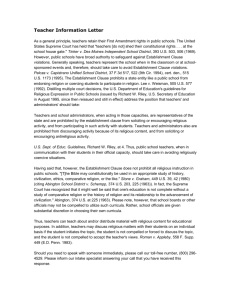

Evaluating the Supreme Court’s Establishment Clause Jurisprudence in the County v. ACLU

advertisement