Proceedings of International Social Sciences and Business Research Conference

advertisement

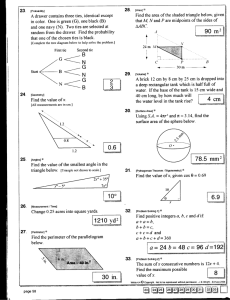

Proceedings of International Social Sciences and Business Research Conference 4 - 5 December 2014, Hotel Himalaya, Kathmandu, Nepal, ISBN: 978-1-922069-65-8 The Paradoxes of Economic Optimism in Russia: Social Capital and Social Ties Strength Influence Victor Vakhshtayn and Pavel Stepantcov1 The main aim of our report is to reveal factors of economic optimism in Russia. This report is based on data received during the research «Evrobarometr in Russia», conducted 2 times per year since November, 2012. Sample size - 6000 people. This survey is carried in 10 Russian regions, in each of them 600 people are questioned. Received data is valid and representative for Russia generally and for each region as well.While the real incomes of population reduced, economic expectations of Russians increased on 20%, as data showed. This paradox couldn’t be explained neither by economic situation improvement in the country (estimation of current economic situation is worse than it was during the previous year study), nor by security of Russian citizens in economic institutions functioning. More than 50% of Russians doesn’t trust to governmental institutions responsible for economics operation, including pension funds and banks. As data analysis showed the main reason of economic optimism in these conditions is increase of respondents' social capital. By the moment social capital is the main source for insurance of their own economic future. Along this the integral parts of social capital - strong and weak ties accomplish their functions differently. The weak ties provide sense of confidence by means of social networks diversification and by reducing of the risks on the labor market in the first place. At the same time strong ties provide more fundamental safety feeling, which is expressed in confidence that respondents will receive help from close friends and relatives. In the basis of sense of safety is not diversification but strength of contacts which is used, however, only in extreme cases. These and other questions will be examined more explicitly in our report. Field of Research: Sociological Theory 1. Introduction Social capital, as the results of the “Eurobarometer in Russia” research project have shown, is one of the main resources that underpin the socio-economic wellbeing of Russians. The quantity and contact intensity of social ties are micro-level determinants for the patterns of economic behaviour, financial strategies and career paths of Russians. It remains unclear, however, how Russians convert social capital into real economic resources. In this research paper, we propose to study the mechanisms of “cashing in” social relations, revealing the most prevalent strategies for converting social capital to economic capital. Additionally, we aim to determine the socio-economic obstacles that hinder the accumulation of said social capital. The methodology for studying the practices and strategies of the population’s economic behaviour was developed based on the Europe-wide research project “Eurobarometer”. 1 Victor Vakhshtayn – Director, Centre for Sociological Research, The Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, avigdor2@yahoo.com; Pavel Stepantcov –Leading Research Fellow, Centre for Sociological Research, The Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, pavel.stepantsov@gmail.com 1 Proceedings of International Social Sciences and Business Research Conference 4 - 5 December 2014, Hotel Himalaya, Kathmandu, Nepal, ISBN: 978-1-922069-65-8 2. Methodology The “Eurobarometer in Russia” research project had a sample size of 6,000 people. The survey was conducted in ten constituent regions of the Russian Federation, with 600 people polled per region. The sample has a threefold representativeness: - It reflects the overall structure of the population in the constituent region; - It corresponds to the level of socio-economic development of the respective constituent region; - It is representative of the Russian Federation as a whole; The questionnaire of the “Flash Eurobarometer” is divided into five sections and totals 85 questions. In addition to the sections on the economy and life satisfaction from the preceding years’ questionnaire, which is combined for this year’s questionnaire, four new sections have been added. The new sections correspond to the four important and widely discussed themes within the public and political domains: workplace relations, taxation, further education and migration. Within each section, the population’s values and actual practices were evaluated. The economic and life satisfaction section contains questions regarding the economic behaviour, attitudes and risk-taking tendencies of the population, as well as questions about expectations and practices within the economic sphere. Furthermore, the section touches upon the general question of happiness and its correlation and dependence on events in the population’s economic life. The workplace relations section consists of questions that measure the peculiarities of workplace relationships and behaviour. Specifically, there are questions regarding recruitment and change of occupation practices, satisfaction with working conditions and wages, the perceived likelihood of losing one’s job and the likelihood of finding new employment. The taxation section evaluates the peculiarities of tax relations, the behaviour of Russians in the sphere of taxation, their willingness to pay taxes when they change (including tax increases) as well as their preferences concerning budget expenditures. The section on further education gives an overview over the population’s attitudes towards advanced vocational training, draws attention to the existing hurdles and incentives and assesses the perceived usefulness of the obtained education. Finally, the migration section includes questions on migration practices, motivations, reasons and trajectories. 