Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference

9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7

Customer Value Creation In Healthcare - Network Perspective

Justyna Matysiewicz* and Slawomir Smyczek**1

The dynamic development of medical services sector in European Union creates the

demand for analysis and evaluation of the medical organization operating in this sector. This

issue deserves attention both from the theoretical and practical the point of view. In the

healthcare sector, different healthcare providers, such as home care, primary care,

pharmacies and hospital clinics but also a financial institution, collaborate in order to

increase values for patients, such as better health state, more complex services, high quality

of services, and increased feeling of safety. By creating a value, flexible healthcare network

providers and additional actors create the value through collaboration. The issues addressed

in the article focuses on marketing activities of healthcare services networks in the context of

customer value creation. The aim of the study is identification and description the process of

value for customer creation in healthcare networks.

JEL Codes: M31, D12, and D14

1. Introduction

Well-developed economies are characterized by the interaction of two important trends: an

increased role of services in the economy, and an increased role of knowledge in the technological

and social innovation development process (emergence of the information society and knowledgebased economy and innovation). Nowadays, knowledge has become a central element of

production of goods and services, and learning itself constitutes an important process in the

economic development. Peter F. Drucker characterized this new type of economy by emphasizing

the role of leading groups composed of skilled workers or trained practitioners who are able to use

the knowledge for production purposes (Drucker, 1999). M. Castells has also pointed out that the

key element of knowledge economy is a network organization, and network, as a form of

organization of production, distribution and management, is an analogy to contemporary economic

development (Castells 2011). Increased access to resources, distribution of responsibility and risk

reduction, flexibility and adaptation to the changing global environment, mobility of knowledge and

skills are the main advantages of network structures.

Essential to any business networks is the underlying system through which it produces value. This

value–system construct is based on the notion that each product/service requires a set of value

creating activities performed by a number of actors forming a value-creating system (Möller and

Rajala, 2007). A value-creating system is a set of activities that create value for consumers

(Parolini, 1999). Various resources are used in carrying out these activities, linked by various kinds

of flows. Value-creating systems contain several economic actors who may be involved in more

than one value-creating system. Within the value net model, economic activity is thought of not in

terms of a set of economic actors who internally perform a set of activities, but as a set of activities

that create value for final customers (Parolini, 1999).

1

*Justyna Matysiewicz Ph.D, University of Economics in Katowice, Department of Market Policy and Marketing

Management, 1 Maja 50, 40–287, Katowice, Poland, justyna.matysiewicz@ue.katowice.pl

**Prof. Slawomir Smyczek Ph.D, University of Economics in Katowice, Department of Consumption Research, 1 Maja

50, 40–287, Katowice, Poland, slawomir.smyczek@ue.katowice.pl

Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference

9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7

The issues addressed in the article focuses on marketing activities of healthcare services networks

in the context of customer value creation. The aim of the study is identification and description the

process of value for customer creation in healthcare networks.

Research was finance by National Center of Science (NCN) based on decision number DEC2013/11/B/HS4/01470.

2. Literature Review

The category of value frequently appears in social sciences, including economics. Despite this,

scientists find the category difficult to define and often avoid precise definition thereof, which

results in ambiguities hindering the process of researching the consumption value for customers.

Due to subjective and situational character of the value, analysis should be focus on the concept of

customer in consumption sphere.

The term customer value was first introduced into the marketing theory in 1954 by P. Drucker on

the occasion of presenting the concept of marketing corporate management (Drucker, 1954).

Towards the end of 1960s, this category appeared in the theory of consumer behavior and referred

to the concept of utility (benefit) and satisfaction, known from the theory of consumer choice

(Howard and Sheth, 1969, Kotler and Levy, 1969). Later, the use of its original sense was dropped,

and the concept of “value” appeared only in studies into consumer behavior where it was

considered as declared and respected values, or as values preferred by buyers (customer values).

