No “Free Pass” for Employees: Missouri Missouri Human Rights Act

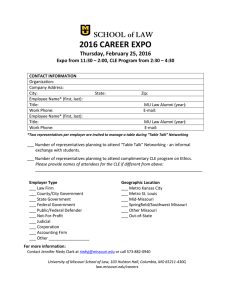

advertisement

No “Free Pass” for Employees: Missouri Says “Yes” to Individual Liability Under the Missouri Human Rights Act I. INTRODUCTION For over a decade, Missouri federal courts have debated the interpretation of the term “employer” provided in the Missouri Human Rights Act (“MHRA”), offering two distinct interpretations. Some have held that the MHRA’s definition of “employer” allows for individual liability for managers and supervisors along with the employing entity. 1 However, recent Missouri federal opinions have reluctantly followed Eighth Circuit precedent in holding that the MHRA does not impose individual liability. 2 Amid the conflicting federal judicial decisions, one thing has remained constant: every Missouri federal court has tried to predict how the Missouri Supreme Court would decide the issue. 3 As a result of binding precedent on recent Missouri federal court decisions, Missouri federal courts have ruled against the more logical and just interpretation of “employer” within the MHRA. Consequently, the underlying purpose of the MHRA has been undermined by failing to provide victims of employment discrimination with sufficient compensation and personal vindication for their injuries. However, a recent decision by the Missouri Court of Appeals for the Eastern District rejecting the established federal law may end the inconsistency within the Missouri federal courts and may finally lead to justice for victims of employment discrimination. 4 Missouri state and federal courts will no longer be forced under the doctrine of stare decisis to allow individual wrongdoers a “free pass” to discriminate, thus depriving victims of employment discrimination of their right to just compensation and 1. See, e.g., Wesley v. OCE Bus. Servs., Inc., No. 05-0055CVWSOW, 2005 WL 998624 (W.D. Mo. Apr. 19, 2005); Hill v. Ford Motor Co., 324 F. Supp. 2d 1028 (E.D. Mo. 2004); Shortey v. U.S. Bank, N.A., No. 03-0530-CV-W-SWH, 2003 WL 24225868 (W.D. Mo. Dec. 5, 2003). 2. See, e.g., Smith v. Schnuck Markets, Inc., No. 4:04CV711 JCH, 2006 WL 1790162, at *5 (E.D. Mo. June 27, 2006); Walker v. Lanoga Corp., No. 06-0148-CVW-FJG, 2006 WL 1594451, at *4 (W.D. Mo. June 9, 2006); Widmar v. City of Kansas City, Mo., No. 05-0599-CV-W-DW, 2006 WL 743171, at *2 (W.D. Mo. Mar. 20, 2006); Baines v. Mo. Gaming Co., No. 05-6031-CV-SJ-FJG, 2006 WL 506184, at *2 (W.D. Mo. Feb. 28, 2006). These recent Missouri federal courts have followed the decision in Lenhardt v. Basic Institute of Technology, 55 F.3d 377 (8th Cir. 1995) (holding that the Missouri Supreme Court would not interpret the MHRA as imposing individual liability). 3. See Lenhardt, 55 F.3d at 379. 4. Cooper v. Albacore Holdings, Inc., 204 S.W.3d 238 (Mo. Ct. App. 2006). 130 948 MISSOURI LAW REVIEW [Vol. 72 personal redress during a time in which employee discrimination is of widespread concern throughout Missouri and nationwide. II. LEGAL BACKGROUND Missouri federal courts have questioned individual liability under the MHRA since the Act’s passage. To help fully understand the confusion over the interpretation of the MHRA, the following sections provide an overview of the Act’s applicable provisions, along with significant court decisions interpreting the MHRA and analogous statutes. A. Applicable Provisions of the MHRA Under the MHRA, it is unlawful for an employer to “discriminate against any individual . . . because of such individual’s race, color, religion, national origin, sex, ancestry, age or disability.” 5 The statute only applies to employers. 6 Accordingly, a defendant may not be liable under Missouri Revised Statute section 213.055.1(1)(a) unless the defendant is considered an “employer” as defined within the MHRA. 7 The MHRA provides in relevant part that an employer is “any person employing six or more persons within the state, and any person directly acting in the interest of an employer.” 8 The language, “any person directly acting in the interest of an employer,” has created uncertainty as to whether the statute provides for individual liability. B. Individual Liability under the MHRA In interpreting the MHRA, some Missouri federal courts hold that employers are subject to individual liability under the Act, 9 while others have determined that the MHRA establishes only respondeat superior liability. 10 In addition, at least one federal court has refused to decide the issue, leaving 5. MO. REV. STAT. § 213.055.1(1)(a) (2000). 6. See id. § 213.055.1(1). 7. See, e.g., Lenhardt, 55 F.3d at 379. 8. MO. REV. STAT. § 213.010(7) (2000) (emphasis added). 9. See supra note 1 and accompanying text. 10. See, e.g., Lenhardt, 55 F.3d 377; Klotz v. CorVel Healthcare Corp., No. 4:05 CV 1034 CAS, 2005 WL 3008515, at *3 (E.D. Mo. Nov. 9, 2005); Weger v. City of Ladue, No. 4:04CV00683SNL, 2004 WL 3651669 (E.D. Mo. Dec. 30, 2004). Respondeat superior is “[t]he doctrine holding an employer or principal liable for the employee's or agent's wrongful acts committed within the scope of the employment or agency.” BLACK’S LAW DICTIONARY 1338 (8th ed. 2004). 2007] MISSOURI HUMAN RIGHTS ACT 949 “the question of whether a supervisor can be liable under the MHRA for the state courts to decide.” 11 1. Lenhardt v. Basic Institute of Technology, Inc. The Eighth Circuit first decided the issue of employee-supervisor liability in Lenhardt v. Basic Institute of Technology, Inc. 12 In that case, the court noted that the Missouri Supreme Court had not yet decided whether individual liability existed under the MHRA. 13 Therefore, the majority had to predict how the Missouri Supreme Court would decide the issue. 14 Reasoning that the Missouri Supreme Court would likely examine comparable statutes in interpreting individual liability under the MHRA – as the Missouri Supreme Court had previously done when interpreting other provisions of the Act 15 – the Eighth Circuit examined analogous federal civil rights statutes: Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (“ADEA”). 