Proceedings of 7th Global Business and Social Science Research Conference

advertisement

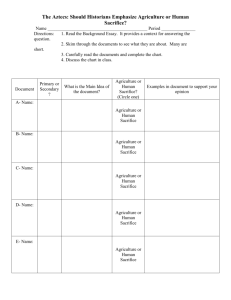

Proceedings of 7th Global Business and Social Science Research Conference 13 - 14 June, 2013, Radisson Blu Hotel, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-26-9 A Customer-Perceived Value Model for e-Service Context Connie Chang* and Yu-Hsu Sean Hsu** The purpose of this study is to investigate online customer-perceived value in relation to the online purchase of tourism products in Taiwan. This study synthesises findings from these areas in order to identify the key antecedents and consequences which influence customer-perceived value in a B2C e-commerce setting. The customer-perceived value model is developed which broadens the value literature by integrating a range of key variables into a single theoretical framework. A mixed-method research approach has been employed in order to gather in-depth data from a wide area, thereby enhancing the reliability and validity of the analysis. The findings suggest that Taiwanese consumers place greater importance on the sacrifice associated with purchasing tourism products than they do on the price, quality and satisfaction elements. The proposed customer-perceived value model explains greater variance in the value construct than other models from the literature, indicating strong analytical support for the framework JEL Codes: 07, 16, 21 1. Introduction Customer perceived value has been examined in the marketing literature for almost two decades (Brady and Robertson, 1999; Chen and Dubinsky, 2003; Holbrook, 1999; Zeithaml, 1988). This reflects the centrality of goods and services in everyday life, and the importance of value decisions within the buying process. Yet the crux of customer-perceived value has not yet been clearly identified, nor have the relative relationships between price, quality, sacrifice and satisfaction been fully explored. As markets have become increasingly competitive, customers have become more demanding, expecting increasingly diverse shopping channels to be provided to satisfy their needs. As a consequence of this changing shopping behaviour, determining customer-perceived value has become even more complex. The e-commerce boom is one example, bringing with it greater opportunities for consumers to shop online for products and services of all kinds. Given that this channel is also associated with greater convenience, competitive prices and time saving, there are inevitably implications for how consumers evaluate perceived value. This paper proposes and tests a model of customer-perceived value using consumer data from the market for online tourism products in Taiwan. The study takes a holistic view of customer-perceived value, synthesising research from the disciplines of axiology, economics, psychology and marketing. The goals are (i) to conceptualise the customer-perceived value model; and (ii) to test this model is a second-order reflective model of customer-perceived value. Even though the existing marketing literature regards factors such as price, quality, value, sacrifice and satisfaction as higher-order constructs (Brady and Cronin, 2001; Monroe, 2003; Roselius, 1971), very few customer-perceived value models have been conceptualised in this manner (see Fassnacht and Koese, 2007; Lin et al., 2005). ____________________________________ Dr. Connie Chang, Graduate School of Business Administration, Meiji University, Tokyo, Japan, connie@kisc.meiji.ac.jp 1 Proceedings of 7th Global Business and Social Science Research Conference 13 - 14 June, 2013, Radisson Blu Hotel, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-26-9 2. Conceptual Framework Most service marketing models capturing customer-perceived value have been developed in the offline setting, although some authors have suggested that these models could potentially be applied to the online context (Gummerus et al., 2004). However, as the number of people shopping on the Internet increases, it is timely to reflect on whether these new shopping channels are altering the notion of customer-perceived value. Bitner and Brown (2000) are among those who argue that there is now a need for further empirical investigation to determine if the conceptual factors established by offline service encounters can also be applied in an online setting. The infusion of technology, increasing product intangibility, security and privacy issues associated with online shopping add to its complexity. These issues could lead to psychological and financial problems for online customers. Not being able to see or touch the actual product might lead to a bad purchase decision, online payment has the potential for credit card fraud and there is a possibility of product delivery failure. Any of these issues could potentially impact upon the measurement of constructs in the offline setting compared with the online context. This paper contributes to this gap in the literature by proposing a conceptual model which examines customer-perceived value in the online setting. The conceptual model builds upon previous studies of customer-perceived value by including new sub-dimensions relevant to the B2C e-commerce setting (Andreassen and Lindestad, 1998; Cronin et al., 2000; Monroe, 2003; Patterson and Spreng, 1997; Oliver, 1999) The model also comprehensively links customer-perceived value with its key antecedent and consequent factors. The different sources presented in Table 1 strongly suggest that quality, price and sacrifice are antecedents of customer-perceived value. In addition, Oliver (1999), and Patterson and Spreng (1997) propose that satisfaction could be a consequence of customer-perceived value, although only Patterson and Spreng’s (1997) theory has been empirically tested. The models of Cronin et al., (2000) and Oliver (1999) suggest that sacrifice has an effect on both value and satisfaction. However, it is important to note that the sacrifice construct in each case refers exclusively to financial sacrifice, even though customers may sacrifice other things in order to acquire the product or service, such as non-monetary cost (i.e. time, effort and inconvenience), performance sacrifice, psychological sacrifice and so on. This has implications for the usefulness of models which assume that financial sacrifice alone affects customer consumption. 