Global Environmental Change and Small Island States and Territories:

advertisement

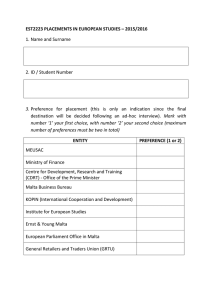

Global Environmental Change and Small Island States and Territories: Economic and Labour Market Implications of Climate Change on the Agriculture and Viticulture Sector of the Maltese Islands Tony Meli The salient points arising out of the Malta Environment & Planning Authority (MEPA) Environment report on Climate Change indicate five particular issues. The first of concern was that Malta's greenhouse gas emissions increased by 49% between 1990 and 2007. There were indications of particular vulnerability to sea-level rise and extreme events. The need to sustain efforts towards decoupling of economic activity from greenhouse gas emissions was recognized and adaptation measures would need to be adopted by various sectors and social groups. A parallel action would be the mainstreaming across all policy sectors to evaluate vulnerability and impacts with the aim of having a more resilient adaptation. It was concluded that there was a requirement to resort to development planning and related subsidiary policies and regulations as tools for mitigating and adapting to climate change needs. MEPA 2010 (The Environment Report 2008, SubReport 3, Climate Change) The latest Draft Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2013), of Working Group II in the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability confirms that human interference with the climate system is occurring whilst extreme weather and climate events including droughts and floods have significant impacts on economic sectors, natural resources, ecosystems, livelihoods, and human health. From a point of view of other species, it is indicated that many terrestrial plant and animal species have shifted their ranges and seasonal activities and altered their abundance in response to past climate change, and they are doing so now in many regions. It was confirmed that for rural areas, climate change will take place in the context of many important economic, social, and land-use trends. (IPCC, 2013, Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability) As socio-economic factors are important contributors to both the vulnerability and adaptability of human and natural systems, assessing climate impacts both in human and natural systems will necessitate a consideration of all factors influencing the systems. Notwithstanding rural concerns or otherwise, agriculture is considered responsible for an estimated one third of climate change. About 25% of carbon dioxide emissions, are produced by agricultural sources, mainly deforestation, the use of fossil fuel-based fertilizers, and the burning of biomass. Most of the methane in the atmosphere comes from domestic ruminants, forest fires, wetland rice cultivation and waste products, while conventional tillage and fertilizer use account for 70% of nitrous oxides. According to IPCC, the three main causes of the increase in greenhouse gases observed over the past 250 years have been fossil fuels, land use, and agriculture. (Climate Institute, http://www.climate.org/topics/agriculture.html) On IPCC’s Draft Report, the Executive Director of the European Environment Agency (EEA), other than pointing out that climate change was now visible in Europe and in all other regions of the world, also stated that the risks for Europe include: • • Increased risk of coastal flooding, erosion and economic losses due to accelerating sea-level rise Increased risk of inland flooding in many river basins due to projected increases in heavy rainfall 1 • • • Increased economic, ecological and social impacts due to stronger and more frequent heat waves, including health impacts, decreasing labour productivity, crop losses, ecosystem decline and increasing risk of wildfires in southern Europe Increased water restrictions due to significant reductions in water availability, particularly in southern Europe.(EEA, 2014, IPCC report shows growing risks from already-present climate change) The Joint Research Centre (JRC) indicates that agriculture accounts for only a small part of Europe’s gross domestic production (GDP), and the overall vulnerability of the European economy to changes affecting agriculture is low. However, it also indicates that agriculture is much more important in terms of land use, given that farmland and forest land cover approximately 90 % of the EU's land surface, rural population and income. Agriculture is a more significant in southern and southerly eastern European countries in terms of employment and GDP, and these countries will face a decrease in yields of 10% or more as a result of the shortening of the growing season and less rainfall. A likely trend for producers to alter practices and crop types by region as the climate changes was envisaged throughout Europe. (EEA, 2008 Impacts of Europe's changing climate — 2008 indicator-based assessment) In a Maltese context this would imply the need for additional organic matter to improve water retention together with the selection of hardier varieties or breeds that exhibit more drought and heat stress tolerance and earlier maturity such as the replacement of wheat by barley. Another obligation would be earlier, if not continuous, pest monitoring for disease control to