The notion of value for money recurred in its broader use in economic sciences at the end of 1980s

thanks to M. Porter’s research into corporate competitive advantage and his development of a

chain model of added-value (Porter, 1985).

M. Porter’s views on customer value (called by him value for buyer) were based on his abundant

scientific work on consumer, containing results of research into consumer satisfaction carried out in

1980. Thanks to M. Porter’s study, the term of customer value has been widely adopted in the

contemporary concepts, including: Total Quality Management, Business Process Reengineering,

Supply Chain Management, Value Based Management and Customer Relationship Management

(Szymura-Tyc, 2003).

Also in 1990s the category reappeared as a subject of scientific interest in the theory of marketing

supported by the theory of consumer choice, consumer behavior and consumer psychology. The

term customer value was used alongside such notions as utility, benefits, needs and satisfaction.

Reasons for development of research into customer value were diverse. First, the concept of utility,

a basic category of consumer choice theory, did not put enough emphasis on costs borne by the

consumer in the process of buying and using some definite goods. In the consumer choice theory,

utility was regarded as tantamount to consumer satisfaction with benefits from using a product

(Kamerschen et al., 1991). Research into consumer satisfaction proved, however, that satisfaction

experienced by the consumer depends not only on benefits that the consumer gains from buying

and using a product (utility), but from relevant costs that he /she must bear - Theory of Exchange

Fairness (Jachnis and Terelak, 1998). This necessitated development of a category which could

both reconcile gained benefits and costs to be borne by the consumer. Secondly, research into

consumer satisfaction showed that satisfaction appeared only when results from buying and using

a product exceeded customer’s expectations of a product at the very moment of product selection Model of Expected Discrepancy (Furtak, 2003). Considering product utility and satisfaction as

equal did not allow for identification of this relation. Thus, it was necessary to find a category that

Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference

9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7

could enable researchers to study the relationship between consumer satisfaction, his/her

expectations with respect to products and results of purchase and consumption thereof, with full

consideration of both benefits to be gained and costs to be borne by the buyer.

All the research into the consumer and marketing has resulted in the development of the notion of

customer value. The definition of the category was based not only on classical marketing theories,

but also on modern theories of behavior and consumer psychology. The notion development was

also supported by achievements of service marketing and conclusions drawn from a contemporary

concept of relationship marketing. Researchers have also referred to M. Porter’s chain model of

added-value, which combines value for the customer with added-value for the buyer and the

company. Many attempts have been made to define the concept of value for the customer, as well

as to determine attributes of the category and ways of measuring thereof.

V. Zeithaml defines customer value by exploiting the concept of product utility. Here, the value is

an aggregate consumer evaluation of product utility based upon consumer’s perception of what is

gained against what is given (Zeithaml, 1988). V. Zeithaml emphasizes that customer value is a

subjective and differently perceived category, whereas price constitutes a significant criterion, but

its influence on consumers may vary. The author also notices that clear and legible use instruction

manual or an assembly manual may be an important factor in consumer perception of a product

value. Moreover, this value may be looked upon differently, depending on circumstances of its

consumption.

K. Monroe, in turn, claims that the value perceived by buyers comes from the relation between the

quality or benefits that the buyer recognizes in a product and perceived sacrifices (loss) he/she

makes by paying a given price. K. Monroe claims that perceived benefits are composed of physical

attributes of a product, attributes connected with accompanying services and technical support

during product utility, as well as of price and other quality indexes. Perceived costs, in turn,

comprise costs borne by the buyer during the purchase, such as: product price, costs of purchase

related to e.g. transfer of title deeds, costs of assembly, costs of exploitation, maintenance (repairs)

costs, failure risk or product malfunction risk costs. By assuming that most buyers operate within

financial constraints (in the theory of consumer choice – financial constraints, K. Monroe

maintained that buyers were more susceptible to borne costs (sacrifices, losses) than to potential

benefits), he proposed customer value to be measured by the ratio of benefits to costs, and not by

the difference existing between them. It is valuable in adding that the proposed concept did not

elicit big response in marketing literature. However, majority of the authors are inclined to define

the value as a difference (excess) between the perceived benefits and costs. This seems justified

inasmuch as the concept of the perceived costs signifies the cost which is subjectively perceived

by the customer. Nonetheless, it should be borne in mind that different customers have diverse

reactions to particular cost components (price, effort, time, etc.). With certain financial constraints

related to their income, buyers may be more or less susceptible to price and other components of

perceived costs (Szymura-Tyc, 2005).