16 Title VII defines an “employer” as “a person engaged in an industry affecting commerce who has fifteen or more employees . . . and any agent of such a person.” 17 This language is nearly identical to that of the ADEA’s definition of “employer.” 18 Although the majority in Lenhardt noted that the language of the two statutes was analogous to the MHRA, the court stressed that neither Title VII nor the ADEA were identical to the MHRA. 19 However, the plaintiff contended that the statutes were not analogous, because, unlike Title VII and the ADEA, the MHRA does not require an individual to be an agent of his or her employer for the individual to fall within the statute. 20 The majority rejected the plaintiff’s argument, emphasizing that the 11. Bennett v. Tyson Foods, Inc., No. 1:05CV00052HEA, 2005 WL 1668147, at *3 (E.D. Mo. Jan. 18, 2005). 12. 55 F.3d 377. The court in Lenhardt did not definitively settle the issue, but rather its determination was “merely a prediction” of what the Missouri Supreme Court would do. Shortey v. U.S. Bank, N.A., No. 03-0530-CV-W-SWH, 2003 WL 24225868, at *3 (W.D. Mo. Dec. 5, 2003). 13. Lenhardt, 55 F.3d at 379. Presumably, the plaintiff in Lenhardt brought the suit in federal court because the plaintiff also alleged a violation of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). Id. 14. Id. 15. Midstate Oil Co. v. Mo. Comm’n on Human Rights, 679 S.W.2d 842, 845-46 (Mo. 1984) (en banc). 16. Lenhardt, 55 F.3d at 380-81. 17. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(b) (2000) (emphasis added). 18. 29 U.S.C. § 630(b) (2000) (defining “employer” as “a person engaged in an industry affecting commerce who has twenty or more employees [and] . . . any agent of such a person”) (emphasis added). 19. Lenhardt, 55 F.3d at 380. 20. Id. 131 950 MISSOURI LAW REVIEW [Vol. 72 plaintiff had not directed the court to any authority on point and that the plaintiff’s assertion was not self-evident from the language of the statute. 21 The plaintiff also argued that the decisions of four other circuits, which held that an employee-supervisor was not subject to individual liability under the Title VII, 22 were erroneous, because it is illogical not to hold individuals liable for their discriminatory conduct. 23 Specifically, the Fourth, Fifth, Ninth and Tenth Circuits unanimously interpreted the language, “any agent of such a person,” as creating only respondeat superior liability rather than providing for individual liability against supervisors and co-workers. 24 The plaintiff claimed that these interpretations of Title VII gave individual supervisors and employees a “free pass” to discriminate. 25 The Missouri Supreme Court was not persuaded by the plaintiff’s argument. Instead, the court opined that offending individuals would presumably be subject to some form of discipline from their employer, such as “a ‘free pass’ to the unemployment line.” 26 Ultimately, the court gave deference to the federal interpretations of Title VII and the ADEA in holding that the Missouri Supreme Court would not interpret the definition of “employer” within the MHRA as exposing individuals to liability. 27 2. Cases Since Lenhardt Since the 1995 decision in Lenhardt, Missouri federal courts have been inconsistent in their rulings on individual liability under the MHRA. Those that have sided with Lenhardt and held that the MHRA does not impose individual liability, have done so with reluctance. 28 For instance, in Weger v. City of Ladue, the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri followed the ruling in Lenhardt, despite obvious hesitation. 29 The Eastern District stated that individual employees could “fit comfortably” within the definition of “employer” under the MHRA. 30 However, the court noted 21. Id. 22. Id. (citing Birkbeck v. Marvel Lighting Co., 30 F.3d 507, 510-11 (4th Cir. 1994); Lankford v. City of Hobart, 27 F.3d 477, 480 (10th Cir. 1994); Grant v. Lone Star Co., 21 F.3d 649, 653 (5th Cir. 1994); Miller v. Maxwell’s Int’l Inc., 991 F.2d 583, 587 (9th Cir. 1993)). 23. Id. 24. Id. 25. Id. at 381. 26. Id. 27. Id. 28. See, e.g., Walker v. Lanoga Corp., No. 06-0148-CV-W-FJG, 2006 WL 1594451, at *4 (W.D. Mo. June 9 2006) (quoting Weger v. City of Ladue, No. 4:04CV00683SNL, 2004 WL 3651669, at *5 (E.D. Mo. Dec. 30, 2004)); Weger, 2004 WL 3651669, at *4-5. 29. Weger, 2004 WL 3652669, at *5. 30. Id. at *4. 2007] MISSOURI HUMAN RIGHTS ACT 951 that Lenhardt was still good law, and therefore the Eastern District’s opinion regarding the issue was immaterial. 31 Under the doctrine of stare decisis, the majority was bound to follow the decision in Lenhardt. 32 Similarly, in Klotz v. CorVel Healthcare Corp., the majority followed Lenhardt merely on a stare decisis basis. 33 The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri offered no discussion regarding the substantive accuracy of the decision in Lenhardt. 34 Rather, the Eastern District observed that a district court may not substitute its own view for that of binding circuit law. 35 Accordingly, since neither the Missouri Supreme Court nor the Eighth Circuit Court of appeals had addressed the issue of individual liability under the MHRA, the court in Klotz was bound by the decision in Lenhardt. 36 However, other federal courts have refused to follow Lenhardt, stating that the Eighth Circuit’s interpretation of the MHRA in Lenhardt was erroneous. Those courts which have dismissed Lenhardt have generally taken the view argued by the plaintiff in that case: that the language of the MHRA is broader in scope than that of Title VII. 37 In Shortey v. U.S. Bank, N.A., the court expressed this notion, stressing that the definition of “employer” within the MHRA is more encompassing than the definition within Title VII. 38 Instead, the court found that the language of the MHRA was more comparable to that of Ohio Revised Code Section 4112.01(A)(2) 39 and the Family and Medical Leave Act (“FMLA”). 