Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference

advertisement

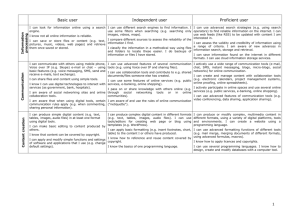

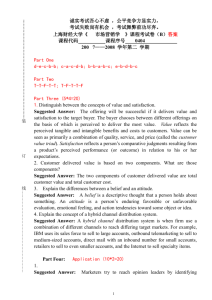

Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 Effect of Trust on Customer Intention to use Electronic Banking in Vietnam Long Nguyen1, Duc Tho Nguyen2 and Tarlok Singh3 Vietnam is a developing country with a population of approximately over 90 million (11/2013). The availability of electronic banking (e-banking) over ten years ago in Vietnam marked a significant development for society in general and for banking in particular. Research attention has so far focused on the development and implementation of e-banking applications in Vietnam. However, there is at present very little research about customer trust in Vietnamese e-banking. Most of research about e-banking in Vietnam focuses on the adoption of e-banking. This paper, part of an investigation of critical factors affecting customer trust in ebanking, explores the effect of trust on aspects of customer intention to use ebanking in Vietnam. The proposed research model integrates constructs from other disciplines, such as psychology, sociology, and electronic commerce. The basic model for this study has been adopted from the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to show the characteristic of e-banking, including the addition of another belief, trust, to increase the understanding of customer intention to use ebanking in Vietnam. A Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approach has been used to evaluate the research model. This study begins to fill in the gap noted in the literature by providing a model for the effect of trust on customer intention to use e-banking. The study’s findings offer help for Vietnamese banks, policy makers and customers to clarify and develop the effect of trust on customer intention in using these e-banking services. Keywords: customers’ intention, e-banking, trust, TAM 1. Introduction Many banks around the world have launched their e-banking to provide customers with more convenient ways to access banking information and services. Previous research has been carried out to evaluate the quality and quantity of the e-banking services provided, as well as the overall adoption of e-banking. The results and findings of this research differed, based on many factors such as the level of development of the particular country, its national culture, the customers’ knowledge of e-banking and the infrastructure of information technology. In Vietnam, e-banking research focuses on the adoption model, the drivers of customer intention to use e-banking, and the use of e-payment. None of this research studied customer trust in e-banking, even though trust plays an important role in e-commerce adoption, especially e-banking transactions, and trust is one of the most significant factors in customer acceptance of e-banking (Suh and Han, 2002). Most of the existing literature about trust in e-banking assumes trust to be a factor affecting customer acceptance of e-banking (e.g. Suh and Han, 2002; Alsajjan and Dennis, 2006; Kassim and Abdulla, 2006; Benamati and Serva, 2007; Grabner-Kräuter and Faullant, 2008; AldásManzano et al. 2009; AbdullahAl-Somali et al. 2009; Muñoz-Leiva et al. 2010; Dixit and Datta, 2010; Khalil Md Nor et al. 2010; and Anita Lifen Zhao et al. 2010). In addition, other studies investigated factors affecting the adoption and usage of e-banking in general and 1 Long Nguyen, Department of Accounting, Finance and Economics, Griffith University, Australia. Email: l.nguyen@griffith.edu.au 2 Duc Tho Nguyen, Department of Accounting, Finance and Economics, Griffith University, Australia. Email: t.nguyen@griffith.edu.au 3 Tarlok Singh, Department of Accounting, Finance and Economics, Griffith University, Australia. Email: tarlok.singh@griffith.edu.au 1 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 internet banking in particular (e.g. Sathye, 1999; Tan and Teo, 2000; Wan et al. 2005; Chiemeke et al. 2006; Ndubisi and Sinti, 2006; Wang and Pho, 2009; and Alain Yee-Loong Chong et al. 2010). These studies concluded that many factors affect the acceptance and usage of e-banking, including education, technology acceptance, security, risk, legal support, trust, demographic characteristics. The main aim of this study is to identify the effect of trust on customer intention to use ebanking in Vietnam. The basic model for this study has been adopted from the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989) to show the characteristic of e-banking. The TAM model is an integrated construct from disciplines such as psychology, sociology, and electronic commerce. Another belief, trust, is added to the TAM to increase the understanding of customer intention to use e-banking in Vietnam. A Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approach is used to evaluate the research model. This study differs from the previous studies in that it conducts a comprehensive primary survey to collect data to be used in the model. The survey encompasses selected provinces in northern, central, and southern of Vietnam. This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides the research background and discusses the Technology Acceptance Model and trust in ebanking. Section 3 outlines the study’s model and sets the hypotheses. The research methodology and data used in the study are discussed in Section 4. Section 5 presents empirical results and Section 6 gives the conclusions. 2. Research background As noted, this study adds another belief, trust, to the TAM to find out the effect of trust on customer intention to use e-banking in Vietnam. This section outlines how TAM applies to e-banking as the basic model in explaining the customers’ acceptance of technology. Then the definition, the literature of trust in using e-banking and the role of customers’ trust are discussed. 2.1 Technology Acceptance Model The TAM is a model developed by Davis (1989) and Davis et al. (1989) to explain why users accept or reject information technology (Figure 1). It is based on Ajzen and Fishbein’s Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) model, a general model that suggests an individual’s social behaviour is motivated by his/her attitude towards the behaviour. This theory is based on assumptions that human beings are usually quite rational and make systematic use of the information available to them (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). TRA is concerned with the determinants of intended behaviours, saying that a person’s intentions are a function of two basic determinants, one which is personal in nature (attitudes) and the other which reflecting social influence (social or subjective norms). The major application of this theory is in the prediction of behavioural intention, including predictions of attitude and predictions of behaviour. The subsequent separation of behaviour intention from actual behaviour allows some explanation of the limiting factors on attitudinal influence (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). The TAM suggests that perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU) are the primary relevance for technology acceptance behaviour. PU is defined as the degree to which a prospective user believes that using a particular system would enhance his or her job performance. PEOU is defined as the degree to which a prospective user believes that using a particular system would be free of effort (Davis, 1989). Adopted from the TRA model, the TAM shows that these two beliefs (PU and PEOU) specify first the attitude 2 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 towards using information systems, then the attitude towards using determining the behavioural intention to use; lastly, the behavioural intention to use leads to actual use (Suh and Han, 2002). The TAM does not include social norms (SN) as a determinant of behavioural intention. This model has been widely applied for predicting the acceptance of information technology; its validity has been demonstrated across a wide variety of information technology systems (Plouffe et al., 2001). Figure 1: Technology Acceptance Model External variables Perceived Usefulness (PU) Perceived Ease of use (PEOU) Attitude towards Using (ATU) Behavioural Intention to use (BI) Actual Use The TAM explains the causal linkages between these two beliefs (perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use of the information system) and users’ attitudes, intentions and actual computer adoption behaviour (Davis et al., 1989). It suggests that perceived ease of use (PEOU) and perceived usefulness (PU) are the two most important factors in explaining user acceptance of using the information system. 