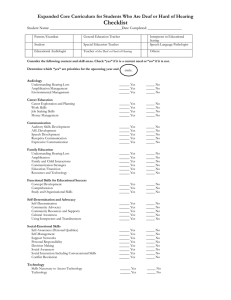

Deaf and Hard of Hearing Homeschoolers Sociocultural Motivation and Approach SIL International

advertisement