Self-Perceptions of speech language pathologists-in-training before and after

advertisement

DISABILITY AND REHABILITATION,

2003;

VOL.

25,

NO.

9, 491–496

CLINICAL COMMENTARY

Self-Perceptions of speech language

pathologists-in-training before and after

pseudostuttering experiences on the telephone

MANISH K. RAMI{*, JOSEPH KALINOWSKI{, ANDREW STUART{

and MICHAEL P. RASTATTER{

{ Stuttering Research Laboratory, Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders,

University of North Dakota, USA

{ Stuttering Research Laboratory, Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders,

East Carolina University, USA

Accepted for publication: January 2003

Abstract

Purpose: This survey investigated the effect of ‘pseudostuttering’ experiences on self-perceptions of 29 female, graduate

students enrolled in a graduate seminar in stuttering while in a

programme of study to become professional speech language

pathologists.

Method: Perceptions of self prior to, and immediately after,

participation in five scripted telephone calls that contained

pseudostuttering were measured via a 25-item semantic

differential scale.

Results: Participants perceived themselves as significantly more

(p 5 0.002) withdrawn, tense, avoiding, afraid, introverted,

nervous, self-conscious, anxious, quiet, inflexible, fearful, shy,

careless, hesitant, uncooperative, dull, passive, unpleasant,

insecure, unfriendly, guarded, and reticent after their pseudostuttering telephone call experiences.

Conclusions: Findings suggests that the pseudostuttering

experiences have an impact on self-perceptions and that the

experience of ‘adopting the disability of a person who stutters’

may provide insight as to the social and emotional impact of

communicative failure. It is suggested that pseudostuttering

exercises may be a valuable teaching tool for the graduate

students, especially for those who do not stutter.

Introduction

‘Pseudostuttering’ is defined as ‘the deliberate

production, by any speaker, of overt dysfluencies that

resembles stuttering . . .’ (p. 98).1 The pseudostuttering

experience is often used by those that treat the disor-

* Author for correspondence; e-mail: manish.rami@und.edu

der of stuttering.1 – 4 Pseudostuttering in the treatment

of stuttering has three purposes: to help the person

who stutters identify the overt core and ancillary

behaviours that are constituents of the stuttering

phenomena (e.g., repetitions, prolongations, facial

contortions, and head-jerking), to provide a series

of desensitization experiences which puts the oftreported ‘phobic’ stuttering experience into a different

perspective, and to demonstrate that stuttering is

comprised of both volitional and non-volitional

components.5

In addition to the aforementioned purposes, the practice of pseudostuttering also has a long history as a

teaching tool for speech language pathologists-in-training.1 – 4, 6 A multidimensional rationale for its use in

training includes: an efficient and effective way to illustrate the nature and difficulty of stuttering in environments where communicative failure bears some social

responsibility with its attendant costs (e.g., being

laughed at, uncomfortable stares, and deriving negative

social attention for aberrant behaviour). In other words,

some training institutions feel the best way to understand stuttering is to ‘embrace the disorder’ for short

periods of time and to use the ruse of ‘pretending’ to

be a person who stutters. Stuttering, unlike many other

disorders, is relatively easy to emulate and the disorder

bears no other signature behaviours other than stuttering itself, that would reveal the fallacious nature of the

pseudostuttering act. The use of pseudostuttering has

been recommended for speech language pathologists

and people who stutter to understand, empathize and

to test the reasonable and unreasonable expectations

Disability and Rehabilitation ISSN 0963–8288 print/ISSN 1464–5165 online # 2003 Taylor & Francis Ltd

http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals

DOI: 10.1080/0963828031000090425

M. K. Rami et al.

for fluency,3 and modelling stuttering for the sake of

analysis by the client.7 It has been suggested that pseudostuttering be used to help improve the speech

language pathologist’s understanding of the attitudes

toward stuttering population and their attendant skills

in dealing with the disorder.1 Several researchers have

indicated its use for desensitization in the stuttering

population, transfer and maintenance; 4 – 6, 8 – 10 and in

the training of prospective speech language pathologists.1, 3, 4 The practice of having speech language pathologists-in-training

experience

stuttering

via

pseudostuttering exercises has been in existence since

the mid 1930’s and it continues to be in use.1 – 10

Several authors have reported that reluctance, anxiety, and resistance to pseudostuttering among normal

speakers is common.1, 5, 8, 11, 12 Ratings of self-perception

of ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ ‘beauty’ before and after pseudostuttering assignments of 55 students were examined

by Klinger.12 A significant lowering of perceptions of

inner and outer ‘beauty’ after pseudostuttering experiences was reported. Students were instructed in the act

of pseudostuttering and asked to initiate a series of pseudostuttering interactions off-campus. This assignment

was completed without supervision or monitoring.