2.2 Trust in e-banking Trust is a very complex construct and it is multidimensional (Gefen 2000; Hoy & Tarter, 2004; Smith & Birney, 2005; Mcknight et al., 2002; Mayer et al., 1995). Various definitions of trust depend on the different research areas. It is “believing in the honesty and reliability of others” (World Reference, 2005). Trust is also the willingness to rely (Doney and Cannon, 1997) and is a positive form of behaviour to others (Whitener et al., 1998). According to Yousafzai et al. (2003), trust is “the belief that a party’s word or promise is reliable and a party will fulfil his/her obligations in an exchange relationship”. Trust occurs “when one party has confidence in an exchange partner’s reliability and integrity” (Morgan and Hunt, 1994). Trust is “the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party, based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party” (Mayer et al., 1995). These definitions of trust are applicable to the relationship between (at least) two parties – a trustor and a trustee; the object of trust is another person or a group of persons (Grabner-Kr.autera and Kaluscha, 2003). Trust in an online vendor is the “willingness to make oneself vulnerable to actions taken by the trusted party based on the feeling of confidence and assurance” (Gefen, 2000). Trust is “the belief that the promise of another can be relied upon and that, in unforeseen circumstances, the other will act in a spirit of good will and in a benign fashion towards the trustor” (Suh and Han, 2002). Trust is “the subjective assessment of one party that another party will perform a particular transaction according to his or her confidant expectation, in an environment characterized by uncertainty” (Ba and Pavlou, 2002). The most popular definition of trust is the following: “Trust is a psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intention or behaviour of another under conditions of risk and interdependence” (Rousseau et al., 1998). Customers’ trust in their online transactions is very important and has been identified as a key to the development of e-commerce (Yousafzai et al., 2003). A key reason for focusing 3 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 on the importance of trust in e-commerce in general and in e-banking in particular is the fact that in a virtual environment the level of risk in an economic transaction is higher than it is in traditional settings (Grabner-Kr.autera and Kaluscha, 2003). The uncertainty that challenges online customers is because suppliers on the Internet are inevitably independent and unpredictable, whereas in transactions there is a need for customers to understand the suppliers’ actions. If customer uncertainty is not reduced, transactions between online customers and suppliers will not be performed. Trust is one of the most effective uncertainty reduction methods (Gefen, 2000). In the Internet environment, users from everywhere are able to access files online and information is transferred via Internet. Therefore e-banking is risky from the viewpoint of security. E-banking seems highly uncertain because users involved in a transaction are not in the same place (Ratnasingham, 1998). Customers cannot tell or observe a teller’s behaviour directly, thereby increasing the uncertainty. Due to this, customer trust is a major factor influencing the development of e-banking. Researchers have empirically indicated that customer trust plays a very important role in e-banking website loyalty, which can be defined as a customer’s strong desire to keep a valued relationship with a bank (Macintosh and Lockshin, 1997). Numerous research studies have identified lack of trust as one of the main reasons why customers are still reluctant to conduct their financial transactions online (e.g. Wong et al., 2009). In order to use e-banking in real life as a viable medium financial service delivery, banks must try to fill the trust gap created due to the higher degree of uncertainty and risk in an online banking environment compared to the environment of traditional transactions. Many studies conducted examining the role of trust in e-banking (e.g. Suh and Han, 2002; Casaló et al., 2007; Lichtenstein and Williamson, 2006) found that trust plays a very important role in the adoption and continued use of e-banking. Moreover, not only does affect the intention of using e-banking (Suh and Han, 2002; Liu and Wu, 2007), but trust in e-banking has also been found to be an antecedent in the e-banking environment (Kassim and Abdulla, 2006; Vatanasombut et al., 2008), so that trust can reduce perceived risk in an online environment. Online banking transactions require collection of very sensitive information about customers (Gefen, 2000; Morgan and Hunt, 1994). Customers always fear to disclose their privacy and financial information on the internet, because of security problem and distrust of e-banking providers (Suh and Han, 2000). The role of trust is very important when e-banking providers publicize their services (Palmer and Bejou, 1994). Thus, trust has a significant effect on the customer intention of using e-banking (Alsajjan and Dennis, 2006). The requirement of trust is more important in the virtual environment than in the real environment (Ratnasingham, 1998). 3. Model and the Hypotheses setting 3.1 The model The research model for this study investigates the effect of trust on customer intention of using e-banking by adding this additional belief, trust, to the original TAM. This research model is adopted from Davis (1989) and Suh and Han (2002). E-banking has many advantages, when compared with traditional banking methods. It provides enormous benefits to banks, to customers and to economies. E-banking also has disadvantages that bring many challenges for banks, such as security and privacy, cost and risk. These disadvantages raise the important question: how to develop a safe 4 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 environment for e-banking transactions-especially regarding customer trust in using ebanking. Solving this problem is even more critical for e-banking, as any payment or deposit necessarily uses a virtual savings account (Muñoz-Leiva et al., 2010). Figure 2: Model and the hypotheses H7 Perceived Usefulness (PU) External variable s H3 H5 H9 Perceived Ease of use (PEOU) H6 Attitude towards Using (ATU) H8 Behavioural Intention to use (BI) H2 H4 Trust (TEB) H1 3.2 Hypotheses setting Researchers in marketing areas have empirically tested the causal relationship between trust and behavioural intention. Alain Yee-Loong Chong et al. (2010) found that trust will affect the intention to adopt internet banking, as without private security and privacy protection, customers will not use online banking services. Suh and Han (2002) concluded that trust is one of the most significant beliefs in explaining customers’ behavioural intention to use internet banking. Doney and Cannon (1997) found that customer trust related to their intention to use the vendor in the future. Gefen (2000) showed that trust issues play an important role in increasing customers’ intention to use the e-vendor’s website. This leads to hypothesis 1 as follows: Hypothesis 1 (H1): Trust has a positive effect on the behavioural intention to use ebanking. In the marketing areas, many studies have found that trust has an effect on attitude. Macintosh and Lockshin (1997) concluded that customers’ store trust is positively related to store attitude. Store attitude was considered as one of the components of store loyalty. Suh and Han (2003) suggested that trust has a positive impact on customer attitude towards using e-commerce for trade transactions. Wang (2010) also showed that customers’ perceived trust towards mobile phone advertisement