3. Paradoxes of economic optimism It is traditionally assumed that levels of optimism are closely correlated with objective levels of wellbeing, as well as with the general assessment of the economic situation 2 Proceedings of International Social Sciences and Business Research Conference 4 - 5 December 2014, Hotel Himalaya, Kathmandu, Nepal, ISBN: 978-1-922069-65-8 in the country. Income growth and favourable socio-economic conditions allow the public to make optimistic predictions about their future. This trend is confirmed by the findings of a Eurobarometer research conducted in the European Union in 2014. The proportion of Europeans that positively assess the economic situation in their country and in Europe as a whole has risen by 3 percent in comparison to the previous year; while the number of people that think that the economic situation is worsening has decreased by 7 percent for the respective country and 9 percent for Europe in total. It appears that an increasingly positive assessment of the situation in one’s country leads to the increasingly positive assessment of one’s own future: the amount of Europeans that assume that the next year, for them, will be better than the last has risen by 2 percent in the last year, while the number of pessimists has decreased by 5 percent. However, as the analysis of data obtained during the “Eurobarometer in Russia” research indicates, Russian optimism seems to function differently: it does not depend on an objective increase in wellbeing or an assessment of the country’s economic situation in general. For instance, the economic situation has not changed for the better. The real income of Russians has stagnated. According to the latest data of the Federal State Statistic Service published in September 2014, the per capita income amounted to 108,6 percent in comparison to 2013, though the real income of Russians, adjusted for inflation and excluding mandatory payments, has risen by a mere 0.6 percent relative to last year – and has actually fallen slightly in comparison to August. As can be seen from the above, no real income growth can be observed; nevertheless, the number of optimists in Russia is growing: compared to 2012, the economic optimism index has risen by more than 20 points. The absolute majority of Russians (55.8 percent) believe that 2015 will be better for them than the last year; 30.6 percent believe that it will be the same; and only 13.6 percent believe that the next year will turn out to be worse for them. The level of optimism in Russia is higher than in most European countries, as well as the United States. In the United Kingdom, 42 percent of the population have an optimistic outlook on the future, in Italy it is 35 percent, in Germany, 30 percent; and the quantity of optimists in the US in 2014 did not exceed 48 percent. The economic optimism index represents the difference between favourably disposed people (i.e. those who think that next year will be better, in terms of the economic situation) and negatively disposed people (i.e. next year will be worse). While the median income level declined by 10 percent in the recent years, economic optimism, conversely, increased by 10 percent in the same timeframe. 3 Proceedings of International Social Sciences and Business Research Conference 4 - 5 December 2014, Hotel Himalaya, Kathmandu, Nepal, ISBN: 978-1-922069-65-8 Figure 1: The correlation between median income level and economic optimism 50 45 40 35 30 The median income (thousands rub) 25 Economic optimism 20 15 10 5 0 2012 2013 2014 Economic optimism does not depend on personal income, either. One of the “happiest” Russian constitutive regions in terms of economic optimism is the Republic of Dagestan. However, its median monthly household income is the lowest in Russia. Moscow – the leader in median income – on the other hand, is bottom third in terms of economic optimism. In general, Russians tend to have a positive outlook on the future, regardless of the actual income level. 