compensate for mild winters with no cold break from pests or, if possible the provision of disease resistant varieties. In Malta’s Second UNFCC National Communication, the impact on cereals indicated that no models had been carried out for Malta, but for southern Europe models showed that winter wheat yields would not decrease where irrigation is not limiting, but there would be negative impacts when water was limited. Shortening of growing periods was likely to increase together with breakdown of organic matter, plant water stress and reduced crop yields. Potatoes, would benefit from elevated Carbon Dioxide (CO2) and elevated temperatures, however reduced yields were expected, particularly in arid conditions such as those in Malta. In the longer term, when the absence of water would become the critical factor, the final impact would result in the potato’s disappearance from Southern Europe. Impacts on vines were likely to result from an increase in temperature and from the evolution of rainfall distribution and efficiency. Impacts of increasing temperatures had already been felt in Spain and France where growers are moving to higher elevations. This would result in accelerated ripening that could inhibit production of good quality grapes. (MRA, UoM, 2010 The Second Communication of Malta to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) The University of Reading indicates a number of predicted effects of climate change on agriculture over the next 50 years: Carbon Dioxide, CO2 There is a very high probability that CO2 will increase from 360 ppm to 450-600ppm. In the case of enhanced CO2 on crop growth, physiological differences in C3 and C4 plants play on various uptake possibilities. Under CO2 enrichment, crops may use less water while producing more carbohydrates, whilst requiring more nitrogen. When plants absorb more carbon they grow bigger and more quickly. C3 plants take CO2 directly from the air during 2 carbohydrate production whereas C4 plants first concentrate CO2 first produce malate, which then enters the photosynthesis cycle. Thus, C4 plants will respond less to increased CO2 levels. C3 plants include wheat, rice, and soybean, whilst maize, sorghum, sugar-cane, millet, plus many pasture and forage grasses are C4 plants. Such effects would also need to be considered in conjunction with other climatic effects, particularly higher temperatures and soil moisture that could either enhance or negate potentially beneficial effects of increased CO2. Sea Level There also a high possibility of a 10-15 cm – increased in the south and offset in the north by natural subsistence/rebound. This will result in loss of land, coastal erosion flooding and salinisation of groundwater. The issue of the increase in sea level will not only pose a threat to agriculture in low-lying coastal areas, but also promote its elimination, particularly in small islands. The intrusion of seawater into coastal lowlands and aquifers such as Burmarrad, Pwales and Armier will create further hazards where drainage of surface water and ground water are impeded. This will, in turn, oblige usage of more salt tolerant crops in such areas. Warmer Temperatures and Heat Stress A rise of 1-2 Cº is expected with faster, shorter earlier growing seasons in a range moving north with increased evapotranspiration and heat stress. Warmer temperatures will also promote a quicker decomposition of organic matter, accelerate soil processes that determine fertility and provide more ambient conditions for insect pests. This could necessitate additional fertilizer/pesticide applications to sustain yields. In cases where soil moisture is scarce, both root growth and decomposition of organic matter would be comparatively more limited and would also increase vulnerability to wind erosion. Temperature is a crucial input in vine cultivation. If the temperature exceeds 35°C for a long period, red grapes would become stressed, with next to no tannins resulting. Malta had a local advantage for producing red wine, unlike white which grows in a wider variety of places. Currently, there are all the right conditions favouring red, except for water, though this, so far, is controllable with a requirement of 800m3 of water sometimes even up to 1,000m3per hectare of vines. Rain in spring is as yet not common, with prevalence in winter. Yet, an increased occurrence of later rain and higher temperatures would tend to result in a greater incidence of disease. Effectively wide fluctuations in yield are becoming noticeable - even down by 75%, but also even up to a fourfold drop in quality. The maturity date is crucial, but this is being affected by early and bad breaks of season occurring in mid-February rather than spring. The prevalence of a cold spell after bud break has resulted in up to 50% losses in Chardonnay production. (Roger Aquilina, oenologist, personal communication). Global warming will extend the length of the potential growing seasons in the middle and higher latitudes, obliging earlier crop planting, but this again will be a function of water availability. In Malta, practically half the land area is committed to dryland fodder production and there is but a small area of land under permanent crops with different fruits and vegetables, with the choice of crops has been dominated by market