enhanced their attitudes towards advertisement in a mobile phone company. Limbu et al. (2012) suggested that customer trust in online retailer websites positively influence the customers’ attitudes towards the online retailers’ websites. This leads to hypothesis 2 as follows: Hypothesis 2 (H2): Trust has a positive impact on the attitude towards using e-banking. According to Davis (1989), the TAM suggested that perceived usefulness is one of two beliefs (perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use) that are most relevant to 5 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 information systems acceptance behaviours. In this study, another belief, trust, was added into the TAM to verify its effect on customer intention to use e-banking. Prior studies using the TAM variables such as Suh and Han (2002), Koufaris and Hampton-Sosa (2004) have shown that perceived usefulness had a significant impact on trust, so we expect that perceived usefulness will have strong positive effect on trust in e-banking. This leads to hypothesis 3 as follows: Hypothesis 3 (H3): Perceived usefulness has a positive impact on trust in e-banking. We also test the following TAM related hypotheses in the e-banking environment because this research model is based on the TAM. Hypothesis 4 (H4): Perceived usefulness has a positive impact on the attitude towards using e-banking. Hypothesis 5 (H5): Perceived usefulness has a positive impact on the behavioural intention to use e-banking. Hypothesis 6 (H6): Perceived ease of use has a positive impact on trust in e-banking. Hypothesis 7 (H7): Perceived ease of use has a positive impact on the attitude towards using e-banking. Hypothesis 8 (H8): Perceived ease of use has a positive impact on perceived usefulness. Hypothesis 9 (H9): Attitude towards using e-banking has a positive impact on the behavioural intention to use this form of banking. 4. Research methodology and the Data 4.1. Research methodology The research model is estimated using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), a family technique that is used to analyze and empirically explain the relationships among constructs (Hair, 2009; Kline, 2010). According to Hair (2009), the focus of SEM as an analysis technique is the covariance and correlation parameters between the constructs, a distinguishing characteristic of SEM analysis techniques (Byrne, 2013). This approach is chosen because of its ability to test causal relationships between constructs with multiple measurement items (Jöreskog and Sörbom, 1993), and because it has the capability of testing the measurement characteristics of constructs (Hair, 2009). The SEM approach offers several advantages over the conventional regression approach in this context, basically providing greater facility in handling multicollinearity, inherent errors in measuring independent variables, and estimation of parameters across a system of simultaneous equations (Titman and Wessels, 1988; Hoyle, 1995; Hair, 2009; Chang et al., 2009). The models are then evaluated by the maximum likelihood method using AMOS software distributed by SPSS software version 20. 4.2. Field Survey Design and the Data collection This study uses primary data collected from the questionnaire survey in selected provinces in northern, central, and in southern of Vietnam to test the hypotheses. The questionnaire was presented to participants in two ways: either as hard-copy questions directly in bank customer meetings or as a link to the Web survey site (https://prodsurvey.rcs.griffith.edu.au/prodls190/index.php?sid=63492&lang=en) sent by email to bank customers. In total, there were 557 responses; 93 out of these samples were not used because there were missing values. The rest, 464 samples, were gathered and eligible for data analysis (178 samples supported via the Web survey; 286 samples collected via bank customer 6 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 meetings). Direct delivery of the survey questionnaire and sending via email addresses to participants were preferred rather than using postal surveys because the postal service in Vietnam is not reliable and the use of online surveys would exclude non-adopters of ebanking services. There are no missing data in the sample because online participants could not submit their online responses with missing values via the Web survey and all hard copies of the questionnaire survey with missing values were deleted before importing data into the computer. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the respondents. Table 1: Descriptive statistics of respondent’s characteristic Respondents characteristics Gender Age Education Occupation Income (in million VND) Frequency use the Internet First visit ebanking website Value Male Female Under 20 21-30 31-40 41-50 51-60 Above 60 High school College Diploma Bachelor Master Doctorate Other Government employee Private employee Student Other Less than 5 6-10 11-20 21-30 31-50 More than 50 Once a month Once a week Between 2 and 5 times a week Daily Other Recently (within the last 6 months) More than six month but less than a year More than one year but less than three years More than three years ago Other Number of respondents (n=464) Percentage (%) 202 262 0 177 201 56 28 2 9 69 267 88 2 29 137 146 5 176 144 202 73 25 10 10 4 10 27 422 1 210 34 76 140 4 43.53 56.47 0 38.15 43.32 12.07 6.03 0.43 1.94 14.87 57.54 18.97 0.43 6.25 29.53 31.47 1.08 37.93 31.03 43.53 15.73 5.39 2.16 2.16 0.86 2.16 5.82 90.95 0.22 45.26 7.33 16.38 30.17 0.86 4.3. Field Survey and the Measurement Scale Measurement items used in this study were either adapted from previously validated measures or developed based on the literature review. A seven-point likert scale ranging from (1) “strongly disagree” to (7) “strongly agree” was used to assess responses. Items from previous studies were modified for adaptation to the e-banking context. The final questionnaire items used to measure each construct are presented in Table 2. 7 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 Table 2: Summary of measurement scales used in the field survey Items Constructs 1 2 PU2 3 4 PU3 Perceived usefulness 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 PU1 PU4 PU5 PU6 PU7 PU8 PEOU1 PEOU2 Perceived PEOU3 ease of use PEOU4 PEOU5 PEOU6 TEB1 TEB2 Trust TEB3 TEB4 TEB5 ATU2 Attitude ATU3 towards ATU4 using ATU5 BI1 Behavioural BI2 intention to BI3 use BI4 Measures Using e-banking improves my performance of utilizing banking service. E-banking can enhance the effectiveness of customers’ transactions with bank Using e-banking services enables me to utilize banking service more quickly. Using e-banking for my banking service increases my productivity. I find e-banking useful for my banking activities Using e-banking makes it easier to do my banking activities Using e-banking can reduce queuing time Using e-banking can cut travelling expenses It is easy for me to become skillful at using the e-banking I find e-banking easy to do what I want to do It is easy for me to learn how to use e-banking I find e-banking to be flexible to interact with My interaction with e-banking is clear and understandable Overall, I find e-banking easy to use E-banking is trustworthy I trust in the benefits of the decisions of using e-banking E-banking keeps its promises and commitments E-banking would do the job right even if not monitored I trust e-banking Using e-banking is a wise idea Using e-banking is a pleasant idea Using e-banking is a positive idea Using e-banking is an appealing idea I intend to continue using e-banking in the future I expect my use of e-banking to continue in the future I will frequently use e-banking in the future I will strongly recommend others to use e-banking Notes: PU: Perceived Usefulness, PEOU: Perceived ease of use, TEB: Trust, ATU: Attitude Towards Using and BI: Behavioural Intention to use. 5. Empirical results 5.1 Exploratory factor analysis Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is a tool for assessing the factors that underlie a set of variables. It is frequently used to assess which items should be grouped together to form a scale and to reduce a large number of variables (items or indicators) into a smaller, manageable set of factors (Gerbing and Anderson, 1988; Hair, 2009). EFA is useful to detect the presence of meaningful patterns among the original variables and for extracting the main service factors (Lu et al., 2007). All items of the questionnaire were subjected to principal component analysis (PCA), an extraction method used to determine factors needed to represent the structure of the variables, using SPSS software version 20. The suitability of data for factor analysis was checked before the PCA was performed. Firstly, almost of each of all items was correlated (ρ≥0.3) with at least one other item, indicating reasonable factor analysis. Secondly, result of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) and the Barlett’s Test of Sphericity are shown in Table 3. 