Considerate contribution to the definition of customer value was made by A. Ravald and Ch.

Gronroos, researchers connected with the concept of relationship marketing, who extended the

definition of value proposed by K. Monroe. They pointed out to the fact that, apart from the value

of a product itself (company’s offer), there exists a distinct value, being a result of the relationship

between transaction parties. In their opinion, there are many situations where, despite consumer

dissatisfaction with one of transactions, some prior positive experience which contributed to

development of the relationship between the customer and the company encourages him/her to

seek compromise. With regard to this, A. Ravald and Ch. Gronroos proposed to take into account

Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference

9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7

costs and benefits ensuing from the relationship between the buyer and the seller, alongside

unpredicted “accidental” costs and benefits connected with a given transaction, as they jointly

influence the value perceived by the customer. Thus, they referred to concepts elaborated by

consumer psychology, known as transaction and accumulated satisfaction, and to the Affective

Model of consumer satisfaction. According to the authors, the so-called aggregate unpredicted

accidental value is represented by the ratio of accidental benefits and benefits resulting from the

relationship to accidental costs and costs resulting from the relationship (Ravald and Gronroos,

1996).

The concepts of transaction satisfaction, accumulated satisfaction and the so-called attributive

satisfaction, being notions of the consumer psychology, were used at great length by R. Woodruff

in his approach to customer value, which he defined as a composition of preferences experienced

and evaluated by the customer. These preferences refer to attributes of a product itself, of its

functioning, and finally of product consumption effects, thanks to which the customer can (cannot)

achieve his/her goals and intentions in the process of product consumption (Woodruff, 1997). This

definition represents a hierarchical system of customer value, which implies a need for its

assessment at the level of attributes of a product and product consumption as well as customer

goals and intentions. Moreover, this system reveals not only the process of value development, but

also best represents the relation between customer value and satisfaction. Thus, it can be treated

as a basis for measuring satisfaction derived from assessment of value delivered to the customer

(Woodruff, 1997). In his approach to the value definition, R. Woodruff demonstrates a dynamic

character of customer value, which means that it may change with time. The need for a dynamic

approach to the customer value is also emphasized by A. Parasuraman, who points out to the fact

that customers who make a purchase for the first time tend to concentrate on product attributes,

whereas those who do it repeatedly pay more attention to effects of product consumption and

possibilities of achieving certain goals relating to definite goods (one product) or a service

(Parasuraman, 1997).

Customer value has been also a subject of Ph. Kotler’s analyses who defined it as a difference

between the total customer value and the total customer costs. The total value is composed of a

bundle of benefits anticipated by the customer, whereas the total cost is made up of a bundle of

costs expected by the customer in connection with the evaluation, purchase and consumption of a

product or service (Kotler, 1997). According to Ph. Kotler, the total customer value comprises an

anticipated value of a product, service, personnel and corporate image. The total cost, on the other

hand, is composed of such costs as money, time, energy and psychical cost expected by the

customer (Smyczek, 2012). In his definition, Ph. Kotler (1997) underlines the fact that customer

value is not delivered to the customer (as Ph. Kotler initially declared), but is expected by him/her.