From changes noted in inner and outer beauty, the

author inferred that the pseudostuttering experience

was capable of lowering self-image and producing empathy for people who stutter. However, Klinger failed to

identify the possible origin of this effect and to specify

how changes in beauty translated into possible changes

in perceptions of character traits or perceptions of self.

Given the above findings,12 the oft-stated student

apprehensions about the pseudostuttering assignments,1, 4, 5, 8 and on the basis of anecdotal evidence,11

one may expect some change in self-perceptions of

normal speakers and people who stutter due to pseudostuttering experiences. If these pseudostuttering exercises

are to be employed with any knowledge of benefit, it

seems essential to empirically demonstrate if any change

occurs as a result of these exercises. If changes do occur,

then we need to determine the pattern of that change in

self-perceptions as a result of pseudostuttering exercises.

However, no empirical evidence of the effects of these

exercises on the short- and long-term self-perceptions

and perceptions towards people who stutter is currently

available. This study examined the immediate effect of

pseudostuttering experience during scripted telephone

calls on the self-perception of speech language pathologists-in-training. Telephone calls were used to make the

experience somewhat distant as compared to a face-toface experience, which participants have shown resistance to enter into.1, 4, 5, 8, 12

492

If the pseudostuttering experience is as powerful as

anecdotally, and otherwise reported, one would expect

a substantial shift in self-perceptions, which would indicate the cognitive/affective power of stuttering (be it of

the artificial kind or be it real.) However, if the act of

stuttering itself is not a genesis of these percepts, then

no shift should occur.

Methods

PARTICIPANTS

Twenty-nine graduate female students, enrolled in a

graduate course in Stuttering and other Fluency Disorders and in training to become professional speech

language pathologists at East Carolina University,

served as participants in this study. Their mean age

was 23.5 years (SD = 1.5). All participants were volunteers and reported normal speech, language, and hearing. An all female sample is considered appropriate

since over 95.2% of practicing speech language pathologists are females.13 In addition, rater gender has not been

found to be a significant factor.14

MATERIALS

A scale of 25 traits consisted of adjectives which

speech language pathologists most frequently used to

describe people who stutter.14 These words were paired

with antonyms to form a bipolar dimension with a 7point Likert scale. Numerous researchers15 – 21 have

employed this scale and it has been used to survey

self-perceptions and stereotypes towards people who

stutter and others as well as to quantify the effect of a

specific experience22 (watching a video tape) in normally

speaking people on their perceptions towards selves and

people who stutter. This 25 item semantic differential

survey was administered to examine the self-perceptions

of the participants in this experiment.

Forty telephone call scripts were used in this experiment. Twenty-one scripts for telephone calls were developed and used along with nineteen available scripts.23

See Appendix A for the telephone scripts.

PROCEDURE

University and Medical Center’s Institutional Review

Board at East Carolina University, Greenville, NC,

approved this experimental study. The first author

conducted all testing. Participants individually met with

the experimenter, in a quiet laboratory setting to participate in this experiment. All participants were volunteers,

and written informed consents were obtained from the

Effect of pseudostuttering on self-perceptions

participants before beginning the experiment. The 25item scale was administered prior to and following the

pseudostuttering telephone calls. All participants were

instructed to evaluate how they felt about themselves

at the present time. See Appendix B for instruction.

Participants were instructed that they would be making

five scripted telephone calls to local businesses while

voluntarily stuttering during their conversation.

Stuttering was operationally defined for all participants as ‘Part-word or whole word, repetitions and/or

prolongations and/or postural fixations or blocks’.