8 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 According to Tabachnick and Fidell (2007), KMO value is 0.6 or above and the Barlett’s Test of Sphericity value is significant, which should be 0.05 or smaller. It can be clearly seen that the KMO value is 0.945, and the Bartlett’s test is significant (p = 0.000) (Table 3). Finally, the communalities were all greater than 0.5 (see Table 4), providing additional evidence that each item shared some common variance with other items. Therefore, factor analysis is appropriate. Table 3: Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin and Bartlett's Test Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Measure of Sampling Adequacy. 0.945 Approx. Chi-Square Bartlett's Test of Sphericity df Sig. 10650.83 351 0.000 The principal component analysis revealed the presence of five components with eigenvalues exceeding 1.0, explaining 48.89%, 9.51%, 7.10%, 4.80%, and 3.82% of the variance respectively (Table 4). In conclusion, the five–component solution explained a total of 74.13% of the variance. Table 4: Total Variance Explained and Communalities Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings Commu % of Cumulative % of Cumulative nalities Total Total Variance % Variance % 1 13.2 48.891 48.891 13.2 48.891 48.891 0.711 2 2.567 9.507 58.398 2.567 9.507 58.398 0.816 3 1.918 7.105 65.503 1.918 7.105 65.503 0.778 4 1.298 4.806 70.309 1.298 4.806 70.309 0.682 5 1.031 3.817 74.126 1.031 3.817 74.126 0.775 6 0.658 2.438 76.564 0.800 7 0.633 2.344 78.908 0.551 8 0.585 2.165 81.072 0.683 9 0.563 2.085 83.158 0.759 10 0.412 1.526 84.684 0.743 11 0.4 1.483 86.168 0.767 12 0.382 1.416 87.584 0.776 13 0.339 1.255 88.839 0.701 14 0.327 1.212 90.051 0.656 15 0.308 1.14 91.191 0.813 16 0.292 1.083 92.274 0.689 17 0.259 0.959 93.233 0.730 18 0.242 0.898 94.13 0.527 19 0.234 0.866 94.996 0.799 20 0.215 0.797 95.793 0.759 21 0.21 0.777 96.57 0.833 22 0.188 0.696 97.267 0.772 23 0.179 0.663 97.93 0.856 24 0.164 0.607 98.537 0.811 25 0.144 0.535 99.072 0.830 26 0.132 0.488 99.56 0.825 27 0.119 0.44 100 0.572 Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Comp onent Initial Eigenvalues 9 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 The Pattern Matrix of the first factor analysis shows that all items have a factor loading greater than 0.5 while according to Hair and Black (2010) and Pallant (2007) the minimum suggested is 0.3 (Table 5). Thus, all items are valid to form five factors (latent variables): Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, Trust, Attitude towards Using, and Behavioural Intention to Use. Table 5: Pattern Matrix Component Variable PU5 PU6 PU4 PU3 PU7 PU8 PU2 PU1 PEOU3 PEOU2 PEOU1 PEOU6 PEOU5 PEOU4 TEB1 TEB5 TEB3 TEB2 TEB4 ATU5 ATU3 ATU2 ATU4 BI1 BI2 BI3 BI4 Perceived Usefulness Perceived Ease Of Use 0.931 0.887 0.865 0.819 0.805 0.772 0.737 0.595 -0.058 0.017 -0.055 0.073 0.136 0.119 -0.047 -0.067 -0.027 0.177 0.043 0.033 0.01 0.101 -0.115 0.059 0.032 0.01 -0.072 -0.032 -0.006 -0.041 0.083 0.066 0.035 0.007 0.068 0.953 0.903 0.857 0.813 0.725 0.715 -0.034 0.028 0.014 -0.072 0.136 -0.018 -0.029 -0.06 0.147 0.017 0.025 0.028 -0.11 Trust 0.013 0.064 0.065 0.006 -0.099 -0.139 0.071 0.001 -0.086 0.005 -0.005 0.079 0.108 0.046 0.937 0.904 0.853 0.68 0.68 0.025 0.003 0.006 -0.069 -0.049 -0.058 -0.008 0.275 Attitude Behavioural Towards Intention To Using Use 0.001 0.034 0.082 0.024 -0.076 -0.085 0.016 0.066 0.079 -0.016 -0.035 -0.012 -0.041 0.003 -0.039 -0.061 0.06 -0.023 0.051 0.959 0.94 0.761 0.752 -0.078 0.031 0.119 0.083 -0.075 -0.103 -0.104 -0.042 0.127 0.203 0.057 0.093 -0.063 -0.016 0.085 -0.016 0.026 -0.004 0.049 0.083 -0.042 0.156 -0.192 -0.092 -0.037 0.109 0.219 0.927 0.887 0.813 0.627 Notes: (1) Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis, (2) Rotation Method: Promax with Kaiser Normalization, (3) a. Rotation converged in 6 iterations. 5.2 Confirmatory factor analysis Following the result of the exploratory factor analysis, five factors were extracted from five groups of 27 items. Anderson and Gerbing (1988), Lomax and Schumacker (2012), and Hair and Black (2010) suggested that the data analysis employed a two-phase approach in order to evaluate the reliability and validity of the measures before using them in the 10 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 research model. The first phase analyses the measurement model; the second phase tests the structural relationships among latent constructs. The test of the measurement model, which indicates the strength measures used to test the research model, involves the estimation of internal consistency reliability as well as the convergent and discriminate validity of the research instruments (Fronell, 1982). The structural equation models were then examined for hypotheses testing. Both the measurement models and the structural models were evaluated by the maximum likelihood method using AMOS 20 software, distributed by SPSS software version 20. Internal consistency reliability is a statement about the stability of individual measurement items across replications from the same source of information (Straub, 1989). Internal consistency was evaluated by computing Cronbach’s alpha. The alpha coefficients for each construct of this study are presented in Table 6. Hair (2010) suggested that the lowest limit for Cronbach’s alpha be 0.70, while Straub (1989) suggested 0.80 as the limit. All constructs in the research model have acceptable reliability because the construct with the lowest alpha coefficient showed marginally satisfactory reliability. The corrected item-total correlation values are given in Table 6. These values show the correlation between individual items and the total score (Pallant, 2007; Tabachnick and Field, 2007). If the Corrected item-total correlation value is below 0.3, this mean that this item measures another characteristic other than the overall characteristics of the group of items. In this study all corrected item-total correlation values are above 0.5. The alpha score if each item is deleted is also provided in Table 6. If deleting an item results in an increase in the alpha score, then the item should be removed (Pallant, 2007). Two items fit this classification: TEB4 in Trust in e-banking (from 0.886 to 0.900) and BI4 in Behavioural intention to use (from 0.879 to 0.912) (Table 6). As the differences in these cases are rather small, these items were not deleted. Therefore, it can be concluded that the levels of internal consistency among the five groups of items were different but they were valid for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). 11 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 Table 6: Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency checking Factor Perceived Usefulness Perceived Ease of Use Trust in ebanking Attitude towards using Behavioural intention to use Item Mean Standard deviation Corrected item-total correlation PU1 PU2 PU3 PU4 PU5 PU6 PU7 PU8 PEOU1 PEOU2 PEOU3 PEOU4 PEOU5 PEOU6 TEB1 TEB2 TEB3 TEB4 TEB5 ATT2 ATT3 ATT4 ATT5 BI1 BI2 BI3 BI4 5.86 5.95 6.02 5.91 6.01 5.89 6.12 6.22 5.63 5.71 5.68 5.75 5.78 5.78 5.41 5.71 5.54 5.34 5.54 5.88 5.75 5.97 5.78 6.11 6.09 6.06 5.75 0.927 0.810 0.858 0.868 0.843 0.866 0.851 0.817 1.161 1.052 1.063 1.029 0.904 0.946 1.064 0.880 0.945 1.167 0.991 0.853 0.913 0.820 0.909 0.750 0.755 0.747 0.934 0.683 0.782 0.821 0.799 0.809 0.821 0.771 0.728 0.759 0.852 0.794 0.761 0.821 0.842 0.805 0.716 0.752 0.587 0.805 0.779 0.821 0.777 0.839 0.769 0.813 0.818 0.602 Cronbach's Alpha 0.936 0.932 0.886 0.914 0.879 Cronbach's Alpha if Item Deleted 0.935 0.927 0.924 0.926 0.925 0.924 0.928 0.931 0.927 0.913 0.920 0.924 0.918 0.915 0.841 0.865 0.856 0.900 0.843 0.896 0.882 0.897 0.875 0.835 0.818 0.816 0.912 The level of internal consistency of the items in each of the five groups was verified, so simple confirmatory factor analyses would be carried out on each group of items to extract the corresponding latent variables. The values of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) are all greater than 0.6 and the Barllett’s Test of Sphericity is significant with p = 0.000. All five factors analyses are therefore appropriate (Pallant, 2007; Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007) (Table 7). Furthermore, all items were loaded quite strongly. As a result, the five factors extracted from five groups of items are appropriate for further use in data processing. 