Lincoln University Digital Dissertation

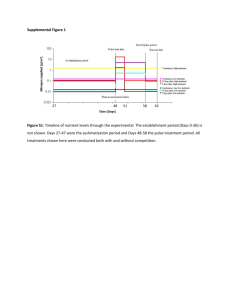

advertisement