These defined behaviours were demonstrated for each

participant individually by the first author, an experienced speech language pathologist, and all participants

were given an opportunity to rehearse each of the

defined stuttering behaviours for several minutes before

making the telephone calls. Participants were provided

with an opportunity to ask questions and clarify if they

had any doubts. The individual participant’s ability to

produce stuttering like behaviour was not a concern

since it is shown that listeners do not differentiate

between real stuttering and pseudostuttering.24

However, all telephone conversations were audio

recorded, and 30 telephone calls (20%) were randomly

selected and analysed for number of syllables stuttered

by the participants. The mean number of syllables stuttered were found to be 23.3% (range 12 – 46%.) It has

been shown that speech language pathologists rate all

levels of stuttering severity negatively as compared to

normals.16 Participants were instructed not to deviate

from the script but they were allowed to ad lib briefly

to keep the conversation as natural as possible. Specific

instructions as to where exactly to pseudostutter in the

given script were not given to participants. Telephone

scripts were randomly selected from the list of scripts

and telephone numbers of target businesses were

randomly chosen from the Yellow Pages in the local

telephone book. Five scripted telephone calls were made

successively in presence of the experimenter and upon

completion of the calls, the participants were asked to

rate their self-perceptions during and immediately after

these telephone calls.

telephone call ratings of self perceptions. Comparison

of the pre- and post-telephone call ratings of self-perceptions were of specific interest. Table 1 shows the results

of the Wilcoxon matched pairs sign rank tests for the 25

items revealing that significant difference existed for 22

items (p 5 0.05).

RESULTS

Discussion

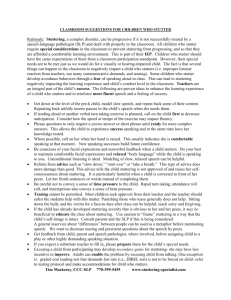

Figure 1 illustrates the mean and standard error

values for the 25 items on semantic differential14 for

the pre- and post- pseudostuttering telephone calls of

all the participants. Wilcoxon matched pairs sign ranks

tests were conducted to explore differences between

Likert scores of all the 25 attributes in the semantic

differential scale for the pre- and post-pseudostuttering

The principal finding of this study is that a negative

self-perception emerged following the experimental

condition of a series of pseudostuttering telephone

calls in speech language pathologists-in-training. Specifically, the results showed a significant shift in 22 of

the 25 scales (p 5 0.05). After the telephone calls,

speech language pathologists-in-training were signifi-

Figure 1 Pre- and post-pseudostuttering telephone calls

mean Likert scale scores for all 25 attributes. Open circles

represent pre-pseudostuttering telephone call ratings and

closed circles represent post-pseudostuttering telephone call

ratings. Error bars represent plus minus one standard error.

Asterisks on the ordinate scale item pairs represent statistical

significance.

493

M. K. Rami et al.

Table 1 Summary table for Wilcoxon matched pairs sign rank tests

between pre- and post-pseudostuttering telephone calls for each scale

item.

Statistics

Pairs

*Withdrawn – Outgoing

*Tense – Relaxed

*Avoiding – Approaching

*Afraid – Confident

*Introverted – Extroverted

*Nervous – Calm

*Self-conscious – Self-assured

*Anxious – Composed

*Quiet – Loud

*Inflexible – Flexible

*Fearful – Fearless

*Shy – Bold

Sincere – Insincere

Bragging – Self-derogatory

Emotional – Bland

*Perfectionistic – Careless

*Daring – Hesitant

*Cooperative – Uncooperative

*Intelligent – Dull

*Aggressive – Passive

*Pleasant – Unpleasant

*Secure – Insecure

*Friendly – Unfriendly

*Open – Guarded

*Talkative – Reticent

z

p

7 4.12

7 3.79b

7 3.54b

7 3.18b

7 3.64b

7 3.34b

7 3.30b

7 3.18b

7 3.93b

7 3.44b

7 2.66b

7 2.70b

7 0.35b

7 0.16b

7 0.11a

7 2.33a

7 2.94a

7 2.95a

7 3.82a

7 3.80a

7 3.49a

7 3.45a

7 4.05a

7 4.27a

7 4.12a

b

0.001

5 0.00

5 0.00

0.001

5 0.00

0.001

0.001

0.001

5 0.00

0.001

0.008

0.007

0.726

0.869

0.906

0.02

0.003

0.003

5 0.00

5 0.00

5 0.00

0.001

5 0.00

5 0.0

5 0.00

(Note: *considered significant at p 5 0.05, a = based on negative

ranks, b = based on positive ranks.)

cantly more withdrawn, tense, avoiding, afraid, introverted, nervous, self-conscious, anxious, quiet, inflexible, hesitant, dull, passive, unpleasant, insecure,

unfriendly, guarded, and reticent. This shift, towards

more negative percepts, suggests that perception of

self can be altered via the voluntary pseudostuttering

experience.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first experiment to show that normal speaking graduate speech

language pathologists-in-training can, at least for a time,

‘stand in the shoes’ of the person who stutters. That is,

after the pseudostuttering experience and the communicative disruption during a series of telephone calls to

various businesses, normal speakers evoked a statistically significant negative shift in perception indicating

a strong emotional response.