2 Proceedings of 7th Global Business and Social Science Research Conference 13 - 14 June, 2013, Radisson Blu Hotel, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-26-9 Table 1 Prior research on the main antecedents and consequences of customer-perceived value. Relationship Reference Q→V Quality is an input to value (Bolton and Drew, 1991; Cronin et al., 2000; Parasuraman and Grewal, 2000). Q → V → Sat Cronin et al., (2000) examine the relationships between quality, value and satisfaction in six industries. V → Sat Satisfaction is the consequence of value (Andreassen and Lindestad, 1998; Cronin et al., 2000; Patterson and Spreng ,1997). Sac → V → Sat Cronin et al., (2000) examine the relationships between sacrifice, value and satisfaction. P→Q→V Price-quality-value relationship (Monroe, 2003). (Note: Q= Quality, V= Value, Sat= Satisfaction, Sac= Sacrifice, P= Price) Monroe (2003) proposes the price-quality-value relationship. In his research, the price construct contains both monetary and non-monetary costs. Other research categorizes non-monetary costs as underlying the sacrifice construct (e.g. Cronin et al., 2000), or treats monetary cost and non-monetary cost as two constructs (Zeithaml, 1988). To address this gap, the price construct in the proposed model also contains two sub-dimensions: monetary cost and non-monetary cost. Other aspects related to sacrifice (i.e. performance sacrifice, psychological sacrifice, technological sacrifice) are measured in the sacrifice construct. Oliver’s (1999) model suggests that satisfaction has a direct effect on customer-perceived value and that value then yields value-based satisfaction. This appears to show that satisfaction has a dual role in consumption and that it can be both antecedent and consequent to customer-perceived value. According to Oliver’s model (1999), the first type of customer satisfaction is developed under several circumstances. It may result from performance outcomes (e.g. product effectiveness), quality (e.g. service quality) or cost-based value (e.g. low price/cheap). On the other hand, a customer may feel dissatisfied with either of the afore-mentioned outcomes, resulting in a negative impact on customer-perceived value. When evaluating a particular offering, the model suggests that a customer makes a purchase decision on the basis of perceived value, not solely on the basis of minimising the price paid or of maximising product benefits. It is important to recognise that there can be considerable divergence in the weighting of different factors which influence a customer’s decision process. Thus, a customer’s perception of each variable relates also to how the others are viewed. For this reason, customer-perceived value is currently one of the most intriguing topics for researchers in service marketing (Rust and Oliver, 1994). In this study, in accordance with Oliver’s theory, satisfaction is viewed as an antecedent to value as well as a consequence, a view supported by research suggesting that satisfaction is derived from customer-perceived value (Patterson and Spreng, 1997). In this study, this second type of satisfaction is termed ‘value-added satisfaction.’ The proposed customer-perceived value model is shown in Figure 1. According to Chin (1998), the hypothesis of the model is formulated as follows, H0: The proposed customer-perceived value model fits to the observed data. 3 Proceedings of 7th Global Business and Social Science Research Conference 13 - 14 June, 2013, Radisson Blu Hotel, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-26-9 Figure 1 The Customer-perceived Value Model Monetary Price 1 Price F Non-monetary Price Product Quality Service Quality 1 Quality F Website Quality System Quality Privacy Security Value F 1 Sacrifice F Service Sacrifice Assurance Value-added Satisfaction Satisfaction F 3. Methodology A mixed-method approach is employed. Firstly, a total of forty interviews were conducted within 20 travel agencies, all of which were based in Taipei. The average work experience in the travel and tourism industry for respondents was 10.87 years. The interviewees were General Managers, Marketing Managers, IT staff and customer service staff. The interviews, which lasted from forty-five minutes to three hours, were conducted in Mandarin and Taiwanese. During the interviews, the managers were asked to discuss their opinions of customer-perceived value, price, quality, sacrifice and satisfaction in relation to purchase experience. In addition, they were encouraged to speak freely about their personal views on the customers and the development of the e-tourism market. Next, forty-five consumers who had purchased tourism products within the last six months to ascertain their experience and views about value were interviewed. These interviews, each of which lasted from forty minutes to one hour, allowed the researcher to explain the purpose of the research and the questions to the consumers. During the interviews, the consumers were asked to describe the process of their most recent online experience and provide some examples of the different stages in buying (i.e. searching for information, comparing products and suppliers and consulting). Thirteen males and thirty-two females participated in the interviews. Most of these individuals were located in Taipei. Their average age was 32.78 years old and their average annual income was 727,667 NTD which equates to 24,978.77 USD (The exchange rate at the time was 29.1314 NTD to 1 USD).The majority had studied at least to undergraduate level. By systematically analysing both sets of data, similarities and differences were highlighted. The insights gained about the consumer decision process and the market contexts were used to develop the questionnaire. 