12 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 Table 7: Simple confirmatory factor analyses for 5 latent variables Factor Perceived Usefulness Perceived Ease of Use Trust in ebanking Attitude towards using Behavioural intention to use Communialities Item loading KMO = 0.921***. Total of initial Eigenvalues = 5.557ª. Percentage of variance = 69.463 PU1 0.566 0.752 PU2 0.694 0.833 PU3 0.756 0.870 PU4 0.727 0.852 PU5 0.742 0.862 PU6 0.759 0.871 PU7 0.686 0.828 PU8 0.626 0.791 KMO = 0.897***. Total of initial Eigenvalues = 4.524ª. Percentage of variance = 75.401 PEOU1 0.689 0.901 PEOU2 0.812 0.898 PEOU3 0.738 0.884 PEOU4 0.698 0.859 PEOU5 0.782 0.835 PEOU6 0.806 0.830 KMO = 0.877***. Total of initial Eigenvalues = 3.502ª. Percentage of variance = 70.048 TEB1 0.797 0.893 TEB2 0.686 0.888 TEB3 0.724 0.851 TEB4 0.506 0.828 TEB5 0.788 0.712 KMO = 0.831***. Total of initial Eigenvalues = 3.18ª. Percentage of variance = 79.498 ATT2 0.767 0.914 ATT3 0.813 0.902 ATT4 0.765 0.876 ATT5 0.835 0.875 KMO = 0.801***. Total of initial Eigenvalues = 3.012ª. Percentage of variance = 75.295 BI1 0.790 0.915 BI2 0.836 0.908 BI3 0.825 0.889 BI4 0.561 0.749 Notes: ***. Significant at 0.01 level. ª. One component was extracted 5.3 Factor-of-factor analysis In order to evaluate the five latent variables, a factor-of-factor analysis was carried out. Before conducting a confirmatory factor analysis, the level of internal consistency of the items was verified, as shown in Table 8. All corrected item-total correlations are greater than 0.6, indicating relatively high correlation among items in the groups (Pallant, 2007; Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007) (Table 8). The Alpha score 0.846 is greater than the limitation of 0.7 (Hair, 2010). As a result, the group is considered appropriate for confirmatory factor analysis. Table 9 indicates that the score of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) is 0.814, which is greater than the suggested minimum score of 0.6 (Pallant, 2007; Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007); the Barllett’s Test of Sphericity is significant with p = 0.000. The factor loading values are mostly greater than 0.7 and are considered very high (Pallant, 2007; Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007). 13 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 Table 8: Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency checking of 5 latent variables Corrected itemtotal correlation Factor Perceived Usefulness Perceived Ease Of Use Trust in e-banking Attitude Towards Using Behavioural Intention To Use Cronbach's Alpha 0.750 0.629 0.602 0.631 0.661 Alpha if item is deleted 0.789 0.822 0.829 0.821 0.813 0.846 Table 9: Factor analysis of Structural Model Item Communalities Factor loading KMO = 0.814***. Total of initial Eigenvalues = 3.104ª. Percentage of variance = 62.078. P-value=0.000 Perceived Ease Of Use 0.736 0.770 Perceived Usefulness 0.593 0.858 Trust in e-banking 0.554 0.745 Attitude Towards Using 0.591 0.769 Behavioural Intention To Use 0.629 0.793 Notes: ***. Significant at 0.01 level; ª. One component was extracted As a result, the factor extracted from the five latent variables is appropriate. This factor is called the Structural Model. CFA was used to examine the convergent validity of each construct. A single factor model for each of the constructs was specified and presented in Table 9. Table 9 also showed the factor loadings of the measurement items: all items passed the recommended level for factor loading of 0.6 (Chin et al., 1997). Table 10 shows the overall model-fit indices for each CFA model as recommended by Kline (2011). Most indices passed the recommended level, suggesting that the items of each construct reflect a single factor (Table 10). According to Fornell and Larcker (1981) and Chin (1998), the requirement of discriminant validity is satisfied when the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of the construct is larger than all pair square correlations between the construct and other constructs in the model. Table 10: Overall model fit indices of CFA for convergent validity Construct Chisquar e d.f Recommended Value Perceived Usefulness Perceived Ease of Use 46.05 1 16.10 2 17 6 Trust in e-banking 8.180 5 Attitude towards using 0.927 1 Behavioural intention to use 0.143 1 𝜒 ₂ /df < 3.0 2.70 9 2.68 4 1.63 6 0.92 7 0.14 3 GFI AGFI NFI TLI CFI RMSEA PCLOS E > 0.9 0.97 5 0.98 9 0.99 3 0.99 9 1.00 0 > 0.8 > 0.9 0.98 4 0.99 3 0.99 4 0.99 9 1.00 0 > 0.9 0.98 4 0.98 9 0.99 5 1.00 0 1.00 4 > 0.9 < 0.08 > 0.05 0.990 0.061 0.182 0.996 0.06 0.272 0.998 0.037 0.626 1.000 0.000 0.566 1.000 0.000 0.831 0.946 0.961 0.979 0.990 0.998 Note: GFI: Goodness of Fit Index, AGFI: adjusted goodness of fit index, NFI: normed fit index, TLI: Tucker-Lewis Index, CFI: comparative fit index, RMSEA: root mean square error of approximation, PCLOSE is an alternative test of hypothesis that RMSEA is less than or equal to 0.05. As shown in Table 11, the diagonal elements (in bold) are the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE), and off-diagonal elements are the correlations among constructs. For discriminant validity, the diagonal elements should be larger than the off14 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 diagonal elements. As a result, all indicators load more highly on their own constructs than on other constructs. All these results point to the discriminant validity of the constructs. Table 11: Discriminant validity of constructs Attitude Towards Using Attitude Towards Using 0.825 Perceived Usefulness Perceived Ease Of Use Trust in EBanking Perceived Usefulness 0.633 0.808 Perceived Ease Of Use 0.505 0.772 0.840 Trust in E-Banking Behavioural Intention to use 0.530 0.602 0.568 0.796 0.758 0.642 0.518 0.523 Behavioural Intention to use 0.827 5.4 Normality distribution The assessment method suggested by Hair et al. (2010) proves the violation of normality. Nevertheless, taking into consideration these acceptable values of skewness and kurtosis, and that the sample size was significantly larger than 200 (in this study, sample = 464 participants), the influence of this assumption violation on the results of the parametric analysis would be minimal (Curran et al., 1996; Mendenhall et al., 2012; Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007). Furthermore, Shah and Goldstein (2006) and Jöreskog and Sörbom (1993) suggested that non-normality can be tolerable when the SEM Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation technique is used. Therefore, violation of the normality assumption was considered to be at an acceptable level for the parametric statistical method (Byrne, 2013; Curran et al., 1996; Mendenhall et al., 2012). 5.5 The final measurement model After CFA was conducted for each construct, the whole measurement model was subjected to CFA to test the discriminant validity and to evaluate the overall fit (as reported). In the overall measurement model, all constructs are free to correlate with others. The relationships among latent variables are depicted in the overall measurement model shown in Figure 3. The five latent variables were measured by respective items. These latent variables can correlate with each other. The selected fit indices of this model (chisquare/df = 2.38, GFI = 0.897, TLI = 0.954, CFI = 0.960, RMSEA = 0.055, PCLOSE = 0.073) indicate that this model has achieved a very good fit. The correlation coefficients among constructs are provided to evaluate multi-collinearity (see Table 12). According to Hair et al. (2010) and Kline (2011), variables highly correlated with each other (i.e., 0.8 and above) indicate the problem of multi-collinearity. None of these constructs in this study are too highly correlated with each other in each model, as the highest correlation was 0.772 between Perceived Ease of Use and Perceived Usefulness. Therefore, the level of multi-collinearity was considered to be acceptable. 