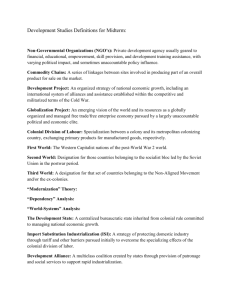

D e v e L o PM e N t

advertisement