40 Importantly, the courts which had previ- 31. Id. at *5. 32. Id. 33. Klotz v. CorVel Healthcare Corp., No. 4:05 CV 1034 CAS, 2005 WL 3008515, at *3 (E.D. Mo. Nov. 9, 2005). 34. Id. 35. Id. 36. Id. 37. See, e.g., Wesley v. OCE Bus. Servs., Inc., No. 05-0055CVWSOW, 2005 WL 998624, at *2 (W.D. Mo. Apr. 19, 2005); Hill v. Ford Motor Co., 324 F. Supp. 2d 1028, 1032-34 (E.D. Mo. 2004); Shortey v. U.S. Bank, N.A., No. 03-0530-CV-WSWH, 2003 WL 24225868, at *3 (W.D. Mo. Dec. 5, 2003). 38. Shortey, 2003 WL 24225868, at *3 (citing Darby v. Bratch, 287 F.3d 673, 681 (8th Cir. 2002)). 39. Id. (citing Genaro v. Cent. Transp., Inc., 703 N.E.2d 782, 787 (Ohio 1999)). The Ohio Revised Code provides in relevant part that “‘Employer’ includes the state, any political subdivision of the state, any person employing four or more persons within the state, and any person acting directly or indirectly in the interest of an employer.” OHIO REV. CODE ANN. § 4112.01(A)(2) (LexisNexis 2006). 40. Shortey, 2003 WL 24225868, at *3 (citing Darby, 287 F.3d at 681). The FMLA defines “employer” in relevant part as “any person who acts, directly or indirectly, in the interest of an employer to any of the employees of such employer.” 29 U.S.C. § 2611(4)(A)(ii)(I) (2000). 132 952 MISSOURI LAW REVIEW [Vol. 72 ously interpreted these two statutes found that they provide for individual liability. 41 Noting that Lenhardt was “merely a prediction,” the majority in Shortey dismissed the holding in Lenhardt and gave deference to the federal court holdings interpreting statutes more comparable to the MHRA. 42 Upon examination of those holdings, the court predicted that the Missouri Supreme Court would impose individual liability on employees-supervisors under the MHRA. 43 Similarly, in 2004 the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri rejected Lenhardt, although that same court had previously “followed blindly the holding of Lenhardt.” 44 In Hill v. Ford Motor Co., the Eastern District explained that although the Missouri Supreme Court found Title VII and the MHRA comparable in some respects, the court had also observed significant differences between the two statutes. 45 The majority further stressed that recent federal court decisions had diminished the validity of the holding in Lenhardt by giving negative treatment to the decision.46 The majority adopted the reasoning given in Darby v. Bratch, which held that the definition of “employer” within the FMLA imposes individual liability against employees and supervisors. 47 Since the definition given under the FMLA is closer to the MHRA than is the language of Title VII, the court in Hill stated that the Missouri Supreme Court would probably follow Darby. 48 As a result, the court found a reasonable basis for predicting that the Missouri Supreme Court would impose individual liability under the MHRA, 49 once again adding to the inconsistency of federal court decisions interpreting individual liability under the MHRA. C. Individual Liability under Analogous Employment Discrimination Statutes Since Lenhardt, Missouri federal courts have been divided over the individual liability for supervisors and employees under the MHRA. Accord41. See, e.g., Genaro, 703 N.E.2d at 787; Darby, 287 F.3d at 681. 42. Shortey, 2003 WL 24225868, at *3. 43. Id. 44. Hill v. Ford Motor Co., 324 F. Supp. 2d 1028, 1032 (E.D. Mo. 2004). 45. See id. The court in Hill noted, for example, that the Missouri Supreme Court found that discriminatory “retaliation” is broader in scope under the MHRA than under Title VII. Id. 46. Id. at 1032-33 (citing Fortner v. City of Archie, 70 F. Supp. 2d 1028 (W.D. Mo. 1999); Vacca v. Mallinckrodt Med., Inc., No. 4:96CV-0888(MLM), 1997 WL 33827523 (E.D. Mo. Jan. 15, 1997); Shortey, 2003 WL 24225868; Darby, 287 F.3d 673). 47. Id. at 1033. 48. Id. at 1033-34. 49. Id. at 1034. 2007] MISSOURI HUMAN RIGHTS ACT 953 ingly, federal court decisions do not provide much guidance on the issue. Therefore, an analysis of judicial interpretations of similar federal employment discrimination statutes is helpful. 1. An “Agent” of the Employer Under Title VII, an “employer” is “a person . . . who has fifteen or more employees . . . and any agent of such a person.” 50 The ADEA contains language which is nearly identical to Title VII.51 Courts have almost universally interpreted the language of Title VII and the ADEA as not providing for individual liability against supervisors and co-workers. 52 In addition, those courts which have purportedly imposed individual liability on supervisors and employees have done so “only in their official capacities and not their individual capacities.” 53 Therefore, liability in these cases has been imposed only upon the common employers of the plaintiffs and defendants, not the individual employees. 54 Courts have reasoned that by incorporating the word “agent” into Title VII and the ADEA, Congress intended for the statutes to impose only respondeat superior liability rather than expose individuals to personal liability. 55 To be sure, Congress included the word “agent” specifically to ensure that employers are responsible for the discriminatory acts of their agents, not to impose liability on the agents themselves. 56 The court in Birbeck v. Marvel Lighting Corp. affirmed this reasoning, holding that the term “agent” within 50. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(b) (2000) (emphasis added). 51. 29 U.S.C. § 630(b) (2000) (the ADEA defines an “employer” as “a person . . . who has twenty or more employees . . . [and] (1) any agent of such a person”). See also 42 U.S.C. § 12112(a) (2000) (the ADA defines “employer” in a manner analogous to the ADEA). 