15 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 Figure 3: Structure of the model and inter-relationships among latent variables 5.6 The final structural model The structural model identifies the relationship among latent variables. It then investigates the way by which certain latent variables directly or indirectly influence other latent variables (Byrne, 2013). In line with the hypotheses, the second step of the analysis relates to constructing structural models. After assessing the reliability and validity with CFA, we test the structural model fit. The overall model fit evaluates the correspondence of the actual or observed input matrix with that predicted from the propose model. Table 12 shows a summary of the overall fit indices of the path model. 16 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 Table 12: Structural model fit indices Construct Chisquare df 𝜒 ₂ /df GFI AGFI NFI TLI CFI RMSEA PCLOSE Recommended < > 0.8 > 0.8 > 0.9 > 0.9 > 0.9 < 0.08 > 0.05 Value 3.0 Structural Model 720.001 303 2.38 0.897 0.871 0.934 0.954 0.96 0.055 0.073 Note: GFI: Goodness of Fit Index, AGFI: adjusted goodness of fit index, NFI: normed fit index, TLI: TuckerLewis Index, CFI: comparative fit index, RMSEA: root mean square error of approximation, PCLOSE is an alternative test of hypothesis that RMSEA is less than or equal to 0.05. Most indices passed the recommended level. The indices of this model indicate that this model achieved a very good fit (Table 12). The structural model specifies the relationships among latent variables. All the path coefficients of the structural model are standardized; the square multiple correlation (analogous to R2 in linear regression analysis) of each dependent latent variable was also depicted (Figure 4). The results from the structural model in Table 13 are used to test the hypotheses (from H1 to H9). Table 13: Standardized regression weights (SRW) Behavioural relationship Hypothesis SRW Pvalue Behavioural_Intention_to_Use ← Trust H1 0.093 0.051 Attitude_towards_Using ← Trust H2 0.242 *** Trust ← Perceived_Usefulness H3 0.418 *** Attitude_towards_Using ← Perceived_Usefulness H4 0.513 *** Behavioural_Intention_to_Use ← Perceived_Usefulness H5 0.186 0.008 Trust ← Perceived_Ease_of_Use H6 0.241 *** Attitude_towards_Using ← Perceived_Ease_of_Use H7 0.047 0.523 Perceived_Usefulness ← Perceived_Ease_of_Use H8 0.779 *** Behavioural_Intention_to_Use ← Attitude_towards_Using H9 0.609 *** Note: *** indicates p<0.001 17 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 Figure 4: Result of structural analysis: primary model 5.7 Hypotheses testing H1: Trust has a positive effect on the behavioural intention to use e-banking. H2: Trust has a positive impact on the attitude towards using e-banking. The results presented in Figure 4 and Table 13 indicate that the relationship between Trust and Behavioural intention to use is positive (standardized regression weight = 0.093) and significant (at 5% level of significant), thereby Hypothesis 1 is supported. Moreover, the relationship between Trust and Attitude towards using is positive and significant (standardized regression weight = 0.242, p<0.001) as reported in Table 13. Thus, hypothesis 2 is supported. These findings are also consistent with the previous study by Suh and Han (2002). H3: Perceived usefulness has a positive impact on trust in e-banking. H4: Perceived usefulness has a positive impact on the attitude towards using e-banking. H5: Perceived usefulness has a positive impact on the behavioural intention to use ebanking. The relationship between Perceived usefulness and Trust is positive and significant (standardized regression weight = 0.418, p<0.001), providing support for Hypothesis 3 18 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 (Table 13). Accordingly, hypothesis 4 suggested that perceived usefulness has a positive impact on the attitude towards using e-banking. The results in Table 13 indicate that perceived usefulness is positive, in the relation with attitude towards using, and significant (standardized regression weight = 0.513, p<0.001), thus, hypothesis 4 is supported. This finding is also consistent with the previous study by Çelik (2008). Moreover, perceived usefulness has a positive effect on the behavioural intention to use e-banking and is significant with standardized regression weight = 0.186, p<0.05; thus hypothesis 5 is supported (Table 13). This finding is not consistent with the previous study by Kasheir et al. (2009), which found that perceived usefulness did not have any significant effect on customers’ behavioural intention to use e-banking. H6: Perceived ease of use has a positive impact on trust in e-banking. H7: Perceived ease of use has a positive impact on the attitude towards using e-banking. H8: Perceived ease of use has a positive impact on perceived usefulness. The results show that perceived ease of use has a positive effect and is significant on trust in e-banking (standardized regression weight = 0.241, p<0.001), providing strong evidence to support hypothesis 6 (Table 13). Interestingly, perceived ease of use was a negative relationship and has no significant influence on the attitude towards using e-banking (standardized regression weight = -0.047, p<0.523). Thus, hypothesis 7 that perceived ease of use has a positive impact on the attitude towards using e-banking is not supported. This finding is in contrast with the previous studies by Suh and Han (2002), Amin (2007), Çelik (2008), and Jahangir and Begum (2008) that perceived ease of use directly affects customer attitude towards using e-banking. Moreover, this result also contradicts the original TAM models. On the other hand, it is consistent with the finding of Pikkarainen et al. (2004), which suggested that there is no significant impact of perceived ease of use on customer intention to use e-banking. However, perceived ease of use has a positive effect and is significant with perceived usefulness (standardized regression weight = 0.779, p<0.001), providing strong evidence to support hypothesis 8. This finding is consistent with findings by Suh and Han (2002) that a customers’ perceived ease of use has a positive impact on his/her perceived usefulness of e-banking. H9: Attitude towards using has a positive impact on the behavioural intention to use ebanking. Hypothesis 9 suggested that there is a positive relationship between the attitude towards using and behavioural intention to use e-banking. The result seen in Table 13 shows that the attitude towards using has a positive impact on the behavioural intention to use ebanking and is significant (standardized regression weight = 0.609, p<0.001), thus, hypothesis 9 is supported. This finding is consistent with findings by Shih and Fang (2006), who concluded that the attitude towards using e-banking is significantly related to the behavioural intention to use e-banking. In the data analysis used to test the hypotheses, SEM using two-step approach was applied. First, measurement models were tested to measure the reliability and validity of the latent variables (perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, trust, attitude towards using, and behavioural intention to use). Structural models were then developed to evaluate the relationships among those latent variables. The results provided support for all the hypotheses, except for H7 (Table 14). The trust has significant effects on both attitude and behavioural intention to use e-banking. The 19 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 perceived usefulness has positive significant impact on trust in, attitude towards and the behavioural intention to use e-banking. The perceived ease of use has positive significant effect on trust and perceived usefulness. However, perceived ease of use does not have significant effect on the attitude towards using e-banking. Attitude towards using e-banking has positive impact on the behavioural intention to use e-banking. Table 14: Summarized results of hypotheses testing Hypotheses Statement P-value Results H1 Trust has a positive effect on the behavioural intention to use ebanking. 