4 Proceedings of International Social Sciences and Business Research Conference 4 - 5 December 2014, Hotel Himalaya, Kathmandu, Nepal, ISBN: 978-1-922069-65-8 Figure 2. What are your expectations for the year 2015 – for you personally it will be: 70.0% 60.0% 50.0% 40.0% 30.0% Situation will be better 20.0% Situation will be the same 10.0% Situation will be tworse 0.0% As can be seen in the above graph, the number of people expecting improvement in the coming year is not determined by the level of real income. Rather, the distribution of optimists and pessimists is about the same in all categories. Moreover, in the group of people whose income does not exceed 5,000 roubles, the percentage of optimists is above the national average; while among people with incomes of more than 50,000 roubles there are more pessimists than in the group earning less than 20,000. Russian optimism levels, unlike the Europeans’, do not depend on the subjective assessment of the economic situation in the country: 43 percent of Russians believe that over the past 12 months, the economic situation in the country has worsened (only 26 percent believe otherwise), but this does not stifle their optimism. Furthermore, optimism regarding one’s own future is independent not only from the evaluation of the current state of the economy but also from the expected economic situation in the coming year. Specifically, almost a half of the Russian population (49 percent) believes that prices will rise increase more rapidly than in this year – only 6 percent hope for a decreasing rate of inflation. This is confirmed by the data of the Federal State Statistic Service that shows that the “consumer confidence index”, an index that reflects the aggregate consumer expectations of the population, had dropped by one point in the third quarter of 2014 and currently stands at 7 percent. Thus, Russians do not believe in a coming general improvement of the economic situation. At the same time, they expect that – for them, personally – next year will be better than the previous one. 5 Proceedings of International Social Sciences and Business Research Conference 4 - 5 December 2014, Hotel Himalaya, Kathmandu, Nepal, ISBN: 978-1-922069-65-8 The explanation for this phenomenon is provided by an investigation into “happiness”. For Russians, economic optimism does not hinge upon their real financial situation but on the level of happiness. The happier a resident of Russia feels to be, the higher the tendency is to positively evaluate his or her own prospects. Among those who consider themselves “very happy”, the rate of those who think next year will be better than the last one is 70 percent; among those who are “mostly happy”, the rate is 54 percent; for those who are “mostly unhappy” the rate is 34 percent; and among those who are “very unhappy”, the portion of people with a positive outlook is a mere 27 percent. Happiness is wholly unrelated to factual financial wellbeing. For instance, the number of “very happy” people earning no more than 5,000 roubles is only 2 percent lower than in the group earning more than 150,000 roubles per month. However, while there is no link between happiness and income levels, happiness is tied to the subjective evaluation of one’s wellbeing. A third of all Russians that deem their financial standing to be better off than their friends and acquaintances also consider themselves “very happy”. Among those people who believe that the financial standing of their family is worse off than that of their surroundings, only 16 percent consider themselves to be “very happy”. People who think themselves to be better off than their acquaintances have almost ten times fewer “very unhappy” people than those that consider themselves poorer than their surroundings. Figure 3. In your opinion, are you: very happy, mostly happy, mostly unhappy, very unhappy? 80.0% 70.0% 60.0% 50.0% Very happy 40.0% Happy 30.0% Unhappy Very unhappy 20.0% 10.0% 0.0% Financial situation is Financial situation is the Financial situation is better that friends have same that friends have worse that friends have Thus, Russians have a positive outlook on their own future, despite the slowing growth of income, poor assessments of the current economic situation and rather poor expectations regarding the future economic development of the country as a 6 Proceedings of International Social Sciences and Business Research Conference 4 - 5 December 2014, Hotel Himalaya, Kathmandu, Nepal, ISBN: 978-1-922069-65-8 whole. The determining factors of Russian optimism are the levels of happiness and the subjective assessment of one’s wellbeing. 4. Optimism and social capital The Happy Planet Index (HPI), proposed by the New Economics Foundation, is based on the study of the real state of national wellbeing. The HPI uses a number of objective indicators, such as average life expectancy and environmental conditions in addition to purely subjective evaluations. Presumably, favourable living conditions and healthy surroundings make people happier. According to the HPI, Russia’s place in the ranking is beyond the first hundred positions. However, research that evaluates happiness based on subjective estimates of life satisfaction shows that the level of life satisfaction of Russians is quite high. The “happiness index” used in the context of the Eurobarometer is compiled based on the sum of the subjective evaluation of personal happiness and the subjective evaluation of life satisfaction. The collected data of the recent years shows that the happiness index is progressively increasing. This trend is confirmed by other studies. According to the survey regularly conducted by Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VTsIOM), the happiness index has reached a 25-year high in 2014. Subjective assessment of personal happiness is not linked to objective financial wellbeing. The assessment of personal happiness is virtually unrelated to the level of income. For example, while 25 percent of Russians are “very happy”, 67 percent are “mostly happy”, 7 percent are “mostly