuring their completion when required” (Mitchell, 1939). The widespread adoption of Taylor’s approach reflects the importance of the organizational perspective of scheduling, a system-level view that scheduling is part of the complex flow of information and decision-making that forms the manufacturing planning and control system (McKay et al., 1995; Herrmann, 2004; MacCarthy, 2006). The rise of information technology did not eliminate the planning functions defined by Taylor; it simply automated them using ever more complex software that is typically divided into modules that perform the different functions more quickly and accurately than Taylor’s clerks could (see Vollmann et al., 1997, for a detailed description of modern manufacturing planning and control systems). 3. Gantt and His Charts The man most commonly identified with production scheduling is Henry L. Gantt, who not only worked with Taylor at Midvale Steel Company, Simonds Rolling Machine Company, and Bethlehem Steel but also served as a consultant to many other firms and government agencies (Alford, 1934). In Work, Wages, and Profits (originally published in 1916), Gantt explicitly described scheduling, especially in the job shop environment. He discussed the need to coordinate activities to avoid “interferences” but warned that the most elegant schedules created by planning offices are useless if they are ignored. To improve managerial decision-making, Gantt created innovative charts for visualizing planned and actual production. A Gantt chart is “the earliest and best known type of control chart especially designed to show graphically the relationship between planned performance and actual performance” (Cox et al., 1992). Gantt designed his charts so that foremen and other supervisors not in the planning office could quickly know whether production was on schedule, ahead of schedule, or behind schedule. His charts were improvements to the forms that Taylor developed for the planning office. Notably, he created charts for the personal use of supervisors in a format that they could carry with them at all times (unlike Taylor’s bulletin board, which was useful only when one was near it). Although they were part of Taylor’s broader manufacturing planning system, Gantt charts were meant to help individual managers make better decisions (Wilson, 2003). It is important to note that Gantt created many different types of charts, based on the specific needs of managers at American Locomotive Company, Brighton Mills, Frankford Arsenal, and other manufacturing organizations. He also created charts during World War I to improve the management of new ship construction and shipping operations (Porter, 1968). His charts attempt to make schedules useful. In Organizing for Work (originally published in 1919), Gantt gave two principles for his charts: one, measure activities by the amount of time needed to complete them; two, use the space on the chart to represent the amount of the activity that should have been done in that time. 247 HERRMANN Clark (1942) provides an excellent overview of the different types of Gantt charts, including the machine record chart and the man record chart, both of which record past performance. Of most interest to those studying production scheduling is the layout chart, which specifies “when jobs are to be begun, by whom, and how long they will take.” Gantt’s influential charts are ubiquitous in production scheduling and project management. Gantt was a pioneer in developing graphical ways to visualize the past performance of machines or employees, the current status of a shop, and schedules of future activities. He used time (not just quantity) as a way to measure tasks. He used horizontal bars to represent the number of parts produced (in progress charts) and to record working time (in machine records). Gantt’s work on charts to help supervisors reflects the view that scheduling is a decision-making process in which schedulers perform a variety of tasks and use both formal and informal information to accomplish these. We call this view the decisionmaking perspective. To perform this process well, schedulers must address uncertainty, manage bottlenecks, and anticipate the problems that people cause (McKay and Wiers, 2004). Gantt charts record and organize clearly the key data needed to perform these tasks. 4. Johnson and the Flow Shop Scheduling Problem According to Bellman and Gross (1954), one of the two researchers suggested that Selmer M. Johnson, their colleague at the RAND Corporation, investigate a bookbinding problem in which a set of books must be first printed and then bound (see also Dudek et al., 1992). The objective was to minimize the total time needed to finish all of the books. Johnson analyzed the properties of an optimal solution and presented an elegant algorithm that constructs an optimal solution. The published paper (Johnson, 1954) not only analyzed the two-stage flow shop scheduling problem (a basic result in the theory of production scheduling) but also considered problems with three or more stages and identified a special case for the three-stage problem. This paper was the first of a great deal of work on other versions of the flow shop scheduling problem and set a standard for the analysis of production scheduling problems of all kinds from the very beginning. Jackson (1956) generalized Johnson’s results for a two-machine