4 Proceedings of 7th Global Business and Social Science Research Conference 13 - 14 June, 2013, Radisson Blu Hotel, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-26-9 3.1 Scale Development A 40-item scale was developed, consisting of 28 items from previous research and 12 items from the literature review and in-depth interviews with consumers and managers (see Table 2). Items that appropriately captured the essence of the constructs were retained in the scale, whereas items that were deemed inappropriate in terms of wording and meaning or whose meaning was unclear were excluded. Experts specialising in the marketing, tourism, linguistics and e-commerce fields were then asked to judge the items. These experts were asked to rate how well each of the items reflected the different dimensions of online customer-perceived value (Churchill, 1999). This process led to the retention of 40 items. Price was measured using six items underlying monetary price and non-monetary prices constructs respectively, which assess the degree of price the respondents felt during the purchase process. All six items were close-ended, with a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. Perceived quality is emphasised in the importance of the human factor, product quality and service quality in the online quality dimension. Fourteen items were developed underlying product quality, service quality, website quality and system quality constructs. Sacrifice portrays the degree of perceived sacrifice via 11 items. Three first-order constructs were developed; they are privacy and security, service sacrifice and assurance. Satisfaction is reflected in how satisfied the customer is during the information and purchase stage. Three items, based on the work of Donthu and Garcia (1999) and Oliver (1997), were used to evaluate the degree of satisfaction during interaction with the website. Perceived value describes how customers assess the degree of perceived value. Three items were adapted from Dodds et al. (1991), Mathwick et al. (2000) and Holbrook (1999). Value-added satisfaction involves the extent to which the customers feel satisfied throughout the entire purchase process. Four items were adapted from Lam et al. (2004), Dabholkar et al. (1996) and Brady and Cronin (2001). Although some discussions related to a minimum number of indicators per construct to be used in SEM, Kenny (1979: 179) states that “two might be fine, three is better, four is best, and anything more is gravy.” Therefore, the scale is deemed to appropriate for further analysis. 5 Proceedings of 7th Global Business and Social Science Research Conference 13 - 14 June, 2013, Radisson Blu Hotel, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-26-9 Table 2 Measurement Item Description Item X1 X2 X3 X4 X5 X6 X7 X8 X9 X10 X11 X12 X13 X14 X15 X16 X17 X18 X19 X20 X21 X22 X23 X24 X25 X26 X27 X28 X29 X30 X31 X32 X33 X34 X35 X36 X37 X38 X39 X40 Description When I first entered the website, I immediately looked for special offers. Price was the most important factor when making a comparison. I judged the price according to market price knowledge. While searching for product information, I felt the website saved me time. While searching for product information, I felt the website aided my research effort. While searching for product information, I felt the website minimised personal inconvenience. The required information was obtained quickly. The site had legible images, colours and texts. The site used simple language. The site provided accurate and relevant information. I received a personalised email which stated who was assisting me and gave me a contact telephone number. The direct line provided in the personalised email was promptly connected for live help. Direct talk to the person who was responsible for my case did not take an inordinate amount of time or effort on my part. These services (personalised email and contact number) enhanced my appreciation of the company. The site was visually appealing. The site displayed a high level of artistic sophistication. The site represented a quality company. There were no errors or crashing. There was no busy server message. There were no pages “under construction.” The general privacy policy was clear and therefore easy to understand. The site clearly explained how user information would be used. Information regarding security of payment was clearly presented. There were trust logos present (e.g. TRUSTe). There were logos of companies stating that my information on this site was secured (i.e. Verisign). In order to minimise uncertainty, I phoned the company first. In order to minimise uncertainty, I visited the company in person. In order to minimise uncertainty, I chose a company with government and Tourist Board accreditation. In order to minimise uncertainty, I consulted my friends. I chose this website because this site has a good reputation. I chose this website because it offered a product I wanted. The personalised email made me feel I was respected. I was very satisfied with these services (personal email and contact number). Value means the quality obtained for the price I paid. I made a purchase decision on the basis of perceived value not solely on the basis of minimising the price I paid or maximising product benefits. I received a certain standard of product quality, a suitable level of customer service and fair price. Overall, I was satisfied with the site. Overall, the service of this site came up my expectations. Overall, during my interaction with the site the quality of customer service was excellent. On comparing what I paid for what I got, this experience appeared to be good value for money. 