unhappy” and only a little over 1 percent of think that they are “very unhappy”, the lowest income category has eight percent more “very happy” people than the national average. The lack of connection between happiness and the objective economic conditions is further enforced by the distribution level of happiness in the constitutive regions: Moscow turned out to be one of the least happy regions. The happiest people reside in Dagestan (the region with the lowest level of income in the current sample); the second place in the list of happiest regions is taken by Tatarstan. The level of happiness is not connected to age or sex; happiness is also unrelated to the assessment of the economic and political situation in the country. The proportion of happy people among those who think that the political situation in the country has improved and differs only by 2 percent from those who think it has worsened. As the “Eurobarometer in Russia” research data has shown, the main factor influencing the happiness index is social capital or the number of social ties. A decisive role is played by the so-called “weak social ties”, that is, the number of acquaintances and friends. 5. Strong and weak ties There are two types of social relations: weak and strong ties. Formally, one can distinguish between these two types by the frequency and duration of contact. 7 Proceedings of International Social Sciences and Business Research Conference 4 - 5 December 2014, Hotel Himalaya, Kathmandu, Nepal, ISBN: 978-1-922069-65-8 An example of strong ties would be relatives and close friends; these links are of lasting a duration and have an intimately personal nature. Strong ties play a special role for the individual, while the extent of such ties is seen as an integral element of wellbeing and, consequently, happiness. In times of need, people would most likely turn to those with whom they have established strong ties. Strong ties form the backbone of social capital. Weak ties are those links that are less intimate and may be of a shorter duration. For example, neighbours, acquaintances, formal contacts at work and in everyday life can be considered weak ties. In difficult circumstances, people expect help from those with whom they are linked by weak ties (e.g., when it comes to job hunting). This is explained by the fact that strong ties are informationally redundant. Mark Granovetter explained this phenomenon by pointing out that relatives and close friends know one another and therefore transmit the same information. Acquaintances, on the other hand, are dispersed across different social circles and not interconnected. They thereby give a person access to diverse sources of information and social spheres. This is Granovetter’s thesis of “the strength of weak ties”. 6. The dependence of happiness on the number of social ties With an increasing number of social ties, the percentage of “very happy” people rises, while the number of “mostly unhappy” and “very unhappy” people declines. If one compares people whose contact list has more than one hundred phone numbers with people who have no more than ten, we see double the number of “very happy” people in the first group, as well as six times less people who are “very unhappy”. Figure 4. In your opinion, are you: very happy, mostly happy, mostly unhappy, very unhappy? 80.0% 70.0% 60.0% 50.0% Very happy 40.0% Happy 30.0% Unhappy 20.0% Very unhappy 10.0% 0.0% Less 10 25 than 10 26-50 51-100 101-200 More than 200 If we look at the regional distribution of social capital, we see that people from Dagestan are the most communicative: 21 percent of Dagestanis have no less than two hundred acquaintances (compared to the 10 percent national average), while 20 percent have more than one hundred (which is also double the national average 8 Proceedings of International Social Sciences and Business Research Conference 4 - 5 December 2014, Hotel Himalaya, Kathmandu, Nepal, ISBN: 978-1-922069-65-8 figures). This explains the consistently high level of happiness among the inhabitants of that constituent region. Why does the amount of social ties more accurately determine the level of happiness than objective wellbeing? Weak ties provide a sense of security. Russians are not certain that the state of the economy will develop in a favourable fashion. However, they assume that having a large circle of contacts ensures that they will be able to tackle problems - including those of an economic nature – by using their social capital in order to, for example, find work or borrow money. Socially active people in particular – i.e. those who have no less than 100 contacts – have a twice as high frequency of borrowing money from acquaintances than people with a narrower social circle. Figure 5. In the event of an emergency (urgent need to repay the loan for an apartment or a car, pay for expensive surgery, etc.), how much money would you be able to collect within three days? More than 200 101-200 51-100 26-50 10 25 Less than 10 0 20000 40000 60000 80000 100000 120000 As the diagram shows, the amount of money a person could collect in times of need is directly related to the amount of social ties the person possesses: people who have no more than 25 acquaintances, the median sum is amounts to 15,000 roubles. This sum increases with the number of social ties: if the number of contacts a person has exceeds 50 people, he or she can expect to collect a sum of 50,000 roubles within three days. If he or she has more than 200 acquaintances, the median available sum is 100,000 roubles. Thus, diversity of contacts minimizes economic risks, creates a sense of safety, contributes to confidence about tomorrow and promotes a general feeling of happiness. This is why, despite the rather pessimistic assessment of the country’s economy, a large circle of acquaintances allows for a more optimistic assessment of a person’s own prospects in the given situation. 