job shop scheduling problem. Smith (1956) considered some single-machine scheduling problems with due dates. Both of these early, notable works cited Johnson’s paper and used the same type of analysis. Bellman and Gross (1954) addressed a slightly simplified version with a different approach while employing Johnson’s results. Conway et al. (1967) describe Johnson’s paper as an important influence, as it was “perhaps the most frequently cited paper in the field of scheduling.” In particular they noted the importance of its proof that the solution algorithm was optimal. Johnson’s paper “set a wave of research in motion” (Dudek et al., 1992). No other early work is so distinguished. Johnson’s paper epitomizes the problem-solving perspective, in which scheduling is an optimization problem that must be solved. A great deal of research effort has been spent developing methods to generate optimal production schedules, and countless papers discussing this topic have appeared in scholarly journals. Typically, 248 PERSPECTIVES OF TAYLOR, GANTT, AND JOHNSON such papers formulate scheduling as a combinatorial optimization problem independent from the manufacturing planning and control system in place. Schedule generation methods include most of the literature in the area of scheduling. Interested readers should see Pinedo and Chao (1999), Pinedo (1995), or similar introductory texts on production scheduling. Researchers will find references such as Leung (2004) and Brucker (2004) useful for more detailed information about problem formulation and solution techniques. Although there exists a significant gap between scheduling theory and practice (as discussed by Dudek et al., 1992; Portougal and Robb, 2000; and others), researchers have used better problem-solving to improve real-world production scheduling in some settings (see, for instance, Zweben and Fox, 1994; Dawande et al., 2004; Bixby et al., 2006; Newman et al., 2006). It may be that the results of production scheduling theory are applicable in some, but not all, production environments (Portougal and Robb, 2000). 5. Perspectives on Production Scheduling The historic work of Taylor, Gantt, and Johnson demonstrate the importance of three distinct perspectives on production scheduling: organizational, decision-making, and problem-solving. These three perspectives form a hierarchy, with the organizational perspective at the highest level, the decision-making perspective in the middle, and the problem-solving perspective at the lowest level. Moreover, this progression corresponds to the historical development of these perspectives. Taylor changed the organization, then Gantt developed charts to improve decision-making, and finally Johnson studied the optimization problem. Figure 1 illustrates this relationship in a conceptual way. Moving among these three perspectives corresponds to shifting one’s focus from the production planning organization to one person to one task. Thus, this hierarchy of perspectives does not correspond to a temporal or spatial decomposition of the manufacturing system. Instead, it is related to a task-based decomposition of the production scheduling activity. The layered structure of Figure 1 is not meant to correspond to the different time frames of production planning; instead, the layers are different ways to view production scheduling. Moving from one layer to the layer below is like zooming in on a scheduling decision, in some sense. In the organization layer, information moves from person to person through information-gathering and decision-making tasks. For example, one person sets a due date, another reviews it and negotiates a new one, and a third uses it to make a schedule. In the decision-making layer, the scheduler uses this information to solve current problems and avoid future ones. For instance, he checks the due date to evaluate the progress of an order, tries to get the due date changed, uses it to persuade someone to work on the order, and enters it into a scheduling routine. In the problem-solving layer, scheduling algorithms perform calculations on the data to generate and evaluate schedules. For instance, due dates can be used to sequence jobs and to measure tardiness. Consider, for instance, the example of a manufacturing facility with whom the author worked recently. The facility (part of a larger manufacturing organization) had many difficulties with delivering orders to customers on time. Often, managers 249 HERRMANN realized at the last minute that scheduled work could not be performed due to previously unknown problems with parts or the manufacturing processes. At that point, production planners would have to identify other work that could be done. Because this work was not on the schedule, obtaining the parts and setting up equipment delayed the time until it could commence. Despite the backlog, workers were underutilized. Acquisition manager Branch manager Monthly meeting Report w/o priorities Production scheduler Update weekly schedule Shop foreman Supervise production Report hours worked Discuss Weekly Finish and sign weekly schedule Schedule Report W/O status Production Engineer Organizational Perspective Schedule production Report Shop status Decision-Making Perspective Situation assessment Crisis identification Rote scheduling Scenario update Rescheduling Constraint relaxation Find future problems Problem - Solving