52. Powell v. Yellow Book USA, Inc., 445 F.3d 1074, 1079 (8th Cir. 2006) (stating that Title VII imposes liability on employers only); Kimble-Parham v. Minn. Mining & Mfg., No. CIV.00-1242 ADM/AJB, 2002 WL 31229572, at *13 (D. Minn. Oct. 2, 2002) (holding that Title VII prohibits discrimination from employers, not individuals); Yesudian v. Howard Univ., 270 F.3d 969, 972 (D.C. Cir. 2002); EEOC v. AIC Sec. Investigations, Ltd., 55 F.3d 1276, 1281 (7th Cir. 1995); Smith v. St. Bernard’s Reg’l Med. Ctr., 19 F.3d 1254, 1255 (8th Cir. 1994); Birbeck v. Marvel Lighting Corp., 30 F.3d 507, 510 (4th Cir. 1994); Miller v. Maxwell’s Int’l, Inc., 991 F.2d 583, 587 (9th Cir. 1993) (holding that neither Title VII nor the ADEA impose individual liability). 53. Miller, 991 F.2d at 587 (citing Harvey v. Blake, 913 F.2d 226, 227-28 (5th Cir. 1990)). 54. Lenhardt v. Basic Inst. of Tech., 55 F.3d 377, 380 (8th Cir. 1995). 55. Yesudian, 270 F.3d at 972. 56. Gastineau v. Fleet Mortgage Corp., 137 F.3d 490, 494 (7th Cir. 1998). 133 954 MISSOURI LAW REVIEW [Vol. 72 the ADEA’s definition of “employer” does not create individual liability, but simply signals an “unremarkable expression of respondeat superior.”57 Further, courts have suggested that the requirement of “fifteen or more employees” under Title VII, and “twenty or more employees” under the ADEA, evinces that Congress did not intend to impose individual liability under the statutes. 58 Rather, Congress wanted to minimize workplace discrimination while protecting individuals and other small entities from the economic hardship associated with litigating discrimination claims. 59 Courts have advised that it is unlikely that Congress would aim to protect small entities on the one hand, while imposing liability on individual employees on the other. 60 2. “Acting in the Interest” of the Employer Courts have taken a different approach in interpreting statutory language which references individuals “acting in the interest” of the employer, holding that those acting in the interest of the employer are personally liable. The FMLA defines an “employer” in relevant part as “any person who acts, directly or indirectly, in the interest of an employer to any of the employees of such employer.” 61 Generally, courts interpreting the FMLA have held that the language of the statute creates liability which is broader in scope than that of Title VII. 62 Notably, courts which have interpreted the FMLA have generally held that the statute does expose supervisors and employees to individual liability, while Title VII does not. 63 With this interpretive approach, courts have equated the FMLA to the Fair Labor Standards Act (“FLSA”). 64 Importantly, the definition of “employer” in the FLSA is identical to FMLA definition. 65 Since the language of the FLSA has been interpreted to impose individual liability, courts have generally ruled that the FMLA also exposes supervisors and employees to 57. Birbeck, 30 F.3d at 510. The plaintiffs in Birbeck brought action against their employer and vice president, alleging that their layoffs violated the ADEA. Id. at 509. 58. Miller, 991 F.2d at 587. 59. EEOC v. AIC Sec. Investigations, Ltd., 55 F.3d 1276, 1281 (7th Cir. 1995). 60. Id. (citing Miller, 991 F.2d at 587). 61. 29 U.S.C. § 2611(4)(A)(ii)(I) (2000) (emphasis added). 62. See, e.g., Genaro v. Cent. Transp., Inc., 703 N.E.2d 782, 787 (Ohio 1999). 63. See Mitchell v. Chapman, 343 F.3d 811, 827-28 (6th Cir. 2003); Darby v. Bratch, 287 F.3d 673, 680-81 (8th Cir. 2002); Brunelle v. Cytec Plastics, 225 F. Supp. 2d 67, 82 (D. Me. 2002). 64. See Mitchell, 343 F.3d at 827-28; Darby, 287 F.3d at 681; Brunelle, 225 F. Supp. 2d at 82. 65. An employer is “any person acting directly or indirectly in the interest of an employer in relation to an employee.” 29 U.S.C. § 203(d) (2000). 2007] MISSOURI HUMAN RIGHTS ACT 955 liability. 66 The courts’ analyses of the FLSA as imposing individual liability under the FMLA are consistent with federal regulations. 67 The Department of Labor interprets the language of the FMLA as parallel to that of the FLSA, stating that individuals “acting in the interest of an employer” are subject to individual liability under the FMLA. 68 A 1999 decision by the Supreme Court of Ohio also interpreted language similar to the FMLA and the FLSA as imposing individual liability on supervisors and employees. 69 The court in Genaro v. Central Transp., Inc., interpreted an Ohio statute whose definition of “employer” is nearly identical to that of the FMLA. 70 The majority determined that the statute clearly encompassed individual supervisors and managers. 71 The court noted that the purpose of the statute was to “reflect Ohio’s strong public policy against workplace discrimination.” 72 Therefore, imposing individual liability under the statute would limit workplace discrimination, thereby further facilitating the public policy goals of the state of Ohio. 73 The Ohio Supreme Court’s decision reflects the general view that while an “agent” of an employer is not individually liable under employment discrimination statutes, those “acting in the interest” of an employer are individually liable. 74 III. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS The debate over individual liability for employers under the MHRA has gained strength in recent months. The incongruity of Missouri federal court decisions has continued as judges have applied Lenhardt to determine how the Missouri Supreme Court would interpret “employer” under the Act. 75 However, in Cooper v. Albacore Holdings, Inc., a recent decision by the Missouri Court of Appeals, a Missouri state court finally ruled on the issue as a matter of first impression. 76 Accordingly, Missouri federal courts no longer 66. See Mitchell, 343 F.3d at 827-28; Darby, 287 F.3d at 681 (holding that the FMLA is analogous to the FLSA and therefore imposes individual liability); Brunelle, 225 F. Supp. 2d at 82 (comparing the FLSA to the FMLA and holding that both impose individual liability). 67. See 29 C.F.R. § 825.104(d) (2006). 68. Id. 69. Genaro v. Cent. Transp., Inc., 703 N.E.2d 782, 785 (Ohio 1999). 