LORCA’S GYPSY BALLADS “He was seen walking… Friends, carve

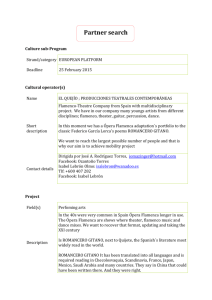

advertisement

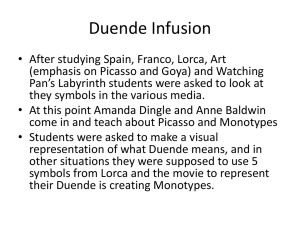

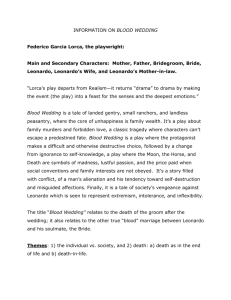

LORCA’S GYPSY BALLADS “He was seen walking… Friends, carve a monument of stone and dreams for the poet , in the Alhambra, near a fountain where weeping water for ever tells: the crime took place in Granada, his Granada!” (Antonio Machado) Life can’t be understood without death. It took three bullets in the neck to kill Federico García Lorca, but at the same time they gave him life as a poet and a dramatist of worldwide acclaim. Federico was born on the June 5th 1898 in a house in Trinity Street in Fuente Vaqueros. Very little is known about his early childhood. He had an obsession for silver cutlery and he also listened to countless Gypsy songs and ballads from his father and relatives. Federico said, “At the age of seven I went to Almería and I stayed at ‘El Colegio de Padres Franciscanos’ where I began to study music”. He grew up next to the family piano. One day, out of the blue, Federico began to recite. The musician had not lost his love of music, but had become a troubadour. Continuing to write and to recite poetry, Federico arrived at ‘La Residencia de Estudiantes’ in Madrid during the late spring of 1919, where he gave a recital, as a kind of audition to enter the institution. A year later saw the first production of The Butterfly’s Evil Spell. The play was a fiasco. Catalina Bárcena dressed as a cockroach asked herself ‘What do I have in my head?,’ to which a joker replied “a pair of horns!”. Manuel Machado wrote in La Libertad of Madrid, -‘Mr. García Lorca should, in the future, only write verse’-. In 1921 Lorca published his first book of poems. His play Mariana Pineda had its premiere in 1927 in Barcelona, featuring Margarita Xirgu and a set designed by Salvador Dalí. Yet it was in 1928 that The Gypsy Ballads appeared in shop windows, a tiny book of poems which made Lorca a famous poet. The Gypsy Ballads is, as Lorca called it, the poem of Andalucía. The book starts with two invented myths: the moon as a mortal dancer and the wind as a satyr. The book’s greatest triumph is its appraisal of Gypsy life. In the past, authors like Prosper Mérimée and Washington Irving had been fascinated by the Gypsy world, but it was Lorca who said, “The Gypsy is the highest, the deepest, the most genuine, and the greatest aristocrat of my country; also the guardian of the alphabet, the blood, and the marrow of the Andalucian truth”. Lorca is the poet of the myth, as Don Quixote calls it ‘the reason of the no reason’. He describes the conflict between the Gypsy’s eagerness to live without social restrictions, and the pressure society brings to bear on him. His freedom implies a return to a basic way of life. This “primitivism” springs from the very core of the earth; an encounter between popular and poetical sentiments. This common feeling is watered by blood: when blood flows it is the essence of life; once it is shed, it is the essence of death. This myth carries surrealist overtones, which came to Lorca through Dalí and Buñuel, at the time, his closest friends. “Primitivism” was to be full of human feeling, love, hatred, passion, memories, joy and pain. The poetical world of Lorca is based on an intense struggle. However, this violence does not stand alone, but is accompanied by eroticism. Lorca wrote in “Beautiful and the Wind”: The giant-wind chases her with a hot sword… And in “The Unfaithful Wife”: I touched her slumbering breasts and soon they blossomed for me… The theme of death also assumes a prominent place in Lorca’s lyricism. The poet manipulates his marionettes through a game of passion and death. Of the eighteen poems, thirteen end in pain, disillusion or death. The “Ballad of the Civil Guards” has the message of Picasso’s “Guernica”. Where did Lorca find his own inspiration?