prices in conjunction with total water availability. An ageing farmer population, field size dominated by fragmentation, shallow soils, lack of organic matter, and a high pH has so far limited the introduction of new crops. Precipitation 3 Seasonal changes in precipitation of ±10% are expected. Changes in seasonal precipitation will affect rainfall, evaporation, runoff and soil moisture storage. A decrease in rainfall can result in moisture stress during germination, flowering, pollination and seeding that will harm plants. In the case of increased evaporation, salinisation of the soil with decreased yields and increased erosion will be the likely outcome with associated local drying of springs and aquifers. Associated variations in wheat production in Malta the past two years have been in the range of -10%, but even -50% was recorded. Similar yield losses were also observable in olive production. Two years ago, there was a negligible yield which however could be attributed to an off-year with up to 90% drop. Last year, however yield was around 33% and mild winters with lack of supporting rainfall together with a mild summer that probably also advantaged the presence of the olive moth were considered as contributory factors. Climate Extremes Climate variability and associated extreme meteorological events will see floods and droughts causing extreme physical damage to crops, other than possible exceeding tolerance of these crops to temperature extremes. Extreme rainfall will also result in increased soil erosion in these situations. Locally, most erosion in agricultural areas will occur in natural drainage depressions that have been cultivated, where rubble walls have not been maintained, where land is very exposed and where areas have a steep topography. Storminess and variability Predictions for increases in these climatic variables are considered low together with associated risk to damaging events that will affect crops and the timing of farm operations. However altered wind patterns can see to the spread of wind-borne pests and diseases. The combination of higher temperatures and increased wind could further result in susceptibility to fires following drought and thus also accelerate desertification processes. Main crop evaluation Reference to the NSO’s last Census of Agriculture of 2010 indicates 9 major crop typologies under Land Use for a total Utilisable Agricultural Area of 11,542.8 ha: Crop Type Forage/fodder crops Vegetables Kitchen Gardens Potatoes Vines Fruit & berry Olive Citrus Organic (Source NSO, 2012) Land Area (ha.) 5552.8 1730.5 1122.9 701.1 614.1 371.5 140.3 111.3 26.1 For all intents and purposes, forage constitutes a predominance of cereal crops, mostly wheat, harvested as hay for livestock fodder. NSO’s Agriculture and Fisheries 2012 further indicates tomatoes, lettuce, watermelon and cauliflowers as the crops with the highest tonnage sold through official markets and these are taken as representative of vegetables and kitchen gardens. Peaches constituted the most common of orchard trees, oranges are the most grown citrus and strawberries the most produced fruit. 4 Except for cereal production for fodder, all other crops are assisted with some form of irrigation that ultimately mitigates adverse climatic conditions. Discussions with local producers have indicated that cereals, olives and vines have so far demonstrated varying degrees of susceptibility to climatic actors, although, management factors are also relevant. Assumptions and standards In calculating inputs and outputs for wheat, olives and vines, the ultimate aim was to streamline data supported with good information. A crop budget will duly indicate the methodology and profitability of cropping operations. Inputs have been sourced from discussions with farmers and other technical persons closely involved either with the growing of, or trade in, a particular crop and primarily concerned practices and general machinery used. Similarly production has been based on average yields and average market prices. It is assumed that wheat farmers will own a sprayer and resort to contract services. Other farmers will additionally own a rotary cultivator, a van and other specialised items for their crop with associated depreciation costs. Given the fragmentation and associated small size factor, not all farmers are assumed to have tractors. Labour costs have been priced at the wage of a person in the grade of farmer with the Department of Agriculture with an additional 10% National Insurance contribution, at about €7/hour. Land rent is established at €175/ha for irrigated land and €84/ha for dry land. Economic Analysis As indicated under precipitation, both for climatic prediction, as well as through feedback from local farmers a minimum 10% fall in production is being assumed as the first financial display of climate change. Wheat production leaves a return of €221.52/ha which is reduced to €123.75 when a 10% decrease as a result of in climate change is assumed – effectively a 44.14% decrease in returns results. From a break even point of view there is a prevailing situation where with a 22.7% decrease in production, no revenue would result. Olive production leaves a return of €6777.28/ha which decreases to €3634.48 when a 10% fall for climate change is applied – again a 