6 Proceedings of 7th Global Business and Social Science Research Conference 13 - 14 June, 2013, Radisson Blu Hotel, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-26-9 The questionnaire was administered by online travel agents in Taiwan, using a systematic sampling method whereby every second customer on their databases was provided with a link to the online questionnaire. A total of 914 usable questionnaires were obtained within the 4 months allowed for data collection. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used to analyse the data. This approach was deemed appropriate for exploring customer-perceived value (Brady et al., 2005), since it is capable of simultaneously classifying relationships among multiple constructs, thus overcoming the disadvantages of other multivariate techniques (Hair et al., 2009). 4. Empirical Analysis and Results 4.1 Preliminary Analysis The final sample included a total number of 914 usable cases. The sample was slightly dominated by female respondents (462 cases, 50.9%) and the majority of the respondents fell in the 30-39 age group followed by the 25-29 age group. Approximately 75.1% of the respondents were married. Most were professionals; 115 participants worked in the information service industry, 75 worked in information technology, 114 were self-employed, 94 worked in public service and 79 were students. Finally, 55.8% of respondents reported going on holiday once a year, 22.3% went twice, and 10.3% did not go on holiday every year. More than half the respondents (61.5%) preferred to take day trips. Approximately 24.1% of respondents were making an online tourism or travel purchase for the first time, while 75.9% had more than one such shopping experience during the preceding 12 months. Most of the respondents who completed the questionnaire had purchased tourism products online two or three times previously. 4.2 Reliability and Validity The Cronbach alpha value of the 40-item is .937, which is considered to be good (Hair et al., 2009). In this study, reliability was assessed by composite reliability. The coefficients for all factors all exceed 0.7, indicating adequate composite reliability (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Validity was evaluated at two levels: discriminant validity and convergent validity. In Table 3, all standardised regression weights achieve .5 and all average variance extracted (AVE) measures exceed 50%, suggesting adequate convergent validity (Hair et al., 2009). In terms of assessing discriminant validity between constructs, the technique suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981) is applied. In this method, the AVE values for any two constructs are compared and should be greater than the corresponding inter-construct squared correlation estimates (see Table 3). In brief, all AVE estimates in Table 3 are greater than the corresponding inter-construct squared correlation estimates, indicating adequate discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). 4.3 Structural Equation Modelling A two-step (CFA and Path Analysis) structural equation modelling strategy employing AMOS 6.0 was employed in estimating parameters. The analysis showed the chi-square test to be significant (762 d.f= 4457.456), rejecting the null hypothesis that the model resulted in perfect fit. However, given the sensitivity of chi-square to large sample sizes (e.g. N >200) (Jöreskog and Sörbom, 1989), absolute fit, relative fit and parsimonious fit measures were also applied. The GFI, CFI, AGFI yielded values of .920, .928 and .944, 7 Proceedings of 7th Global Business and Social Science Research Conference 13 - 14 June, 2013, Radisson Blu Hotel, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-26-9 respectively, supporting the model (Loehlin, 2004). The RMSEA was .073, indicating a good fit, suggesting that the customer-perceived value model is acceptable. Therefore, the second-order model is supported. Table 3 Standardised Factor Loading, AVE and Construct Reliability Item MP NP PQ SQ WQ SYQ PS SS ASS Sat X1 .633 X2 .707 X3 .782 X4 .726 X5 .729 X6 .688 X7 .700 X8 .762 X9 .714 X10 .655 X11 .746 X12 .738 X13 .747 X14 .705 X15 .631 X16 .780 X17 .705 X18 .779 X19 .726 X20 .701 X21 .655 X22 .644 X23 .743 X24 .808 X25 .728 X26 .677 X27 .795 X28 .780 X29 .671 X30 .745 X31 .756 X32 .667 X33 .748 X34 X35 X36 X37 X38 X39 X40 CR .752 .758 .801 .824 .750 .780 .841 .794 .721 .768 AVE .504 .511 .502 .540 .501 .542 .516 .564 .531 .525 8 Value VS .751 .704 .677 .754 .506 .785 .806 .730 .636 .830 .551 Proceedings of 7th Global Business and Social Science Research Conference 13 - 14 June, 2013, Radisson Blu Hotel, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-26-9 (Note: MP represents Monetary Price, NP=Non-Monetary Price, PQ=Product Quality, SQ=Service Quality, WQ=Website Quality, SYQ=System Quality, PS=Privacy and Security, SS=Service Sacrifice, ASS=Assurance, Sat=Satisfaction and VS=Value-added Satisfaction) 5. Discussion of Findings and Implications The results suggest that the proposed customer-perceived value model is acceptable, yielding some interesting insights into the relationships between value and the other constructs. Thus customer-perceived value is shown to be relatively