Nothing exemplified the power of this act more

than the emotional responses of some of the participants, although most stated they were grateful for

the insight and knowledge they gained from the stuttering experience, they often responded with affective

distress. At times, participants would show a flushed

face and neck before calling, breathe heavily, post494

pone, avoid calling the telephone number, and some

would even well-up in tears—but when asked if they

would like to stop, they would ask to continue. There

were also comments such as ‘this was one of the most

difficult things I did in my life’, ‘I would hate to do

this all the time’ and so on. Thus, it is evident that

the teaching tool of pseudostuttering does succeed in

furnishing the students with a powerful experience.

Further, the results also suggest that stuttering is so

salient and vivid that one seemingly reacts to

controlled, voluntary, and short-lived stuttering in

the same manner as those who demonstrate a chronic

pathology.

The question as to the value of this commonly

employed exercise remains. One can speculate that there

can be a positive and a negative outcome. On the positive side, this exercise can provide the students in training with an experience to develop empathy towards

people who stutter. They viewed life on life’s terms as

a person who stutters does for a short period of time,

and it was disconcerting, uncomfortable, and eye opening. This experiential face with stuttering is one that

cannot be taught in a didactic fashion, but must be felt

viscerally and emotionally and will change how the

speech pathologist views the disorder and the person

who stutters. On the negative side, a caveat must be

expressed that such an experience could confirm the

negative stereotype held by the normal speaking population towards people who stutter,22, 25 which is not

substantiated by the personality literature.26 However,

the incongruence between the stereotype and reality of

personality changes may finally be just a simple manifestation of the saliency and vividness of the powerful,

aberrant, atypical nature of the stuttering moment.

Thus, one may have the first empirical inkling into the

lack of congruency between what people who stutter feel

and what others feel about them. Stuttering, even

pretend stuttering, is very powerful.

References

1 Ham R. Techniques of Stuttering Therapy. Englewood Cliffs, New

Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1986.

2 Bryngelson B. Sidedness as an etiological factor is stuttering.

Journal of Genetic Psychology 1935; 47: 205 – 217.

3 Mulder RL. The student of stuttering as a stutterer. Journal of

Speech and Hearing Disorders 1961; 26: 178 – 179.

4 Ham R. Therapy of Stuttering, Preschool Through Adolescence.

Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1990.

5 Van Riper C. The Treatment of Stuttering. Englewood Cliffs, New

Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1973.

6 Shapiro DA. Stuttering Intervention: A collaborative journey to

fluency freedom. Austin, Texas: Pro-ed, 1999.

Effect of pseudostuttering on self-perceptions

7 Maxwell DL. Cognitive and behavioral self-control strategies:

application for the clinical management of adult stutterer. Journal

of Fluency Disorders 1982; 7: 403 – 432.

8 Van Riper C. Experiments in stuttering therapy. In: J Eisenson

(ed). Stuttering: A symposium. New York: Harper & Row, 1958;

273 – 392.

9 Adler S. A Clinician’s Guide to Stuttering. Springfield, Illinois:

Charles C. Thomas, 1966.

10 Gregory H. Controversies About Stuttering Therapy. Baltimore,

Maryland: University Park Press, 1979.

11 Woods CL. Stigma of a disorder. Australian Journal of Human

Disorders of Communication 1976; 4: 133 – 139.

12 Klinger H. Effects of pseudostuttering on normal speakers’ selfratings of beauty. Journal of Communication Disorders 1987; 20:

353 – 358.

13 American Speech–Language–Hearing Association. Asha count for

mid-year 2002. Rockville, MD: Author, 2002.

14 Woods CL, Williams DE. Traits attributed to stuttering and

normally fluent males. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research

1976; 19: 267 – 278.

15 Yairi E, Williams DE. Speech clinicians’ stereotypes of elementaryschool boys who stutter. Journal of Communication Disorders 1970;

3: 161 – 170.

