Let the Government Contract: The Sovereign has the Right, and Good

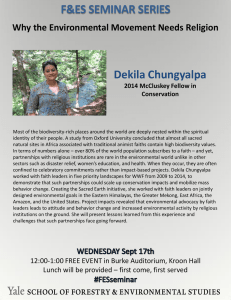

advertisement