strongly explained by perceptions of sacrifice, with Taiwanese customers shopping for tourism products apparently placing greater weight on sacrifice than they do on the monetary costs and benefits associated with purchase. This is likely to be because the complicated nature of tourism products (i.e. multiple suppliers, service intangibility and inseparability), mean that customers encounter more uncertainties than when purchasing some other service products. The impact of making a wrong decision when buying a holiday or travel product is also considerable, not least because buying a replacement and travelling away again is often not an option. Consequently, consumers may offset this risk by spending more time and effort during the pre-purchase stage in order to ensure that they make the right decision. This was manifest in the customer interviews in this study, as the following quotation illustrates: “Booking a holiday online sounds convenient and quick. Do you know how much time I spend on it? I always spend an awful lot of time in order to make the right decision. I can’t just simply choose a holiday and click on it. You know, if things go wrong because of a wrong decision made, it is we who have to suffer. The whole journey will be a nightmare. We lose not only money, but also our holiday.” While other value research has tended to emphasise the role of prices and quality, the more holistic approach adopted in this study provides evidence of sacrifice as a key decision-making factor for online service customers. The model has also identified key antecedents likely to have an impact upon perceptions of value in the online setting. By combining previous value models from different paradigms and integrating price, quality, sacrifice and satisfaction into one theoretical framework, this model takes a fresh look at the customer-perceived value construct. The model has also been specifically designed for investigating intangible service products in a B2C context. Moreover, value has been shown in this study to be the result of a cognitive comparison process, with cognitive evaluation occurring before the emotional response from which value-added satisfaction stems. In contrast to the cognitive-based value construct, value-added satisfaction is conceptualised as an affective evaluation response (Oliver, 1996). This study also confirms Woodruff’s (1997) conceptualisation which suggests a positive relationship between value and satisfaction. Indeed, the results also support the applicability of the conceptualisation to the e-tourism industry. The results contribute to the modelling of customer-perceived value in several important ways. First, the model broadens the customer-perceived value literature by combining findings from previous research and by integrating a number of key variables into one theoretical framework. Evidence from this study supports the idea that price, quality, 9 Proceedings of 7th Global Business and Social Science Research Conference 13 - 14 June, 2013, Radisson Blu Hotel, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-26-9 sacrifice and value are multidimensional hierarchical constructs. The hierarchical nature of the proposed conceptualisation of value offers interesting insights into customer perceptions of value. These factors (price, quality, sacrifice and value) and dimensions (e.g. non-monetary price, website quality, privacy and security), which have been considered important in previous research, have been specifically developed for the B2C e-commerce setting. This has allowed the measurement of customer-perceived value to take into consideration factors which are not relevant to the traditional offline context. The findings also suggest that researchers studying customer-perceived value need to measure a wider range of factors than previously thought, since the effects of price, quality, sacrifice and satisfaction are both more comprehensive and complex than previously reported. When the effects of price, quality, sacrifice and satisfaction are considered simultaneously, they are shown to directly influence customer-perceived value. This indicates that the model not only highlights the practical significance of each construct but also emphasises the need to adopt a more holistic view of the problem. Finally, the model contributes to previous value models (Brady and Robertson, 2005; Cronin et al., 2000; Patterson and Spreng, 1997; Zeithaml, 1988) in the way it integrates a number of factors into the framework. Brady and Robertson (2005), Cronin et al., (2000) and Zeithaml (1988) overlook the importance of certain aspects of sacrifice, such as psychological factors, in their models. Brady and Robertson (2005), and Cronin et al., (2000) conflate price within the sacrifice construct. Since different types of product (e.g. tangible and intangible) are likely to influence perceptions of value (Woodruff, 1997), a sacrifice construct that excludes financial aspects could better explain customer-perceived value. This suggests that the sacrifice construct plays an important role in making value judgements, irrespective of whether a tangible or intangible product is being purchased. 