16 Turnbaugh KR, Guitar BE, Hoffman PR. Speech clinicians’

attribution of personality traits as a function of stuttering severity.

Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 1979; 22: 37 – 45.

17 Turnbaugh KR, Guitar BE, Hoffman PR. The attribution of

personality traits: the stutterer and nonstutterer. Journal of Speech

and Hearing Research 1981; 24: 288 – 291.

18 White PA, Collins SRC. Stereotype formation by inference: A

possible explanation for the ‘stutterer’ stereotype. Journal of Speech

and Hearing Research 1984; 27: 567 – 570.

19 Kalinowski JS, Lerman JW, Watt J. A preliminary examination of

the perceptions of self and others in stutterers and nonstutterers.

Journal of Fluency Disorders 1987; 12: 317 – 331.

20 Kalinowski J, Armson J, Stuart A, Lerman J. Speech clinicians’

and the general public’s perception of self and stutterers. Journal of

Speech–Language–Pathology and Audiology 1993; 17: 79 – 85.

21 Kalinowski J, Stuart A, Armson J. Perception of stutterers and

nonstutterers during speaking and nonspeaking situations. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 1996; 5: 61 – 69.

22 McGee L, Kalinowski J, Stuart A. Effect of a videotape

documentary on high school students’ perceptions of a high school

male who stutters. Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 1996;

20(4): 240 – 246.

23 Zimmerman S, Kalinowski J, Stuart A, Rastatter MP. Effect of

altered auditory feedback on people who stutter during scripted

telephone conversations. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing

Research 1997; 40: 1130 – 1134.

24 Fucci D, Leach E, Mckenzie J, Gonzales MD. Comparison of

listeners’ judgments of simulated and authentic stuttering using

magnitude estimation scaling. Perceptual and Motor Skills 1988;

87: 1103 – 6.

25 Leahy MM. Attempting to ameliorate student therapists’ negative

stereotype of the stutterer. European Journal of Disorders of

Communication 1994; 29(1): 39 – 49.

26 Bloodstein O. A Handbook of Stuttering. San Diego, California:

Singular Publishing, 1995.

Appendix A

LIST OF TELEPHONE CALL SCRIPTS

1 Restaurant: Hello, I am calling to see if you have a

Sunday brunch. What does it include? Do you have children’s menu? Thank You.

2 Department Store: Hello, Could I have the jewelry

department please? Do you have any Timex watches?

What time do you close today? Thank You.

3 Office Supply: Hello, Do you sell mouse pads for a

computer? Where are you located? What time do you

close? Thank You.

4 Sporting Goods: Hello, Do you carry rollerblades?

And do you also carry snowboards? Are you open on

Friday night? Thank You.

5 Hotel: Hello, Do you have a conference room to

accommodate a party of 10? Do you cater? Do you have

a lounge in your facility? Thank You.

6 Bakery: Hello, Do you make birthday cakes? How

many days’ notice would you require? Do you take Visa

or Mastercard? Thank You.

7 Hotel: Hello, What is your rate for a double room?

Do you have a fitness centre? Do you have a swimming

pool? Thank You.

8 Copy Centre: Hello, Do you make colored overheads? What is your charge per overhead? What time

do you open weekday mornings? Thank You.

9 Dry Cleaner: Hello, How much do you charge to dry

clean a man’s sport jacket? If I drop it off in the morning, may I pick it up the same day? Are you open on

Sundays? Thank You.

10 Video Store: Hello, Can you tell me if you have the

movie ‘‘Chasing Amy’’? What are your membership

requirements? Thank You.

11 Bookstore: Hello, I was wondering if you have the

new book by John Grisham in stock? Is that hard or soft

cover? How much is it? Thank You.

12 Florist: Hello, Can you tell me how much your

long-stem roses are per dozen? How much are a dozen

carnations? Do you take Mastercard? Thank You.

13 Hair Salon: Hello, How much do you charge for a

man’s shampoo, cut, and blow dry? Do I have to make

an appointment? Thank You.

14 Pet Store: Hello, I am interested to know if you

carry rabbit food? What brands do you carry? Do you

sell chew toys? Thank You.

15 Toy Store: Hello, Do you carry the ‘Tickle me

Elmo’ doll? Do you have them in stock? Can you tell

me where your store is located? Thank You.

