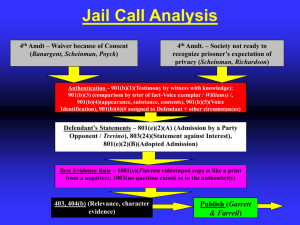

Crawford Confrontation Clause and Hearsay Laboratory Drug Reports I.

advertisement