70. See id. (interpreting OHIO REV. CODE ANN. § 4112.01(A)(2) (LexisNexis 2000)). See also OHIO REV. CODE ANN. § 4112.01(A)(2). 71. Genaro, 703 N.E.2d at 785. 72. Id. 73. Id. 74. See supra Part II.C.1-2. 75. See infra Part III.A.; MO. REV. STAT. § 213.010(7) (2000) (defining “employer”). 76. Cooper, 204 S.W.3d 238. 134 956 MISSOURI LAW REVIEW [Vol. 72 have to rely on Lenhardt’s prediction of Missouri’s interpretation of employer under the MHRA. A. Missouri Federal Cases Interpreting “Employer” under the MHRA Missouri federal district courts have recently adhered strictly to Lenhardt as binding precedent in holding that the MHRA does not expose supervisors and employees to individual liability. 77 However, the federal courts of the Eastern District and the Western District of Missouri have been divided over the accuracy of the holding in Lenhardt. The Eastern District has not questioned Lenhardt’s validity in its adoption of the decision, 78 while the Western District has expressed reluctance to follow the holding. 79 For instance, in Smith v. Schnuck Markets, Inc., the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri cited to Lenhardt in ruling that the MHRA does not provide for supervisor liability. 80 The court neither offered its reasoning for following Lenhardt nor criticized the decision. 81 Instead, the majority adopted Lenhardt as binding without question. 82 However, the court did note that Lenhardt has received criticism since the decision was handed down. 83 Such criticism has recently been offered by the United States District Court for the Western District of Missouri. In Baines v. Missouri Gaming Co., the court implied its reluctance to follow Lenhardt by adopting analysis found in Weber v. City of Ladue into its decision: “At the end of the day whether this Court necessarily agrees or disagrees with the holding in Lenhardt is immaterial. This Court under stare decisis must and will follow what is good law, even if under other circumstances this Court could have reached another outcome . . . .” 84 The court’s adoption of this reasoning into its opinion leads to the presumption that the court did not agree with Lenhardt. However, as the court noted, Lenhardt provides the most thorough interpretation of individual liability under the MHRA. 85 Therefore, the Western Dis77. See supra note 2 and accompanying text. 78. Smith v. Schnuck Markets, Inc., No. 4:04CV711 JCH, 2006 WL 1790162, at *5 (E.D. Mo. June 27, 2006). 79. Walker v. Lanoga Corp., No. 06-0148-CV-W-FJG, 2006 WL 1594451, at *4 (W.D. Mo. June 9, 2006); Baines v. Mo. Gaming Co., No. 05-6031-CV-SJ-FJG, 2006 WL 506184, at *2 (W.D. Mo. Feb. 28, 2006). 80. Smith, 2006 WL 1790162, at *5. 81. Id. 82. Id. 83. Id. at *5 n.4. 84. Weger v. City of Ladue, No. 4:04CV683 SNL, 2004 WL 3651669, at *5 (E.D. Mo. Dec. 30, 2004). 85. Baines v. Mo. Gaming Co., No. 05-6031-CV-SJ-FJG, 2006 WL 506184, at *2 (W.D. Mo. Feb. 28, 2006) (quoting Berry v. Combined Ins. Co. of Am., No. 040586-CV-W-FJG (W.D. Mo. Nov. 29, 2004)). 2007] MISSOURI HUMAN RIGHTS ACT 957 trict held that until the Missouri state courts interpret the language of the MHRA, “the better course of action is to follow the Eighth Circuit’s guidance on the issue.” 86 Similarly, in Walker v. Lanoga Corp., the Western District quoted the same above-referenced language from Weber and Baines to express its reluctance to follow Lenhardt. 87 Evidently, although federal district courts have recently upheld Lenhardt, they have not been in agreement over the accuracy of the Eighth Circuit’s decision. B. Cooper v. Albacore Holdings, Inc. 88 Amidst the continued disagreement among the federal courts over the validity of Lenhardt, the Missouri Court of Appeals for the Eastern District became the first Missouri state court to decide the issue of individual liability under the MHRA. 89 In Cooper v. Albacore Holdings, Inc., the plaintiff, Vice President of Human Resources for Albacore Holdings, Inc., brought a twocount claim, in part alleging sexual harassment and retaliation and in violation of the MHRA. 90 Defendants, Albacore Holdings, Inc. and Gordon Quick, the company’s Chief Executive Officer, brought a summary judgment motion as to the plaintiff’s claims, and the lower court granted the motion in favor of the defendants. 91 On appeal, the court of appeals reversed the grant of summary judgment as to the count alleging the defendants’ violation of the MHRA. 92 In a stark departure from the federal precedent, the court held that under the MHRA, defendant Quick may be found individually liable for sexual harassment. 93 In its decision, the court analyzed and dismissed the holding in Lenhardt, which predicted that the Missouri Supreme Court would interpret the MHRA’s definition of “employer” as not providing for individual liability. 94 The court boldly noted that “the Missouri Supreme Court does not blindly follow the ‘predictions’ of the federal courts.” 95 86. Id. 87. Walker v. Lanoga Corp., No. 06-0148-CV-W-FJG, 2006 WL 1594451, at *4 (W.D. Mo. June 9, 2006). 88. Cooper v. Albacore Holdings, Inc., 204 S.W.3d 238 (Mo. Ct. App. 2006). 89. See id. at 243. 90. Id. at 240. According to the plaintiff, defendant Gordon Quick, Albacore Holding, Inc.’s Chief Executive Officer, sexually harassed Respondent during a dinner with the company’s Senior Business Team. Id. at 241. 91. Id. at 240. 92. Id. at 244. 93. Id. 94. Id. at 243; Lenhardt v. Basic Inst. of Tech., 55 F.3d 377, 381 (8th Cir. 1995)). 95. Cooper, 204 S.W.3d at 243 (quoting Hill v. Ford Motor Co., 324 F. Supp. 2d 1028, 1032 (E.D. Mo. 2004)). 135 958 MISSOURI LAW REVIEW [Vol. 72 In rejecting Lenhardt, the majority analyzed decisions of other courts interpreting analogous employment discrimination statutes. 96 For instance, the court examined how courts have interpreted “employer” under Title VII. 97 As previously discussed, the definition of “employer” under Title VII contains the words, “any agent of such a person,” 98 which most federal courts have interpreted to mean that Title VII does not provide for individual liability for supervisors and other employees. 