9 Proceedings of International Social Sciences and Business Research Conference 4 - 5 December 2014, Hotel Himalaya, Kathmandu, Nepal, ISBN: 978-1-922069-65-8 A large number of “strong” ties, i.e. close friends and relatives, equally contributes to an increase in confidence. While the effect of weak ties is based on the minimisation of risks through the diversification of contacts, the effect of strong ties is based on their strength. In other words, a person can count on the support of a few individuals, but this support will be provided with a greater degree of probability. Thus, the amount of strong ties also affects the level of happiness. Specifically, there are almost twice as many “very happy” people among people with more than 20 close friends than there are among those whose circle of close communication is limited to 1-2 people. In recent years, the social capital of the population has experienced a steady increase. Data analysis has revealed that the weak social ties are growing faster, followed by a slower growth of strong ties. 7. Social capital and the economic behaviour of Russians The structure and amount of accumulated social capital directly affects the economic behaviour of Russians. This is especially visible when it comes to the analysis of employment patterns of the population. As the data at hand indicates, Russians do not tend to put great emphasis on their long-term career development, focussing on instead on the current income amount. In contrast, residents of the developed countries in Europe tend to focus on future prospects and pleasant working conditions. As the data obtained in the 2014 Flash Eurobarometer in Russia indicates, most factors that pertain to the characteristics of the working conditions – such as a convenient work schedule or growth prospects – do not play a decisive role for jobsearching Russians. The single most decisive factor considered when evaluating both current and potential employment is the wage rate. As illustrated by the diagram, the wage rate is considerably more significant (43 percent) than the other factors such as a convenient work schedule (10 percent) the presence of a social package (6 percent) or opportunities for further education (5 percent). 10 Proceedings of International Social Sciences and Business Research Conference 4 - 5 December 2014, Hotel Himalaya, Kathmandu, Nepal, ISBN: 978-1-922069-65-8 Figure 6. For you personally, what was the decisive factor when looking for a new job? salary career opportunities personality of the leader office location schedule social welfare opportunity to be trained team 0.0% 5.0% 10.0% 15.0% 20.0% 25.0% 30.0% 35.0% 40.0% 45.0% For comparison, the Flash Eurobarometer survey conducted in the European Union shows that factors such as a convenient work schedule, a good life-work balance as well as health and safety considerations play a decisive role in assessing current employment (62 percent of EU residents discuss questions regarding health and safety with the employer). The fact that wages turned out to be the single most important factor for employment search in Russia can be explained by the phenomenon that a majority of the population does not see work as being a “long term project” and does not make plans regarding future employment. An absolute majority of Russians (59 percent) claim that they do not make plans regarding their career or future work path. A mere 23 percent plan their employment further than 1-2 years ahead. The virtual absence of long-term career planning can be explained by a general lack of employment security. A 46 percent of Russians believe that they could lose their job within the next two to three years. Just a little over half (57 percent) of people are confident that they could, if necessary, find a job that is not worse than the current one. A long-term employment at the same place still does not provide any guarantees. For those who have held the same job for over ten years, the number of people fearing loss of employment is not different from the national average (46 percent). Indeed, for people who have worked at the same organisation for over 15 years, the number is slightly above average (48 percent). This low confidence in maintaining the current occupation leads to a strong preference for short-term benefits when it comes to finding work. This explains the relative importance of wages over, say, opportunities for further education or comfortable work conditions. 