6. Managerial implications The results have important implications for online travel agents and other online organisations. Clearly, customer-perceived value is an important aspect of the Services Marketing literature. Customer-perceived value is driven by variables such as price, quality, sacrifice and satisfaction that are continually weighted against each other during every day purchases. The findings suggest that appropriate conceptualisation and measurement are important for the effective management of customer-perceived value, particularly in the B2C web-based e-commerce marketplace. Delivering high customer-perceived value is essential for providing positive customer satisfaction. Online purchasing has become more prevalent recently due to lower relative prices and convenience for customers. However, these two factors are not sufficient on their own to win customers over, as website presence, products and low prices can easily be imitated. For example, the layout and function of a tourism webpage is easy for competitors to copy. The webpage analysis suggests that to some extent these tourism web pages were similar to each other, with the company logo located on the top of the webpage followed by search options (i.e. flight ticket, hotel room or holiday package). Company information and accreditations by third parties tend to be placed at the end of the page. This kind of layout can also been seen in UK or US tourism websites (see e-bookers.com or lastminute.com). Not only do organisations copy each other but they also copy successful foreign websites. In terms of price and product, these organisations often tend to sell the same product at the same price. This means that online organisations need to pay greater attention to issues 10 Proceedings of 7th Global Business and Social Science Research Conference 13 - 14 June, 2013, Radisson Blu Hotel, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-26-9 related to sacrifice and customer satisfaction, especially because the results demonstrate that customers place greater emphasis on sacrifice when making decisions to purchase tourism products online. Customers who choose to purchase products or services online are willing to sacrifice something in exchange for good value. A customer’s aim is to minimise the sacrifice components as much as possible and there are certain things that customers can do to avoid significant losses before making payment. They can check the legitimacy of the company by checking its government registration status. Alternatively, they can telephone the company or visit in person, something made evident in both the company and consumer interviews. Some customers are prepared to go to considerable lengths to ensure legitimacy, particularly with regard to money related issues. This implies that online organisations need to reassure potential customers by providing additional information such as the company address, telephone number and government registration number on their websites to assure customers. A further factor revealed by the research findings is that male customers place greater emphasis on the assurance factor. The greater the number of accreditations awarded from third parties, the safer these customers perceive the website to be. This influences whether customers stay or leave the website, as the switching cost online is relatively low to customers. The proposed customer-perceived value model can provide direction to practitioners aiming to improve customer-perceived value, by highlighting the need to consider different aspects of sacrifice and satisfaction. The second-order model demonstrates that there are several levels of abstraction that have to be taken into account. The model presents the multiple dimensions of each of the constructs that are usually considered by customers. As customers become increasingly demanding, they are less tolerant of other areas of poor performance, such as poor service quality or website presence. This suggests it would be beneficial for organisations to evaluate themselves with respect to these constructs and sub-dimensions. 7. Future Research Future research is needed that examines this framework across other industries and respondents. There is potential for interesting comparative studies of a customer-perceived value, using real consumers as respondents. These would provide further opportunities to understand the value concept in different settings as among offline customers who purchase products or services via mail-order or television shopping channels. Since customers are not able to examine the quality of the desired product or service, the sacrifice they face appears to be considerable. The shopping environment in cyberspace, category (e.g. mail order) and on TV channels is rather similar to a bricks-and-mortar shop. Thus, if such a study were to be undertaken, it is possible that the reliability, validity and generalisability of this study would be enhanced. A tourism product was chosen for this study of customer-perceived value because of its intangibility and high monetary, non-monetary and psychological risk. Different product types have varying effects on customer-perceived value, specifically with respect to the relationships between value and price, quality and sacrifice. Physical products, such as juice (Zeithaml, 1988), electronic appliances (Sweeney et al., 1999) and cigarettes (Sheth et al., 1991) and tangible products such as consulting services (Patterson and Spreng, 11 Proceedings of 7th Global Business and Social Science Research Conference 13 - 14 June, 2013, Radisson Blu Hotel, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-26-9 1997), fast food (Brady and Robertson, 2005) and banking services (Roig et al., 2006) are just some of the products that have been considered in previous studies of customer-perceived value. The buying decision process for these products and services involves different degrees of sacrifice and quality, thus affecting the value perceptions of customers and influencing how decisions are made. Further research could explore the impact of different sorts of purchases on the developed model. It would also be particularly interesting to test the measurement on other high risk and intangible services items, such as long-term investment products, where the potentials for higher profits