99 However, the court in the present case distinguished the definitions of “employer” under the MHRA and Title VII, stating that the Missouri legislature intended for the definition of “employer” within the MHRA to be “broader in scope than that found in Title VII.” 100 Instead, the court gave deference to decisions in Missouri and other jurisdictions interpreting employment discrimination statutes which are more analogous to section 213.010(7) of the Missouri Revised Statutes. 101 The majority analyzed the court’s decision in Genaro, which interpreted an Ohio statute containing language which is “nearly identical” to that of the definition of “employer” within the MHRA. 102 In addition, the court examined Darby, which interpreted a similar definition of “employer” under the FMLA. 103 Both courts held that the definition of “employer” within the statute did create individual liability for employees. 104 The court in Cooper agreed with the decisions in Genaro and Darby, rejecting the recent federal court holdings and the decision in Lenhardt and holding that the definition of “employer” under the MHRA imposes individual liability for supervisors and employees. 105 Consequently, defendant Quick was subject to individual liability under the MHRA. 106 96. Id. at 243-44. 97. Id. 98. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(b) (2000). See also supra Part II.C.1. 99. Cooper, 204 S.W.3d at 243 (citing Smith v. Amedisys Inc., 298 F.3d 434 (5th Cir. 2002); Yesudian v. Howard Univ., 270 F.3d 969, 972 (D.C. Cir. 2001); Miller v. Maxwell’s Int’l Inc., 991 F.2d 583, 588 (9th Cir. 1993)). 100. Cooper, 204 S.W.3d at 244. 101. See id. at 243-44. 102. Id. (examining Genaro v. Cent. Transp., Inc., 703 N.E.2d 782 (Ohio 1999)); see supra Part II.C.2. 103. Cooper, 204 S.W.3d at 244 (analyzing Darby v. Bratch, 287 F.3d 673 (8th Cir. 2002)); see supra Part II.B.2. 104. Cooper, 204 S.W.3d at 244. See also Genaro, 703 N.E.2d at 787-88; Darby, 287 F.3d at 681. 105. Cooper, 204 S.W.3d at 243-44. 106. Id. at 244. 2007] MISSOURI HUMAN RIGHTS ACT 959 IV. DISCUSSION The argument over individual liability for employment discrimination raises important public policy issues, and the future implications of the Missouri Court of Appeal’s deviation from recent federal court decisions are apparent. A. Arguments Against Individual Liability Those courts that oppose individual liability in connection with employment discrimination have put forth merited arguments. One common argument against individual liability is that even without individual liability, there is a strong incentive to avoid discrimination.107 Specifically, employees know they will be subject to proper discipline for their discriminatory actions, including losing their jobs. 108 In addition, since employing entities are already liable under employment discrimination statutes, they have the incentive to train employees to avoid discriminatory actions. 109 Therefore, the employer “is in the best position to deter agents from discriminating.” 110 Hence, the purpose of discrimination statutes can still be fulfilled without imposing individual liability on supervisors and employees. 111 Further, courts recognize that generally it is the employer that has the financial resources necessary to fully compensate the victim, not the individual discriminator. 112 Employers also have the ability to provide victims of employment discrimination with promotions and reinstatements necessary to negate some of the occupational harm resulting from the discrimination.113 Moreover, courts argue that discrimination statutes are not intended to expose individuals to liability, but rather are intended to protect individuals from liability while at the same time minimizing discrimination. 114 Discrimination statutes generally define “employer” as an entity with a certain 107. EEOC v. AIC Sec. Investigations, Ltd., 55 F.3d 1276, 1282 (7th Cir. 1995). 108. Id.; Lenhardt v. Basic Inst. of Tech., Inc., 55 F.3d 377, 381 (8th Cir. 1995) (stating that an employee may be subject to “a ‘free pass’ to the unemployment line”). 109. AIC Sec. Investigations, 55 F.3d at 1282. 110. Tammi J. Lees, The Individual vs. the Employer: Who Should be Held Liable Under Employment Discrimination Law?, 54 CASE W. RES. L. REV. 861, 878 (2004). 111. See id. 112. Tracy L. Gonos, A Policy Analysis of Individual Liability – The Case for Amending Title VII to Hold Individuals Personally Liable for Their Illegal Discriminatory Actions, 2 N.Y.U. J. LEGIS. & PUB. POL’Y 265, 292 (1999). 113. See Lees, supra note 110, at 886. 114. Miller v. Maxwell’s Int’l Inc., 991 F.2d 583, 587 (9th Cir. 1993). 136 960 MISSOURI LAW REVIEW [Vol. 72 number of employees – usually six or more. 115 Accordingly, some courts have reasoned that it is inconceivable that Congress and state legislatures would protect small entities from liability while at the same time exposing individuals to liability. 116 Finally, courts going against individual liability for employment discrimination consider the plain language of the statute at issue. Importantly, the dissenting opinion in Genaro argued that if the Ohio General Assembly had intended for the discrimination statute at issue in that case to impose individual liability, the General Assembly “could have easily included the word ‘employee.’” 117 The same argument applies to every discrimination statute which fails to include the word “employee” within the statute’s definition of “employer,” including the MHRA. With this in mind, courts have universally maintained that the judiciary’s primary job in interpreting statutes is to determine the legislative intent, giving the wording of the statutes their plain and ordinary meaning. 