0.051 Supported H2 Trust has a positive impact on the attitude towards using e-banking. *** Supported H3 Perceived usefulness has a positive impact on trust in e-banking. *** Supported H4 Perceived usefulness has a positive impact on the attitude towards using e-banking. *** Supported H5 Perceived usefulness has a positive impact on the behavioural intention to use e-banking. 0.008 Supported H6 Perceived ease of use has a positive impact on trust in e-banking. *** Supported 0.523 Not supported *** Supported *** Supported H7 H8 H9 Perceived ease of use has a positive impact on the attitude towards using e-banking. Perceived ease of use has a positive impact on perceived usefulness. Attitude towards using e-banking has a positive impact on the behavioural intention to use e-banking. Note: *** indicates p<0.001 6. Conclusion This study has discovered that the trust is one of the most significant factors in explaining customer intention to use e-banking. According to Davis (1989), the TAM suggested that customers’ perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use also affect their attitude towards using significantly. Then, behavioural intention to use e-banking is highly related to attitude towards using, perceived usefulness, and trust. However, the results in this study show that customers’ perceived usefulness is highly related to attitude towards using, while customers’ perceived ease of use has not affected attitude towards using. Overall, these results imply that customers in online environments still rely on trust that their sensitive information is being processed. In the online environment, trust plays an important role in financial transactions. This study has extended the TAM by added an additional belief, trust, one of the most important determinants of customer intention to use e-banking. This model is tested empirically to explain customer intention to use e-banking in Vietnam. These results give a better understanding of the factors affecting customers’ behavioural intention to use e-banking in a developing country like Vietnam. In comparison with other countries, Vietnamese customers might have different cultures, so it is important to consider whether trust will affect their intention to use e-banking. These results will benefit practitioners, e-banking system developers, bank decision makers and bank service providers. Bank managers and decision makers in Vietnam can 20 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 use these findings when making their strategies and plans for future development. It is suggested that banks should focus on improving their e-banking websites to be more and more friendly and attractive, but the perceived usefulness of e-banking is more important than the perceived ease of use. Banks should also further explore what features are useful to the Vietnamese customers, then design the e-banking website’s characteristic based on these features. Through education, banks can show the advantages of e-banking to customers and more useful features should be investigated to attract more e-banking customers. Trust is one of the most important factors affecting customer intention to use ebanking in Vietnam, so banks in Vietnam should ensure that security and privacy of ebanking systems are regularly upgraded, while customers should be advised that their systems are secure and personal information is absolutely protected. There are several limitations in this study. First, as in previous studies, the selected model and factors may not cover all the reasons that could affect customers’ intention to use ebanking in Vietnam. Therefore, future research needs to explore other models and factors related to cultural issues or consumers’ habits which may have influences to the intention to use e-banking. Second, this study is based on customer experience in using e-banking to answer the questionnaire survey to collect data for analysis. Future research analysis can be based on a demographic profile such as age group, income, or level of education. For example, customers in an older age group might find it more of a challenge to use ebanking transactions, thus perceived ease of use might be one important factor affecting customer intention to use e-banking. Third, this study was conducted with Vietnamese customers in a developing country like Vietnam, so all ideas reflect the Vietnamese perspective. Future study can apply the model used in this study to other developing countries. Lastly, data for this research was collected in selected provinces in Vietnam, so the results might have not covered other provinces because of the difference between area cultural issues. Future research can collect data in many more areas and provinces in order to reflect more generally the customer intention to use e-banking in Vietnam. References ABDULLAHAL-SOMALI, S., ROYAGHOLAMI & BENCLEGG 2009. An investigation into the acceptance of onlinebanking in Saudi Arabia. Technovation, 29, 130–141. AJZEN, I. & FISHBEIN, M. 1980. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour, Prentice-Hall. ALAIN YEE-LOONG CHONG, KENG-BOON OOI, BINSHAN LIN & TAN, B.-I. 2010. Online banking adoption: an empirical analysis. International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 28, pp.267 - 287. ALDÁS-MANZANO, J., LASSALA-NAVARRÉ, C., RUIZ-MAFÉ, C. & SANZ-BLAS, S. 2009. Key drivers of internet banking services use. Online Information Review, Vol. 33, pp.672 - 695. ALSAJJAN, B. A. & DENNIS, C. 2006. The Impact of Trust on Acceptance of Online Banking. European Association of Education and Research in Commercial Distribution. AMIN, H. 2007. Internet Banking Adoption Among Young Intellectuals. Journal of Internet Banking & Commerce, 12. ANDERSON, J. C. & GERBING, D. W. 1988. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological bulletin, 103, 411. ANITA LIFEN ZHAO, NICOLE KOENIG-LEWIS, STUART HANMER-LLOYD & WARD, P. 2010. Adoption of internet banking services in China: is it all about trust? International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 28, pp. 7 - 26. BA, S. & PAVLOU, P. A. 2002. Evidence of the effect of trust building technology in electronic markets: Price premiums and buyer behaviour. MIS Quarterly, 243-268. 21 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 BENAMATI, J. S. & SERVA, M. A. 2007. Trust and distrust in online banking: Their role in developing countries. Information Technology for Development, Volume 13, pages 161– 175. BYRNE, B. M. 2013. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming, Routledge. CASALÓ, L. V., FLAVIÁN, C. & GUINALÍU, M. 2007. The role of security, privacy, usability and reputation in the development of online banking. Online Information Review, 31, 583-603. ÇELIK, H. 2008. What determines Turkish customers' acceptance of internet banking? International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 26, pp.353 - 370. CHANG, C., LEE, A. C. & LEE, C. F. 2009. Determinants of capital structure choice: A structural equation modeling approach. The quarterly review of economics and finance, 49, 197-213. CHIEMEKE, S. C., EVWIEKPAEFE, A. E. & CHETE, F. O. 2006. The Adoption of Internet Banking in Nigeria: An Empirical Investigation. Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce, vol. 11, no.3. CHIN, W. W. 1998. Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. JSTOR. CHIN, W. W., GOPAL, A. & SALISBURY, W. D. 1997. Advancing the theory of adaptive structuration: The development of a scale to measure faithfulness of appropriation. Information systems research, 8, 342-367. CURRAN, P. J., WEST, S. G. & FINCH, J. F. 1996. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological methods, 1, 16. DAVIS, F. D. 1989. