Transnational Dispute Management www.transnational-dispute-management.com

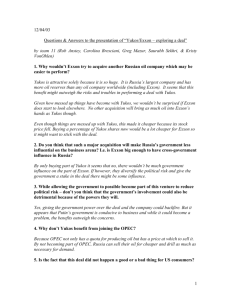

advertisement