16 Music Store: Hello, Do you carry CD’s by the

band ‘Ben Folds Five’? Do you know if you have all

three of their albums in stock? Can you tell me when

you close tonight? Thank You.

495

M. K. Rami et al.

17 Audio Store: Hello, Does your store sell tube

amplifiers? Can you tell me if you sell Polk Audio? What

time will you be closing tonight? Thank You.

18 Restaurant: Hello, Do you serve Chicken Parmesan? Can you tell me where you are located? Does your

restaurant deliver? Thank You.

19 Shoe Store: Hello, Do you have a big selection of

work boots? I wear a size 15; do you have work boots

in my size? Do you carry children’s shoes as well? Thank

You.

20 Garden Supply: Hello, What is your price for a 10lb. bag of potting soil? Do you have any geraniums?

How late are you open today? Thank You.

21 Bank: Hello, Do you have safety deposit boxes?

What sizes do you have? What is the rent for your smallest safety deposit box? Thank You.

22 Library: Hello, What kind of ID do I need to get a

library card? Is there a charge for that? What are your

hours on the weekend? Thank You.

23 Carpet Cleaner: Hello, What is your charge to

steam clean a 12 6 14 room? When could I make an

appointment to have that done? Do you take American

Express? Thank You.

24 Bowling Alley: Hello, How late are you open

tonight? What is your charge per game? How much

are your shoe rentals? Thank You.

25 Car Wash: Hello, How much do you charge to

wash and wax a compact car? Do I need to make an

appointment to have that done? Are you open on Saturdays? Thank You.

26 Golf Store: Hello, Do you carry Titleist DCI irons?

Do you have any in stock right now? How late are you

open on the weekends? Thank You.

27 Camera: Hello, Do you have one hour photo

processing? How much do you charge to develop a roll

with 24 exposures? What time do you close today?

Thank You.

28 Computer Games: Hello, Do you carry the game

‘‘Myst’’? Do you have it in stock? Where are you

located? Thank You.

29 Pharmacy: Hello, What are your pharmacy hours

on the weekend? Can I call in prescriptions ahead of

time? Will you be able to file my prescriptions on my

insurance for me? Thank You.

30 Vet: Hello, How much do you charge to groom a

Standard Poodle? How long will I need to leave my

dog to have that done? Are you open on the weekends?

Thank You.

31 Church: Hello, What time are your Sunday

services? Do you also have Sunday school classes? Is

there a nursery available on Sundays? Thank You.

496

32 Coffee Shop: Hello, How much do you charge for a

dozen-glazed doughnuts? Do you also sell sandwiches or

bagels? What time do you open in the morning? Thank

You.

33 Motel: Hello, I was wondering if you had any

vacancies for next Thursday through Sunday? Do I need

a credit card to reserve a room? Does your hotel offer

free movie channels? Thank You.

34 Camera Store: Hello, I was wondering if you sold

lenses for the Canon Eos? Do you also carry lithium

batteries that fit this camera? How late are you open

tonight? Thank You.

35 Bicycle Store: Hello, I was wondering if you sold

Schwinn Bicycles? Does your store carry a large selection of rims? Are you open on Sundays? Thank You.

36 Car Rentals: Hello, What kind of cars does your

store rent? How much is the insurance that your store

offers if I rent a car? Do your cars come with unlimited

mileage? Thank You.

37 Moving Van Rental: Hello, What are the sizes of

the moving vans that you carry? How much does your

company charge per-mile? Can you tell me how much

it costs to rent a hand-truck? Thank You.

38 Pizza Joint: Hello, How many people will a large pizza

serve? I was wondering if your restaurant made Chicago

Style pizzas? Does your store deliver? Thank You.

39 Grocery Store: Hello, Is your store hiring employees? What qualifications do I need to work at your store?

How much money do new employees make? Thank

You.

40 Electronic repair store: Hello, I think my VCR has

a tape stuck in it, how much would it cost for you to

take a look at it? How long will it take to fix it? Can

you tell me when you close tonight? Thank You.

Appendix B

INSTRUCTIONS

The following were the instructions for completing the

25-item scale (Woods & Williams, 1976):

Below you will see some rating scales each with seven

points. We would like you to evaluate how you feel

about YOURSELF AT THE PRESENT TIME on each

of these scales. Please circle the number on the scale that

best describes your current feelings about YOURSELF,

on each scale.