The Corporate Accountability Movement: Lessons and Opportunities

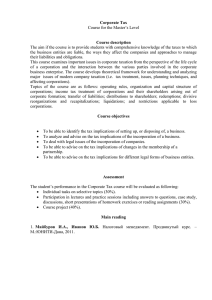

advertisement