46.37% decrease in returns where with a 21.5% decrease in production, no revenue would result. Wine certification falls into two categories: DOK and IGT. Denominazzjonin ta’ Origini Kontrollata labels indicate that vintners followed the strict regulations possible to make that wine; the Indikazzjoni Geografika Tipika quality also confirms authenticity but is less taxing. Feedback attained on viticulture indicates a possible 50% loss pertaining to a false early break as well as but a 25% return due to higher temperatures. Other than these limitations, in the case of wine production two further economic scenarios prevail as to whether IGT or DOC wine would be produced with correlated volumes per hectare at 18,000:12,500 for IGT: DOC. Essentially IGT allows for more production. Additionally, there is a price range of €0.65 to €0.80. Results indicate that IGT production operates with returns of €719.50 for the €0.80/kg price but with a loss at €0.65/kg. With an assumed 10% climate change deduction the €0.80/kg return would also operate at a €677.28 loss. All DOC production entails a loss. IGT would break even with but a 5.9% fall for the €0.80/kg return. 5 Conventional Production of Wheat (Square Bales)/ha Variable costs 925.6 Fixed costs 133.8 Total costs € 1,059.4 Climate Change Factor INCOME 1,008.00 -10.0% Break Even 907.20 -22.7% 779.18 3% Tax on Income -30.24 -27.22 -23.38 VAT Refund 103.16 103.16 103.16 Subsidy on Less Fav. Area Production cost Revenue € 200.00 200.00 200.00 -1,059.40 -1,059.40 -1,059.40 221.52 123.75 -0.43 Conventional Production of Olives/ha Variable costs 20,492.42 Fixed costs 4,748.56 Total costs € 25,240.98 Climate Change Factor INCOME 32,400.00 3% Tax on Income -10.0% Break Even 29,160.00 -21.5% 25,304.40 -972.00 -874.80 -763.02 VAT Refund 390.26 390.26 390.26 Subsidy on Less Fav. Area 200.00 200.00 200.00 -25,240.98 -25,240.98 -25,240.98 6,777.28 3,634.48 20.26 Production cost Revenue € Conventional Production of Wine/ha Variable costs 9976.80 Fixed costs 3,943.50 Total costs € 13920.30 IGT .65to.80 INCOME - IGT 18000 0.8 INCOME - DOC 12500 0.8 3% Tax on Income DOC 14400.00 Climate Change Factor -10% Break Even 12960.00 -5.9% 13,550.40 10000 -432.00 -300.00 -388.80 -406.51 VAT Refund 471.90 471.90 471.90 471.90 Subsidy on Less Fav. Area 200.00 200.00 200.00 200.00 -13,920.38 -13,920.38 -13,920.38 -13,920.38 719.52 -3,548.50 -677.28 -4.59 Production cost Revenue € INCOME - IGT 18000 0.65 INCOME - DOC 12500 0.65 3% Tax on Income 11700.00 -10% 10530.00 0.0% 11,700.00 8125.00 -351.00 -243.80 -315.90 -351.00 VAT Refund 471.90 471.90 471.90 471.90 Subsidy on Less Fav. Area 200.00 200.00 200.00 200.00 -13,920.38 -13,920.38 -13,920.38 -13,920.38 -1,899.48 -5,367.23 -3,034.38 -1,899.48 Production cost Revenue € 6 As yet, these conclusions have been based on field observations and not on scientific trials, but essentially nowadays agriculture is the practical application of scientific principles. Collective results indicate that some 6307.2 ha pertaining to the wheat, olive and vine crop types or 54.64% of Malta’s total Utilisable Agricultural Area effectively could be rendered as not economically sustainable should productivity fall from about 23%. This impact could further exacerbate the push factor whereby the impact on farmer livelihoods would tend to detract them away from farming. Thus the onset of drier and warmer conditions in the Mediterranean region that could lead to more favourable pest conditions has become a potential risk to the very existence of rural farming systems in Malta. However the buck does not stop with the farmers. The provision of forage is closely linked to the dairy industry. Instead of purchasing local round bales that cost €30 and which weigh approximately 200 kg, the provision of imported hay at €250/tonne will be necessary – effectively a €100/t additional expense which could translate as a setback to profitability for livestock breeders, milk producers and finally consumers. In Malta, inextricably linked with the dairy industry are other livestock industries, particularly swine in the provision of animal feed. Given that logistics oblige the provision of specialised smaller ships to provide the basic components for animal feed, any reduction in quantities would necessarily result in a higher tonnage cost. Total gross production at producer prices by type of product at current market prices 2009 2010 Final production at producer 130,981 129,094 prices Livestock products 50,154 50,156 Beef 3,908 3,563 Pork 13,117 13,370 Sheep and Goats 425 395 Poultry 8,934 8,669 Rabbits 23,771 24,159 Animal products 25,337 24,089 Milk 18,299 17,982 Eggs 6,843 5,912 Other animal products 195 195 Crop products 47,647 47,857 Forage 3,831 3,769 Vegetables 29,889 30,146 Potatoes 4,708 4,962 Fruits 7,747 7,495 Flowers and seeds 1,256 1,269 Other seeds 216 216 Secondary activities 7,843 6,992 Wine 2,401 1,971 Cheese 5,442 5,021 Source NSO Economic Accounts for Agriculture: 2013 € 000 ±% 2013/2012 2011 2012 2013 132,427 133,946 138,222 3.2 49,906 3,371 13,186 384 8,586 24,378 24,874 20,303 4,376 195 50,899 4,677 28,149 8,971 7,100 1,786 216 6,749 1,892 4,856 48,812 3,556 11,486 381 8,660 24,729 28,955 21,921 6,824 210 48,708 4,314 29,243 5,822 7,270 1,844 216 7,470 2,663 4,807 51,313 3,512 14,030 363 8,608 24,800 30,176 