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 319-340. DAVIS, F. D., BAGOZZI, R. P. & WARSHAW, P. R. 1989. User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Management Science, 35, 9821003. DIXIT, N. & DATTA, S. K. 2010. Acceptance of E-banking among Adult Customers: An Empirical Investigation in India. Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce, vol. 15, no.2. DONEY, P. M. & CANNON, J. P. 1997. An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. the journal of marketing, 35-51. FORNELL, C. & LARCKER, D. F. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research (JMR), 18. FRONELL, C. 1982. A second generation of multivariate analysis. Methods, New York, Praeger, 1. GEFEN, D. 2000. E-commerce: the role of familiarity and trust. Omega, 28, 725-737. GRABNER-KR.AUTERA, S. & KALUSCHA, E. A. 2003. Empirical research in on-linetrust: a review and critical assessment. Int. J. Human-Computer Studies, 58, 783–812. GRABNER-KRÄUTER, S. & FAULLANT, R. 2008. Consumer acceptance of internet banking: the influence of internet trust. International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 26, pp.483 - 504. HAIR, J. & BLACK, W. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. HAIR, J. F. 2009. Multivariate data analysis. HOY, W. K. & TARTER, C. J. 2004. Organizational justice in schools: no justice without trust. International Journal of Educational Management, 18, 250-259. HOYLE, R. H. 1995. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications, Sage. JAHANGIR, N. & BEGUM, N. 2008. The role of perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, security and privacy, and customer attitude to engender customer adaptation in the context of e-banking. African Journal of Business Management, 2, 32-40. JÖRESKOG, K. G. & SÖRBOM, D. 1993. Lisrel 8: Structured equation modeling with the Simplis command language, Scientific Software International. KASHEIR, D. E.-., ASHOUR, A. S. & YACOUT, O. M. 2009. Factors Affecting Continued Usage of Internet Banking Among Egyptian Customers. Communications of the IBIMA, Vol 9, 252263. KASSIM, N. M. & ABDULLA, A. K. M. A. 2006. The influence of attraction on internet banking: an extension to the trust-relationship commitment model. International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 24, pp.424 - 442. KHALIL MD NOR, JANEJIRA SUTANONPAIBOON & MASTOR, N. H. 2010. Malay, Chinese, and internet banking. Chinese Management Studies, Vol. 4, pp.141 - 153. 22 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 KLINE, R. B. 2011. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, Guilford press. KOUFARIS, M. & HAMPTON-SOSA, W. 2004. The development of initial trust in an online company by new customers. Information & Management, 41, 377-397. LICHTENSTEIN, S. & WILLIAMSON, K. 2006. Understanding consumer adoption of internet banking: an interpretive study in the Australian banking context. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 7, 50-66. LIMBU, Y. B., WOLF, M. & LUNSFORD, D. 2012. Perceived ethics of online retailers and consumer behavioural intentions: The mediating roles of trust and attitude. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 6, 133-154. LIU, T.-C. & WU, L.-W. 2007. Customer retention and cross-buying in the banking industry: an integration of service attributes, satisfaction and trust. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 12, 132-145. LOMAX, R. G. & SCHUMACKER, R. 2012. A beginner's guide to structural equation modeling, Routledge Academic. LU, C.-S., LAI, K.-H. & CHENG, T. E. 2007. Application of structural equation modeling to evaluate the intention of shippers to use Internet services in liner shipping. European Journal of Operational Research, 180, 845-867. MACINTOSH, G. & LOCKSHIN, L. S. 1997. Retail relationships and store loyalty: a multi-level perspective. International Journal of Research in marketing, 14, 487-497. MAYER, R. C., DAVIS, J. H. & SCHOORMAN, F. D. 1995. An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of management review, 709-734. MCKNIGHT, D. H., CHOUDHURY, V. & KACMAR, C. 2002. Developing and validating trust measures for e-commerce: An integrative typology. Information systems research, 13, 334359. MENDENHALL, W., BEAVER, R. & BEAVER, B. 2012. Introduction to probability and statistics, Cengage Learning. MORGAN, R. M. & HUNT, S. D. 1994. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. the journal of marketing, 20-38. MUÑOZ-LEIVA, F., LUQUE-MARTÍNEZ, T. & SÁNCHEZ-FERNÁNDEZ, J. 2010. How to improve trust toward e-banking. Online Information Review, Vol. 34, pp.907 - 934. NDUBISI, N. O. & SINTI, Q. 2006. Consumer attitudes, system's characteristics and internet banking adoption in Malaysia. Management Research News, Vol. 29, pp. 16 - 27. PALLANT, J. 2007. A step-by-step guide to data analysis using SPSS version 15. Open University Press, Maidenhead. PALMER, A. & BEJOU, D. 1994. Buyer‐seller relationships: A conceptual model and empirical investigation. Journal of Marketing Management, 10, 495-512. PIKKARAINEN, T., PIKKARAINEN, K., KARJALUOTO, H. & PAHNILA, S. 2004. Consumer acceptance of online banking: an extension of the technology acceptance model. Emerald 14. PLOUFFE, C. R., VANDENBOSCH, M. & HULLAND, J. 2001. Intermediating technologies and multi‐group adoption: A comparison of consumer and merchant adoption intentions toward a new electronic payment system. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 18, 65-81. RATNASINGHAM, P. 1998. The importance of trust in electronic commerce. Internet Research, 8, 313-321. ROUSSEAU, D. M., SITKIN, S. B., BURT, R. S. & CAMERER, C. 1998. Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of management review, 23, 393-404. SATHYE, M. 1999. Adoption of Internet banking by Australian consumers: an empirical investigation. International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 17, pp. 324 - 334. SHAH, R. & GOLDSTEIN, S. M. 2006. Use of structural equation modeling in operations management research: Looking back and forward. Journal of Operations Management, 24, 148-169. SHIH, Y.-Y. & FANG, K. 2006. Effects of network quality attributes on customer adoption intentions of Internet Banking. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 17:1, 61-77. SHUMAILA Y. YOUSAFZAI, JOHN G. PALLISTER & FOXALL, G. R. 2003. A proposed model of e-trust for e-banking. Technovation, 23, 847–860. 23 Proceedings of Global Business and Finance Research Conference 5-6 May, 2014, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-50-4 SMITH, P. A. & BIRNEY, L. L. 2005. The organizational trust of elementary schools and dimensions of student bullying. International Journal of Educational Management, 19, 469485. STRAUB, D. W. 1989. Validating instruments in MIS research. MIS Quarterly, 147-169. SUH, B. & HAN, I. 2002. Effect of trust on customer acceptance of Internet banking. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 1, pp 247–263. TABACHNICK, B. & FIDELL 2007. Using multivariate statistics. 5. TAN, M. & TEO, T. S. H. 2000. Factors Influencing the Adoption of Internet Banking. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, Volume 1. TITMAN, S. & WESSELS, R. 1988. The determinants of capital structure choice. The Journal of Finance, 43, 1-19. VATANASOMBUT, B., IGBARIA, M., STYLIANOU, A. C. & RODGERS, W. 2008. Information systems continuance intention of web-based applications customers: The case of online banking. Information & Management, 45, 419-428. WAN, W. W. N., LUK, C.-L. & CHOW, C. W. C. 2005. Customers' adoption of banking channels in Hong Kong. International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 23, pp.255 - 272. WANG, A. 2010. THE PRACTICES OF MOBILE ADVERTISING DISCLOSURE ON CONSUMER TRUST AND ATTITUDE. International Journal of Mobile Marketing, 5. WANG, J.-S. & PHO, T.-S. 2009. Drivers of customer intention to use online banking: An empirical study. African Journal of Business Management, Vol.3 (11), pp. 669-677. WHITENER, E. M., BRODT, S. E., KORSGAARD, M. A. & WERNER, J. M. 1998. Managers as initiators of trust: An exchange relationship framework for understanding managerial trustworthy behaviour. Academy of management review, 23, 513-530. WONG, D. H., LOH, C., YAP, K. B. & BAK, R. 2009. To Trust or Not to Trust: The Consumer’s Dilemma with E-banking. Journal of Internet Business, pp 1-27. 24