11 Proceedings of International Social Sciences and Business Research Conference 4 - 5 December 2014, Hotel Himalaya, Kathmandu, Nepal, ISBN: 978-1-922069-65-8 Work search strategies additionally depend on the types of channels employed. Russians are reluctant to use employment agencies. According to the 2014 Federal State Statistic Service data, employment services were used by no more than 26 percent of the registered unemployed. For those who managed to find employment, the percentage was even lower. Among those polled during the Flash Eurobarometer, only 4 percent found employment by using a public employment service, and slightly less than 1 percent found work through non-governmental agencies. Figure 7: What kinds of channels did you employ to find work? From relatives and friends appealed to to the employer were invited to the company job search sites in the Internet classifieds for jobs in the media State Employment Service Non-governmental agencies 0.0% 5.0% 10.0% 15.0% 20.0% 25.0% 30.0% 35.0% 40.0% 45.0% 50.0% The most successful and prevalent means of finding work appear to be personal contacts. Forty-seven percent of Russians found their work with help from relatives or friends. Nineteen percent found work by directly contacting the employer. Consequently, a high number of social ties promotes a sense of security: the more acquaintances a person has, the easier it will be for him or her to find work if need be. With increasing numbers of acquaintances, the confidence of finding work rises. The confidence level for uncommunicative people does not exceed 50 percent. In contract, the confidence level approaches 70 percent for the people who have more than 200 acquaintances. This explains why, for Russians, the professional future is determined to a greater degree by their social circle than career prospects at the current place of employment. In addition to the above, long-term employment with the same employer actually leads to a decrease in the number of social ties. The groups of people who have either worked eleven to fifteen, or over fifteen years at the same place of employment also have the highest number of people with 25 contacts or less. The 12 Proceedings of International Social Sciences and Business Research Conference 4 - 5 December 2014, Hotel Himalaya, Kathmandu, Nepal, ISBN: 978-1-922069-65-8 most communicative group are the people who have worked at the same place from three to five years. Thus, if somebody works five years at the same company, their social capital decreases, and, consequently, their chance at finding new work. This trend is amplified if they have worked at the same place for more than ten years. Figure 8. How confident are you about finding new employment if the need arises? 80.0% 70.0% 60.0% 50.0% 40.0% Sure 30.0% Not sure 20.0% 10.0% 0.0% from 1 to 2 years from 3 to 5 from 6 to 10 from 11 to 15 more than 15 As illustrated by the chart, the longer a person works at one place of employment, the less he or she is certain of finding a new job if necessary. The highest confidence levels about future prospects can be found in the group of people who have been working at their current organisation for no more than two years (68 percent are either fully or somewhat certain of being able to find better of similar work). With increasing seniority, this percentage drops. For people who have worked at the same organisation for no less than fifteen years, the percentage decreases to 39%. In contrast, the amount of people who are uncertain of being able to find new work rises twofold – from 32% to 60%. Thus, long-term employment at the same organisation leads to a decrease of social capital and, consequently, lowers the chances of finding new employment that is not inferior to the current one. As a result of this trend, emphasis is not placed on long-term career prospects but rather on short-term employment with high pay. This appears to be a viable strategy in both the shortand long-term: on the one hand, this allows one to obtain the maximum of financial benefits here and now; on the other hand, the strategy allows for a diversification of a person’s social capital and an improvement of their position on the job market. 8. Case study: why do seniors work? Despite a high degree of confidence in receiving support from relatives, about half of all Russian seniors under the age of sixty-five choose to remain part of the 13 Proceedings of International Social Sciences and Business Research Conference 4 - 5 December 2014, Hotel Himalaya, Kathmandu, Nepal, ISBN: 978-1-922069-65-8 workforce. Having said so, their income is only slightly (ten to fifteen percent) above the income of unemployed seniors. In other words, employment does not represent the main guarantor of economic stability (such guarantors tend to be relatives). Work does not significantly raise financial wellbeing. Thus, earnings do not appear to be the main reason for seniors that continue to work. Primarily, it seems, employment allows seniors to retain active social contacts. After fifty to sixty life years, social capital (strong and weak ties), tends to decline sharply. On average, it is 2 to 2.5 times lower than the social capital of people in the forty to fifty age range. It is precisely employment that allows people to create new ties (or preserve old ones), thereby compensating for the age-related shrinking of the social circle. Figure 9. Social ties of seniors. 