118 Hence, if the legislature did not include the word “employee” into the definition of “employer,” then courts should deduce that the legislature did not intend to impose individual liability on employees. B. Arguments in Support of Individual Liability Although numerous courts have offered reasonable arguments against individual liability, the explanations in support of individual liability as the sole remedy for employment discrimination are more plausible. Frequently, courts argue that individual liability is the only way to fully satisfy the employment discrimination laws’ deterrence function. 119 By facilitating the antidiscrimination purposes of the laws, the public policy goals of the legislature are fostered. 120 Importantly, although those against individual liability argue that individual employees are deterred through the fear of discipline from their employers, the concern over judicial discipline presumably creates more incentive to avoid discrimination. Judicial intervention is a strong deterrent of discriminatory behavior, because employees fear not only the possibility of 115. See, e.g., 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(b) (2000) (fifteen or more employees); 29 U.S.C. § 630(b) (2000) (twenty or more employees); MO. REV. STAT. § 213.010(7) (2000) (six or more employees). 116. Miller, 991 F.2d at 587. 117. Genaro v. Cent. Transp., Inc., 703 N.E.2d 782, 788 (Ohio 1999) (Moyer, J., dissenting). 118. Cooper v. Albacore Holdings, Inc.,204 S.W.3d 238, 243 (Mo. Ct. App. 2006). 119. See Lees, supra note 110, at 879 (citing Jendusa v. Cancer Treatment Ctrs. of Am., Inc., 868 F. Supp. 1006, 1011 (N.D. Ill. 1994)). 120. Genaro, 703 N.E.2d at 785. 2007] MISSOURI HUMAN RIGHTS ACT 961 employer discipline, but also a potential large monetary penalty imposed by the courts. 121 Courts and commentators also point out that victims of discrimination are more fully vindicated through court imposition of individual liability for supervisors and employees. 122 A monetary judgment is not sufficient for victims of discrimination, who need to know that individuals are held accountable for their discriminatory actions. 123 If employees are not held legally accountable, then they receive an unjust “free pass” to discriminate without fear of legal recourse. The concept of employee immunity for employment discrimination not only inhibits due justice for victims of discrimination, but it is also inconsistent with public policy interests with regard to holding individuals accountable for their wrongful actions. 124 Employees and supervisors who discriminate are more blameworthy than their employing entities, who simply delegated authority to those individuals. 125 Therefore, as one commentator noted, “recognizing employer liability without recognizing agent liability would be anomalous as a legal doctrine.” 126 C. Both Employers and Individuals Should be Liable Accordingly, arguments in favor of both employer and individual liability are the most logical, as they encompass strong reasoning behind both employer liability and individual liability. 127 Those who support this “dual liability” approach argue that it provides the most effective way to both deter employment discrimination and compensate victims, thus accomplishing the two main goals of employment discrimination law. 128 By providing two means of recourse for a victim of employment discrimination, the MHRA would provide a double-deterrence for employees. Individual employees would have the fear of legal liability coupled with the apprehension of employer punishment if the employer was determined to be vicariously liable. 129 In contrast, an interpretation of “employer” under the MHRA which only imposed employer liability may not fully deter employ- 121. Jendusa, 868 F. Supp. at 1012. 122. See Lees, supra note 110, at 880. 123. See Scott B. Goldberg, Comment, Discrimination by Managers and Supervisors: Recognizing Agent Liability Under Title VII, 143 U. PA. L. REV. 571, 584 n.60 (1994). 124. See Lees, supra note 110, at 881 (citing Strzelecki v. Schwarz Paper Co., 824 F. Supp. 821, 829 n.3 (N.D. Ill. 1993)). 125. See Goldberg, supra note 123, at 589. 126. Id. 127. See supra Part IV.A-B. 128. See Lees, supra note 110, at 883. 129. Id. 137 962 MISSOURI LAW REVIEW [Vol. 72 ees. Individual employees would only be subject to employer discipline,130 which is not always an effective means of deterring employment discrimination. As the Northern District of Illinois noted, employers often fail to punish employees for discriminatory conduct, especially if “the individual employees involved are high ranking corporate officials.” 131 The court stated that for these individuals, the fear of employer discipline is not sufficient to deter their discriminatory conduct. 132 Also, some commentators have argued that individuals who are nearing retirement or otherwise plan to terminate their employment do not feel the deterrent effect of vicarious liability for their discrimination. 133 For instance, one who is planning to leave an employer in the near future has no fear of being fired or demoted from a current employment position. In addition, the dual liability method helps to fully compensate victims of employment discrimination. By providing two means of obtaining reparation, the MHRA would ensure that victims received both personal justice and monetary damages. 134 Employers are generally the parties which have the financial resources to fully satisfy victims. 135 In addition, employers can provide victims with the promotions or reinstatements necessary to provide them with justice. 136 However, this is not always the case. Sometimes employers do not have the financial resources to fully compensate victims. 137 In these instances, it is essential to impose individual liability as well as vicarious liability to ensure that victims are sufficiently vindicated. 138 Further, the imposition of individual liability on employees would give victims comfort in knowing that the wrongdoers were receiving direct, judicial punishment for their actions. 