Perspective M1 J1 M2 J4 J1 M3 J5 J4 J2 J6 J3 J2 J1 J3 J2 J6 J3 J6 Figure 1 Perspectives on Production Scheduling The facility managers were considering installing a scheduling software system that another facility in the organization had developed for its own use. The software had been developed originally as a workload planning tool to generate quotes and plan capacity. Over time, it had been expanded so that various managers and planners in the other facility could generate special reports about customer orders, material and resource requirements, the shop schedule, trouble tickets, and similar items. A study of the production scheduling process (conducted by the author and the facility’s production planners) showed that different individuals (planners and supervisors) in the facility maintained a variety of schedules and that workers could update the schedules directly when they had knowledge of problems that affected production. Unfortunately, this duplication and decentralization naturally meant a lack of coordination among the different areas in the facility and between the planners (who were scheduling the orders) and the shop floor personnel (who knew that those orders could not be done). 250 PERSPECTIVES OF TAYLOR, GANTT, AND JOHNSON The scheduling problem itself was not very difficult to describe. Although the facility was essentially a job shop, the routings were not long or complicated. Priorities were established based on customer importance and due dates. Capacity was sufficient for the workload. Conflicts were settled and schedules were updated in meetings with supervisors, planners, and managers, who did not complain about the complexity of the scheduling task. From the organizational perspective, it is clear that the facility described above had problems with the flow of information and decision-making authority. No one had a complete picture of the facility’s schedule, those creating schedules did not have the information that they needed to generate good schedules, and others were able to change the schedule without their approval. The facility managers viewed the problem from the decision-making perspective and therefore investigated purchasing software with the hope that new software would solve the facility’s problems by improving scheduling decision-making. From the problem-solving perspective, one would view this as a problem of scheduling a job shop with uncertain job ready times, which would lead one to develop and test algorithms to generate schedules that are robust to that uncertainty. These three perspectives suggest that there are multiple ways to improve production scheduling. Adopting the organizational perspective leads one to understand and improve the flow of information so that scheduling decision-makers have access to valuable, up-to-date, and accurate data and can share the results of their decisions to the right people at the right time (MacCarthy, 2006). Adopting the decision-making perspective leads one to setup daily scheduling routines for the schedulers, to provide the schedulers with training on the scheduling software, and to help schedulers improve their ability to identify future problems. Adopting the problem-solving perspective leads one to develop better mathematical models and algorithms that generate more efficient schedules. These approaches complement each other and can be combined as an integrative strategy that starts by adopting the organizational perspective and ends by considering the problem-solving perspective (Herrmann, 2006b). In general, those who wish to improve production scheduling must call upon a variety of techniques, identify the appropriate tools, and adapt them creatively for a particular situation. In addition, they should use multiple perspectives and involve the persons that have the problem in order to increase understanding of the realworld situation, which is an important objective (cf. Hall, 1985; Meredith, 2001). 6. Conclusions From a hundred years of work on improving production scheduling, Taylor, Gantt, and Johnson stand out for their original and influential contributions, which represent three important and distinct perspectives: the organizational perspective, the decision-making perspective, and the problem-solving perspective. As shown in this paper (cf. Figure 1), these perspectives can be positioned relative to one another in a hierarchical structure. Moreover, this structure is relevant to other decision-making systems and provides a comprehensive approach to attack the swampy complexities of real world messes, as the earliest work in operations research did (Miser, 1987). Because it addresses messy problems, requires the use of HERRMANN 251 multiple techniques, and focuses on understanding the situation, improving production scheduling is a challenging example of management engineering, an under-developed area of operations research that falls between the straightforward application of existing techniques and the research activities that add to our body of knowledge (Corbett and Van Wassenhove, 1993). The focus in this paper on these three reflects our emphasis on production scheduling and is not meant to deny the contributions of many other researchers to related areas. Like Gantt, Frank Gilbreth and others worked with Taylor to create and describe the field of scientific management (see, for instance, Gilbreth, 1914; and Hunt, 