45.0% 40.0% 35.0% 30.0% 25.0% working pensioners 20.0% retired pensioners 15.0% 10.0% 5.0% 0.0% Less than 10 10 25 26-50 51-100 101-200 More than 200 It should be noted that, in contrast to people of non-pensionable age, seniors do not require social capital for their financial security. The main employment-related factor consequently becomes the maximisation of communication. If the economically active, non-pensionable part of the population strives to reduce risks through social ties, seniors attempt to maximise communication. As has been shown in the previous section of this paper, communication and social capital increase the happiness of people – pensioners are no exception. Thus, among working seniors there are fifteen to twenty percent happier respondents than among unemployed pensioners. 14 Proceedings of International Social Sciences and Business Research Conference 4 - 5 December 2014, Hotel Himalaya, Kathmandu, Nepal, ISBN: 978-1-922069-65-8 Figure 10. Number of strong ties and respondent age. 45.0% 40.0% 35.0% 30.0% From 1 to 2 25.0% From 2 to 5 20.0% From 5 to 10 15.0% From 11 to 20 More than 20 10.0% 5.0% 0.0% Under 25 age 26-35 36-45 46-55 56-65 66-70 71-75 Older than 75 Happiness levels are predominantly influenced by the number of strong social ties. However, the number of strong social ties sharply decreases after the age of 65. Employed seniors compensate their lack of strong ties with weak ties – this allows them to remain integrated into social life. By gaining weak ties through work, seniors remain communicative, while their happiness levels surpass those of the unemployed pensioners. 9. Strategies of borrowing Borrowing patterns are another striking example of the influence of social capital on the financial and economic strategies of Russians. For example, people with a higher number of weak ties are 1.5 – 2 times more likely to borrow money. However, a large amount of any kind of social ties entails financial obligations, such as having to lend money if requested. Overall, a high number of strong ties is associated with more financial obligations than possibilities: people with a high number of social ties tend to lend more often than they borrow. Regardless of whether weak or strong ties prevail, people with a high amount of social capital tend to engage in financial transactions with an above-average frequency. When strong ties prevail, people tend to prefer borrowing money from relatives or close friends. This allows them to feel more comfortable about loan deadlines and the possibility of renegotiating terms. If weak ties are prevalent in the make-up of a person’s social capital, they tend to borrow money from banks. Although such people rarely borrow through informal credit arrangements, they simultaneously have a higher financial confidence. This effect can be attributed to their relative confidence regarding their position within the job market. However, weak ties have almost no effect on long-term financial strategies of the Russian population. For instance, independently of the number of weak ties, 15 Proceedings of International Social Sciences and Business Research Conference 4 - 5 December 2014, Hotel Himalaya, Kathmandu, Nepal, ISBN: 978-1-922069-65-8 disparate population groups will choose approximately the same retirement-time strategies. This being said, strong ties - in their role of determining economic confidence – form the basis for planning long-term financial strategies. The sense of security allows people to depend on the help from relatives and close friends when reaching the age of retirement. Social capital also affects people’s willingness to engage in risky financial deals. People with a significant amount of social capital are more likely to take risks. When it comes to risky transactions, it is crucial to feel some degree of security. This security is achieved through having a large number of weak ties. People with a small number of weak ties tend to be quite reluctant to engage in risky deals. The growing economic optimism, in turn, is linked to changing patterns of national economic behaviours. In comparison to 2013, there has been a rise in risk-taking among the low-income segment of the population. Saving strategies have changed as well: decrease in income coincides with increase in spending. The more optimistic people are regarding the future economic situation, the more relaxed they are about spending - and not saving - money. Pessimistically minded Russians, conversely, prefer to save up money; almost half (49 percent) of people with a pessimistic outlook on the economic future prefer to save money rather than spending it. 10. Conclusion Economic behaviour of agents appears to be patterned by their self-assessed level of subjective wellbeing, which can be defined by the following parameters: satisfaction with the current state of the economy, life satisfaction, political satisfaction, one’s own position in the social hierarchy as well as the level of optimism regarding the coming year. However, as further analysis has revealed, these parameters are not self-sufficient – they themselves are reliant upon a number of factors. A “determinant in the last instance” turned out to be the level, distribution, structure and proportion of different types of capital among segments of the population. While national patterns of economic behaviour are known to be determined by cultural, social and economic capital, it is social capital in particular that explains the main differences between the clusters of economic players – groups of inhabitants of the Russian Federation, differentiated by their different strategies of economic behaviour. 16