22,073 7,893 210 49,605 4,633 28,840 6,770 7,417 1,730 216 7,128 2,538 4,590 5.1 -1.2 22.1 -4.8 -0.6 0.3 4.2 0.7 15.7 1.8 7.4 -1.4 16.3 2.0 -6.1 -4.6 -4.7 -4.5 In the case of production of fodder, grapes and olives, farmers could seek to cut down on expenses by cutting down on inputs, particularly fertiliser, but this again would affect both yield and quality particularly for wine and oil. The production of DOC wines has suffered a setback since prices fell from the €0.93-€1.05 level to the current €0.65 - €0.80 range. Trying to increase production by watering will affect the brix or sugar content, so ultimately farmers 7 will have a tendency for vine grubbing or removal after the 10-year commitment for government-aided development expires. It appears that olive production shall also necessitate awareness of climate change issues to help farmers adapt through better managerial practices. But, ultimately, oil and wine production command a niche in the local market that, if unavailable, would again oblige imports. Looking at the value of gross production for the sector as at 2013, and comparing the milk, forage and wine components of €29,244,000 to the €138,222,000 total, these three areas constitute at least 21.2% of the value of Malta’s agricultural production, and thus it may be assumed that at least this component could be impacted because of climate change. Thus, the response to damage to crops, with associated more difficult timing and management of agricultural operations, could be addressed by co-ordinated collective efforts raising awareness that promotes creative, practical and profitable responses, possibly including renewable energy, nutrient inputs, and soil management to the farming community. Agricultural adaptation options are grouped according to four main categories that are not mutually exclusive: (1) technological developments, (2) government programs and insurance, (3) farm production practices, and (4) farm financial management. (Smith & Skinner, 2001) An ongoing process recommended at EU level that is also supported by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) is the promotion of resource efficiency and supporting the shift towards a low carbon and climate resilient economy in the agriculture, food and forestry sectors through better risk management as well as support for climate change mitigation/adaptation through agri-environmental payments as well as through support for areas facing natural or other constraints. The lack of a critical mass precludes provision of local agricultural insurance. The selection of crop varieties more resistant to heat shock and drought is neither an ongoing local activity, given that the dimension of local agriculture generally imposes reliance on imported seed varieties, however going back to the old traditional method of growing mahlut, a mixture of wheat and barley, which at times when further mixed with vetches, sulla (legume) and wild oats, provides a more resilient crop mixture particularly with the more hardy barley and oats, could prove an agronomical sustainable approach. Similarly, crop rotation with the use of legumes, again with the traditional use of sulla, provides a good alternative to crop nitrogen requirements and would cut down on the manufacture of artificial nitrogen fertilizer which is ultimately requires high energy for production, with contribution to greenhouse gasses. On the other hand, resorting to more water saving approaches such as mulching, drip irrigation and building of reservoirs is on the increase. The latter is also supported by the EAFRD. Livestock breeders with manure digesters have just initiated to produce biogas to make electricity other utilizing it as fertilizer. Improving the effectiveness of pest, disease, and weed management practices through wider use of integrated pest management is becoming a more common practice more because of better financial and environmental practices than for climate change per se. Effectively, the size of holdings in Malta, where the number of agricultural holdings across Malta and Gozo in 2010 amounted to 12,529, covering 11,453 hectares of utilised agricultural area, results with 73.5% having a utilised agricultural area of less than 1.0 hectare each when some 18,539 persons were actively engaged in agricultural activity. Indeed, this emphasises the need for a collective effort in such a small island dimension to effectively monitor and tackle productivity, profitability and sustainability, including mitigation of climate change. 8 References Aquilina Roger, oenologist, personal communications – January 2014. EEA, 2008 Impacts of Europe's changing climate — 2008 indicator-based assessment IPCC, 2014, Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability MEPA 2010 (The Environment Report 2008, Sub-Report 3, Climate Change) MRA, UoM, 2010 The Second Communication of Malta to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. NSO, 2012 Census of Agriculture 2010 NSO, 2014 Economic Accounts Agriculture: 2013 Smith B., & Skinner M.W., 2001, Adaptation options in Agriculture to Climate Change: A Typology Climate Institute, http://www.climate.org/topics/agriculture.html Accessed 17/9/2014 University of Reading, Climate Change and Agriculture, http://www.ecifm.rdg.ac.uk/climate_change.htm Accessed 17/9/2014 9