139 Therefore, the adoption of only employer liability under the MHRA would not provide for complete personal reparation. By allowing for individual liability as well as employer liability, the MHRA would afford victims an alternative means to recover for employment discrimination. 140 One must keep in mind that under the dual liability approach, victims would not receive a windfall. 141 Rather, the dual liability approach would “provide the [victim] with more than one source of funds but not more than 130. See id. 131. Jendusa v. Cancer Treatment Ctrs. of Am., Inc., 868 F. Supp. 1006, 1012 (N.D. Ill. 1994). 132. Id. 133. See Lees, supra note 110, at 884. 134. See id. at 886. 135. See Gonos, supra note 112, at 292. 136. See supra text accompanying note 116. 137. See Lees, supra note 110, at 886. 138. See id. 139. See Goldberg, supra note 123, at 584 n.60. 140. See id. 141. See id. 2007] MISSOURI HUMAN RIGHTS ACT 963 one complete satisfaction.” 142 Instead of affording victims of employment discrimination with double recovery, the dual liability approach would simply give more effect to employment discrimination law. For the foregoing reasons, it is arguable that the dual liability approach is “the most effective means to deterring and ultimately eliminating employment discrimination.” 143 D. Future Implications of Recent Missouri Decisions Recent Missouri judicial decisions have created an uncertain, yet promising future for employment discrimination law in Missouri. With the recent decision by the Missouri Court of Appeals for the Eastern District, interpreting the definition of “employer” under the MHRA as providing for individual liability, Missouri state and federal courts now have strong precedent in opposition to the ruling in Lenhardt. 144 It is well settled that federal courts interpreting employment discrimination statutes should not “disregard the decisions of intermediate appellate state courts unless [they are] convinced by other persuasive data that the highest court of the state would decide otherwise.” 145 Accordingly, Missouri federal courts that interpret the MHRA in the future will have to follow the decision in Cooper unless they are convinced, not simply persuaded, that the Missouri Supreme Court would rule differently. With such a strict standard, it is unlikely that Missouri federal courts will abandon Cooper and follow Lenhardt in subsequent decisions. 146 Even Missouri federal courts that disagree with the decision in Cooper will probably still follow Cooper as binding precedent, as the federal courts have recently done with Lenhardt. 147 142. See Lees, supra note 110, at 886 (quoting Dan B. Dobbs, THE LAW OF TORTS § 385 (2000)). 143. See id. at 883. 144. Cooper v. Albacore Holdings, Inc., 204 S.W.3d 238, 243-44 (Mo. Ct. App. 2006) (refusing to follow Lenhardt v. Basic Institute of Technology). Importantly, the Missouri Court of Appeals for the Eastern District recently affirmed its holding in Cooper, thus giving more weight to the decision. Brady v. Curators of Univ. of Mo., 213 S.W.3d 101, 113 (Mo. Ct. App. 2006). 145. Genaro v. Cent. Transp., Inc., 703 N.E.2d 782, 786 (Ohio 1999) (emphasis added) (quoting Garraway v. Diversified Material Handling, Inc., 975 F. Supp. 1026, 1030 (N.D. Ohio 1997)); Comm’r of Internal Revenue v. Estate of Bosch, 387 U.S. 456, 465 (1967). 146. The significance of Cooper is already evident within the Missouri federal courts. In granting a recent motion to remand, a United States District Court for the Western District of Missouri cited Cooper, stating that the answer to the question of whether Missouri courts would conclude that the MHRA allows claims for individual liability is “easy, given that some Missouri courts have concluded that such a cause of action is viable.” Barnes v. Dolgencorp, Inc., No. 06-0632-CV-W-ODS, 2006 WL 2664443, at *1-2 (W.D. Mo. Sept. 14, 2006). 147. See supra note 2 and accompanying text. 138 964 MISSOURI LAW REVIEW [Vol. 72 Moreover, Missouri state and federal judicial affirmations of Cooper will more effectively accomplish the goals of Missouri’s employment discrimination law. By imposing both employer and individual liability, the MHRA will provide a more effective means of deterrence, thus helping to minimize employment discrimination. 148 In addition, future victims of employment discrimination will have a better opportunity to receive full monetary compensation and personal vindication. 149 The decision in Cooper will eliminate the “free pass” for both employers and employees, and provide victims of discrimination with fair and due justice. V. CONCLUSION The imposition of individual liability under the MHRA is consistent with the overarching goals of Missouri’s employment discrimination laws: to deter discriminatory conduct in the workplace and to fully compensate victims of employment discrimination. Since the implementation of the MHRA, Missouri federal courts have debated whether the MHRA’s definition of “employer” provides for individual liability for employees and supervisors. Although recent Missouri federal judicial decisions have held that the MHRA does not impose individual liability, the Missouri Court of Appeals for the Eastern District rejected that view and held in a case of first impression that individual employees are subject to liability under the MHRA. The Eastern District’s decision is fair and consistent with public policy reasoning. To be sure, the decision will finally allow victims of employment discrimination to attain full reparation. In addition, the Eastern District’s holding will help eliminate employment discrimination altogether by deterring individuals from engaging in discriminatory conduct. Although the recent decision by the Eastern District has helped to further the goals of employment discrimination law, one cannot be comfortable with Missouri’s new interpretation of “employer” until the Missouri Supreme Court has ultimately ruled on the issue. RICHARD D. WORTH 148. See supra Part IV.C. 149. See supra Part IV.C.