1924). Nevertheless, Taylor was acknowledged as the founder of the movement, and Gantt spent more effort on improving scheduling decision-making than his contemporaries did. Johnson was part of an active and important research community centered at UCLA and RAND. This group, whose leaders included Mel Salveson and James Jackson, created the foundations of operations management (Singhal et al., 2007). At the same time, Holt, Modigliani, Muth, and Simon were developing, with their colleagues at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, influential methods for aggregate production planning and forecasting (Singhal and Singhal, 2007). Other researchers studied not only scheduling problems like the flow shop problem but also transportation problems, industrial applications in linear programming, and related areas (Bellman, 1956). The use of computers for project scheduling (initially) and production scheduling was another important development (see, for example, O’Brien, 1969) because computers can automatically generate large and complex Gantt charts and can quickly execute the solution algorithms that researchers developed. This technology did not, however, introduce a new perspective on scheduling. We have identified and discussed the historical sources of three important perspectives on the problem. Because no one of them is sufficient alone, this paper describes the relationships between these perspectives and suggests a more comprehensive and effective approach that uses ideas from all three perspectives to improve production scheduling. Directions for future research include studies of different manufacturing settings to identify the most important aspects of the three perspectives discussed in this paper. From the organizational perspective, an important challenge is finding the correct balance of centralization and decentralization in the presence of modern information technology, which has revolutionized communication and data sharing. Likewise, Internet-based communication and sensor networks may provide new opportunities to improve decision-making by increasing production schedulers’ ability to foresee future problems and identify ways to avoid them. Case studies of applying the integrated approach discussed in this paper would be valuable as well. Finally, identifying additional perspectives, perhaps based on knowledge representation or cognitive processes, and developing corresponding tools would enhance this integrated approach. Acknowledgments: The author is grateful for the support of collaborators who provided opportunities to help improve production scheduling systems, the 252 PERSPECTIVES OF TAYLOR, GANTT, AND JOHNSON assistance of students who performed the work, and the encouragement of colleagues, especially Kenneth Fordyce, who shared their valuable time and ideas. The author also appreciates the useful comments of two anonymous referees. 7. References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. Alford, Leon P., Henry Laurance Gantt: Leader in Industry, 1934, ASME, New York. Bellman, Richard, “Mathematical aspects of scheduling theory,” Journal of the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 4(3), 1956, 168-205. Bellman, Richard, and Oliver Gross, “Some combinatorial problems arising in the theory of multi-stage processes,” Journal of the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 2(3), 1954, 175-183. Bixby, Robert, Rich Burda, and David Miller, “Short-interval detailed production scheduling in 300mm semiconductor manufacturing using mixed integer and constraint programming,” 17th Annual SEMI/IEEE Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing Conference, pages 148-154, Boston, 2006. Brucker, Peter, Scheduling Algorithms, Fourth Edition, 2004, Springer-Verlag, Berlin. Clark, Wallace, The Gantt Chart, a Working Tool of Management, second edition, 1942, Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, Ltd., London. Corbett, Charles J., and Luk N. Van Wassenhove, “The natural drift: what happened to operations research?” Operations Research, 41(4), 1993, 625-640. Cox, James F., John H. Blackstone, Jr., and Michael S. Spencer, editors, APICS Dictionary, 1992, American Production and Inventory Control Society, Falls Church, Virginia. Dawande, M., J. Kalagnanam, H.S. Lee, C. Reddy, S. Siegel, and M. Trumbo, “The slab-design problem in the steel industry,” Interfaces, 34(3), 2004, 215225. Dudek, R.A., S.S. Panwalkar, and M.L. Smith, “The lessons for flowshop scheduling research,” Operations Research, 40(1), 1992, 7-13. Fordyce, K., personal communication, 2005. Fordyce, K., Dunki-Jacobs, R., Gerard, B., Sell, R., and Sullivan, G., “Logistics Management System: an advanced decision support system for the fourth tier dispatch or short-interval scheduling,” Production and Operations Management, 1(1), 1992, 70-86. Gantt, Henry L., Work, Wages, and Profits, second edition, 1916, Engineering Magazine Co., New York. Reprinted in 1973 by Hive Publishing Company, Easton, Maryland. Gantt, Henry L., Organizing for Work, 1919, Harcourt, Brace, and Howe, New York. Reprinted in 1973 by Hive Publishing Company, Easton, Maryland. Gilbreth, Frank B., Primer of Scientific Management, 1914, D. Van Nostrand Co., New York. Reprinted in 1973 by Hive Publishing Company, Easton, Maryland. HERRMANN 253 16. Hall, Randolph W., “What’s so scientific about MS/OR?” Interfaces, 15(2), 1985, 40-45. 