and the higher risk rates is evident. This study is based on details gained at a single point in time. Since customer value varies across individuals, time and circumstances, there might be scope for conducting a longitudinal study of customer-perceived value over time. Such an approach could probe changes in customer perceptions concerning the value of the specific product being assessed. A more experienced customer may have different perceptions of value than a less experienced customer. For example, customers who have less online shopping experience may find this shopping mode frustrating and difficult to manage. This may be particularly so when purchasing more expensive or high risk products online. Unlike traditional bricks-and-motor shops, the self-service feature of e-commerce decreases human service levels and assumes that customers have enough knowledge to help themselves (Moon and Frei, 2000). A more experienced customer may regard this process as less risky and more convenient as a shopping experience than one who is less experienced. This might impact upon the variable which shape customer-perceived value. Moreover, demographic variables such as age, gender, education, occupation, and ethnicity are common factors used for market segmentation (Dibb et al., 2006). There is very little research reporting on gender differences in respect to perceptions of value. Brady and Robertson (1999) were the first to explore customer-perceived value by examining gender differences. Their work in the service industry was located in the USA and Ecuador. According to Hofstede (1980), women and men socialise differently and their perceptions of high versus low value are likely to be affected by their gender. Moreover, Dittmar and Drury (2000) suggest that women are often more psychologically oriented to shopping than men, especially when buying goods other than everyday household products or groceries. It is argued that emotional, social and identity needs play a more important role in women’s shopping behaviour than in men’s. This may influence the attitude of different genders towards online shopping and impact upon their perceptions of value. Future research is needed to estimate the model for different customer segments. Performing a multi-group analysis would be helpful to see how different segments (e.g. men and women, more experienced and less experienced customers, older and younger) perceive value. The research design for such studies would need to take into account the difficulties in obtaining a sufficient sample size of the different segments to perform SEM multi-group analysis. A range of possible extensions to this research have been suggested. Customer-perceived value will continue to play an important role in everyday life as customers weigh up the benefits and costs of one product or service offering relative to another. The dynamic character of value is also readily apparent, with the construct varying across individuals, time and circumstances and being influenced by diverse factors such as personal values, education and income. In view of the dynamic and central nature of customer-perceived value in all our lives, there remains a rich potential for future research. 12 Proceedings of 7th Global Business and Social Science Research Conference 13 - 14 June, 2013, Radisson Blu Hotel, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-26-9 References Andreassen, T. and Lindestad, B. 1998. “Customer loyalty and complex services: the impact of corporation image on quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty for customers with varying degrees of service expertise, International Journal of Service Industry Management”, vol. 9, no.1, pp. 7-23. Bagozzi, R. P. 1992. “The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions and behaviour, Social Psychology Quarterly”, vol. 55, no.2, pp. 178-204. Bitner, M. J. and Brown, S. W. 2000. “Technology infusion in service encounters, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science”, vol. 28, no.1, pp. 138-149. Bolton, R. N. and Drew, J. H. 1991. “A multistage model of customers’ assessments of service quality and value, Journal of Consumer Research”, vol.17, no.4, pp. 375-384. Brady, M. K. and Cronin, J. J. Jr. 2001. “Some new thoughts on conceptualising perceived service quality: a hierarchical approach, Journal of Marketing”, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 34-50. Brady, M. K., Knight, G. A., Cronin, J. J. Jr., Tomas, G., Hult, M and Keillor, B. D. 2005. “Removing the contextual lens: a multinational, multi-setting comparison of service evaluation models, Journal of Retailing”, vol. 81, no.3, pp. 215-230. Brady, M. K. and Robertson, C. J. 1999. “An exploratory study of service value in the USA and Ecuador, International Journal of Service Industry Management”, vol.10, no.5, pp. 469-486. Chen, Z. and Dubinsky, A. J. 2003. “A conceptual model of perceived customer value in e-commerce: A preliminary investigation. Psychology & Marketing”, 20, 323-346. Chin, W. W. 1998. “Issues and opinion on structural equation modelling, MIS Quarterly”, vol. 22, no.1, pp. 7-16. Churchill, G. A. 1999, Marketing Research: Methodological Foundations, 7th Ed, Harcourt Brace College Publishers, New York. Cronin, J. J. Jr., Brady, M. K. and Hult, G. T. M. 2000. “Assessing the effects of quality, value and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioural intentions in service environment, Journal of Retailing”, vol. 76, no. 2, pp. 193-218. Dabholkar, P. A., Thorpe, D. I. and Rentz, J. O. 1996. “A measure of service quality for retail stories: Scale development and validation, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science”, vol. 24, no.1 , pp. 3-16 Dibb, S., Simkin, L., Pride, W. M. and Ferrell, O. C. 