17. Herrmann, Jeffrey W., “Information flow and decision-making in production scheduling,” 2004 Industrial Engineering Research Conference, Houston, Texas, May 15-19, 2004. 18. Herrmann, Jeffrey W., “A History of Decision-Making Tools for Production Scheduling,” 2005 Multidisciplinary Conference on Scheduling: Theory and Applications, New York, July 18-21, 2005. 19. Herrmann, Jeffrey W., “A history of production scheduling,” in Handbook of Production Scheduling, 2006a, Springer, New York. 20. Herrmann, Jeffrey W., “Improving production scheduling: integrating organizational, decision-making, and problem-solving perspectives,” Proceedings of the 2006 Industrial Engineering Research Conference, Orlando, Florida, May 20-24, 2006b. 21. Hunt, Edward Eyre, Scientific Management since Taylor, 1924, McGraw-Hill, New York. Reprinted in 1972 by Hive Publishing Company, Easton, Maryland. 22. Jackson, J.R., “An extension of Johnson’s results on job lot scheduling,” Naval Research Logistics Quarterly, 3, 1956, 201-203. 23. Johnson, S.M., “Optimal two- and three-stage production schedules with setup times included,” Naval Research Logistics Quarterly, 1, 1954, 61-68. 24. LaForge, R. Lawrence, and Christopher W. Craighead, Manufacturing scheduling and supply chain integration: a survey of current practice, 1998, American Production and Inventory Control Society, Falls Church, Virginia. 25. Leung, Joseph Y-T., editor, Handbook of Scheduling: Algorithms, Models and Performance Analysis, 2004, Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton, Florida. 26. MacCarthy, Bart, “Organizational, Systems, and Human Issues in Production Planning, Scheduling and Control,” in Handbook of Production Scheduling, 2006, J.W. Herrmann, ed., Springer, New York. 27. McKay, K.N., F.R. Safayeni, and J.A. Buzacott, “An information systems based paradigm for decisions in rapidly changing industries,” Control Engineering Practice, 3(1), 1995, 77-88. 28. McKay, Kenneth N., and Vincent C.S. Wiers, Practical Production Control: a Survival Guide for Planners and Schedulers, 2004, J. Ross Publishing, Boca Raton, Florida. Co-published with APICS. 29. McKay, Kenneth N., and Vincent C.S. Wiers, “The human factor in planning and scheduling,” in Handbook of Production Scheduling, 2006, J.W. Herrmann, ed., Springer, New York. 30. Meredith, Jack R., “Reconsidering the philosophical basis of OR/MS,” Operations Research, 49(3), 2001, 325-333. 31. Miser, Hugh J., “Science and professionalism in operations research,” Operations Research, 35(2), 1987, 314-319. 32. Mitchell, William N., Organization and Management of Production, 1939, New York, McGraw-Hill. 254 PERSPECTIVES OF TAYLOR, GANTT, AND JOHNSON 33. Newman, Alexandra, Michael Martinez, and Mark Kuchta, “A review of longand short-term production scheduling at LKAB's Kiruna Mine,” in Handbook of Production Scheduling, 2006, Springer, New York. 34. O’Brien, James J., Scheduling Handbook, 1969, McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York. 35. Parkhurst, Frederic A., Applied Methods of Scientific Management, 1912, Wiley, New York. Reprinted in 1980 by Hive Publishing Company, Easton, Maryland. 36. Pinedo, Michael, Scheduling: Theory, Algorithms, and Systems, 1995, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. 37. Pinedo, Michael, and Xiuli Chao, Operations Scheduling with Applications in Manufacturing and Services, 1999, Irwin McGraw Hill, Boston. 38. Porter, David B., “The Gantt chart as applied to production scheduling and control,” Naval Research Logistics Quarterly, 15(2), 1968, 311-317. 39. Portougal, Victor, and David J. Robb, “Production scheduling theory: just where is it applicable,” Interfaces, 30(6), 2000, 64-76. 40. Singhal, Jaya, and Kalyan Singhal, “Holt, Modigliani, Muth, and Simon’s work and its role in the renaissance and evolution of operations management,” Journal of Operations Management, 25(2), 2007, 300-309. 41. Singhal, Kalyan, Jaya Singhal, and Martin K. Starr, “The domain of operations management and the role of Elwood Buffa in its delineation,” Journal of Operations Management, 25(2), 2007, 310-327. 42. Smith, W.E., “Various optimizers for single stage production,” Naval Research Logistics Quarterly, 3, 1956, 59-66. 43. Taylor, Frederick W., Shop Management, 1911, Harper and Bros., New York. 44. Thompson, C. Bertrand, The Taylor System of Scientific Management, 1917, A.W. Shaw Co., Chicago. Reprinted in 1974 by Hive Publishing Company, Easton, Maryland. 45. Vieira, Guilherme E., Jeffrey W. Herrmann, and Edward Lin, “Rescheduling manufacturing systems: a framework of strategies, policies, and methods,” Journal of Scheduling, 6(1), 2003, 35-58. 46. Vollmann, Thomas E., William L. Berry, and D. Clay Whybark, Manufacturing Planning and Control Systems, fourth edition, 1997, Irwin/McGraw-Hill, New York. 47. Wight, Oliver W., Production and Inventory Management in the Computer Age, 1984, Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, Inc., New York. 48. Wilson, James M., Scientific management, in Encyclopedia of Production and Manufacturing Management, 2000, Paul M. Swamidass, ed., Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston. 49. Wilson, James M., “Gantt charts: a centenary appreciation,” European Journal of Operational Research, 149, 2003, 430-437. 50. Zweben, M., and M. Fox, editors, Intelligent Scheduling, 1994, Morgan and Kaufmann, San Mateo.