2006, Marketing Concepts and Strategies, 5th Ed, Houghton Mifflin, Boston. Dittmar, H. and Drury, J. 2000. “Self-image – is it in the bag? A qualitative comparison between ordinary and excessive consumers, Journal of Economic Psychology”, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 109-142. Dodds, W. B., Monroe, K. B. and Grewal, D. 1991. “Effects of price, brand and store information on buyers’ product evaluations, Journal of Marketing Research”, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 307-319. Donthu, N. and Garcia, A. 1999. “The internet shopper, Journal of Advertising Research”, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 52-58. Fassnacht, M. and Koese, I. 2006. “Quality of electronic services: conceptualising and testing a hierarchical model, Journal of Service Research”, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 19-37. Fornell, C. and Larcker, D. F. 1981. “Evaluating structural equation modelling with unobservable variables and measurement error, Journal of Marketing Research”, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 39-50. Gummerus, J., Liljander, V., Pura, M. and Van Riel, A. 2004. “Customer loyalty to content-based web sites: The case of an online health-care service, Journal of Services 13 Proceedings of 7th Global Business and Social Science Research Conference 13 - 14 June, 2013, Radisson Blu Hotel, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-26-9 Marketing”, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 175-86. Hair, J. F. Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E. and Tatham, R. L. 2009, Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th Ed, Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River. Holbrook, M. B. 1999, “Introduction to consumer value”. in Holbrook. M. B. (Ed.), Consumer Value, A Framework for Analysis and Research, Routledge, New York. Jöreskog, K. and Sörbom, D. 1989, LISREL 7: A Guide to the Programme and Applications, 2nd Ed, Scientific Software, Chicago. Kenny, D. A. 1979, Correlation and Causation, John Wiley, New York. Lam, S. Y., Shanker, V., Erramilli, K. M. and Murthy, B. 2004. “Customer value, satisfaction, loyalty and switching costs: an illustration from a business-to-business service context, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science”, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 293-311. Lin, C.-H, Sher, P. J. and Shin, H.-Y. 2005, “Past progress and future directions in conceptualising customer perceived value, International Journal of Service Industry Management”, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 318-336. Loehlin, J. C. 2004, Latent Variable Models: An Introduction to Factor, Path and Structural Equation Analysis, 4th Ed, Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ. Mathwick, C., Malhotra, N. K. and Rigdon, E. 2001. “Experiential value: Conceptualisation, measurement and application in the catalogue and internet shopping environment, Journal of Retailing”, vol. 77, no. 1, pp. 39-56. Moon, Y. and Frei, F. X. 2000. “Exploding the self-service myth, Harvard Business Review”, vol. 78, no. 3, pp 26-27. Monroe, K. B. 2003, Pricing: Making Profitable Decisions, 3rd Ed, McGraw-Hill, New York. Oliver, R. L. 1996, “Varieties for value in the consumption satisfaction response”, in Corfman, K. P. and Lynch, J. G. Jr. (Ed.), Advances in Consumer Research, 23, Association for Consumer Research, Provo, UT, pp. 143-147. Oliver, R. L. 1997, Satisfaction: A Behavioural Perspective on the Consumer, McGraw-Hill, Boston. Oliver, R. L. 1999, “Value as excellence in the consumption experience”, in. Holbrook, M. B. (Ed.), Consumer Behaviour: A Framework for Analysis and Research, Routledge, New York, pp. 43-62. Parasuraman, A. and Grewal, D. 2000. “The impact of technology on the quality-value-loyalty chain: A research agenda, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science”, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 168-174. Patterson, P. G. and Spreng, R. A. 1997. “Modelling the relationship between perceived value, satisfaction and repurchase intentions in a business-to-business services context: An empirical examination, International Journal of Service Industry Management”, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 414-434. Sheth, J. N., Newman, B. I. and Gross, B. L. 1991, Consumption Values and Market Choices: Theory and Applications, Southwestern Publishing, Cincinnati. Roig, J. C., Fandos, G. J., Sanchez, T., Migue, A. M. and Monzonis, J. L. 2006. “Customer perceived value in banking services, International Journal of Bank Marketing”, vol. 24, no. 5, pp. 266-283. Roselius, T. 1971. “Consumer rankings of risk reduction methods, Journal of Marketing”, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 56-61. Rust, R. T. and Oliver, R. L. 1994, “Service quality: insights and managerial implications from the frontier”, in Rust, R. T. and Oliver, R. L. (Ed.), Service Quality New Directions in Theory and Practice, Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp. 1-20. Sweeney, J. C. and Soutar, G. N. 2001. “Consumer perceived value: the development of a multiple item scale, Journal of Retailing”, vol. 77, no. 2, pp. 203-220. 14 Proceedings of 7th Global Business and Social Science Research Conference 13 - 14 June, 2013, Radisson Blu Hotel, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-26-9 Woodruff, R. B. 1997. “Customer value: the next source for competitive advantage, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science”, vol. 25, no. 2, pp 139-153. Zeithaml, V. A. 1988. “Consumer perceptions of price, quality and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence, Journal of Marketing”, vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 2-22. 15