Alongside the above-mentioned definitions of customer value, marketing literature presents several

others which, in great detail, refer to some selected issues connected with the concept of customer

value. All the definitions reflect the multifaceted character of studies conducted by scientists and

marketing theorists occupied with research into the category. Although not all of them are

considered successful, the overview of the definitions helps in understanding problems

encountered by researchers. To provide some examples, B. Gale defines customer value as

quality perceived on the market in relation to price of a given product (Gale, 1994). The value on

industrial markets is, in turn, a perceived equivalent, expressed in monetary units, of a bundle of

economic, technical, social or service benefits gained by the customer’s company for a price paid

for a product with respect to offers and prices of other deliverers (Anderson et al., 1993). According

to S. Slater and J. Narver (2000), customer value appears when product-related benefits outweigh

costs of the life cycle of a product being consumed by the customer. For the institutional customer,

Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference

9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7

the benefits materialize along with the growth of a unit profit or with an increase in the number of

sold product units. The costs of life cycle of a product being consumed by the customer comprise

costs related to product finding, to product operational costs, product disposal costs and to its price.

Customer value is perceived as an emotional relation between the customer and the producer as a

result of consumer consumption of a product or a service which, in his/her opinion, provided

him/her with added value (Butz and Goodstein, 1996).

Bearing in mind the above-presented definitions and contemporary achievements in the theory of

consumer behaviors, consumer psychology and marketing theory, it can be concluded that

customer value appears in the process of consumption of a purchased product. This value is

developed through consumer’s subjective estimation of costs and benefits after product purchase

and consumption. These costs and benefits are the only significant element in the assessment of

the value obtained by the customer, and customer value itself represent predominance of benefits

over costs perceived by the customer. Based on this, one can venture a statement that customer

value is an excess of subjectively perceived benefits over subjectively perceived costs related to

purchase and consumption of a given product.

Benefits gained by customers are connected with needs they want to satisfy through some product

purchase and product consumption. Individual customers seek benefits which can meet their

consumption needs. Costs, in turn, have generally a financial dimension connected with exchange

of goods and money between the company (seller) and its customer (buyer). Beside the financial

costs, there are costs which refer to consumer time loss, inconvenience, customer extra efforts,

negative emotions, etc.

In the discussion of customer value, distinction should be made between the value which is

expected and the value which is obtained by the customer. The value expected by the customer

can be referred to as an excess of subjectively perceived and expected benefits and costs relating

to product purchase and consumption. In light of this definition, such a value constitutes basis for

customer market choices, and is tightly related to the concept of utility in the theory of consumer

choice. As for value gained by the customer, i.e. customer value, it can be defined as an excess of

subjectively perceived customer benefits over subjectively perceived customer costs, being the

result of product purchase and consumption (Glowik and Smyczek, 2015). Such a definition of a

customer value corresponds with the notion of customer advantage in the theory of consumer

choice and with added-value introduced to the management literature by M. Porter.

With respect to the above-discussed issues, the following attributes of customer value can be

distinguished:

subjectivity – customer value is not dependent solely on a service itself, but on customer’s

individual needs to be satisfied by a company, and on customer’s individual capability of covering

costs related to product purchase and product use,

situational character - benefits and costs related to purchase and use of a product are always

conditional on a situation in which product is bought; depending on a situation, the same customer

may have different perception of benefits to be won and costs to be borne,

perceived value - this means that the assessment of a customer value comprises only benefits

and costs which are perceived (recognized) by the customer, and not benefits which were really

gained or costs which were borne by him/her; the very process of benefit and cost perception is

connected not only with cognitive processes, but also with the emotional ones (Glowik and

Smyczek, 2015) .

Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference

9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7

All the attributes of customer value do not allow direct measuring of the category. Although

customer satisfaction can be used as a basic benchmark for customer value estimation, yet, it

should be remembered that satisfaction itself is not exclusively dependent on the value gained, but

also the value expected by the customer. Even more so, satisfaction appears only when effects of

product purchase and use go beyond consumer expectations of these results.

Another important attribute of customer value concerns its dynamic character, which means that

the value changes over time, embracing the whole process of service purchase and product use. In

its endeavor to provide a customer with some value, a companies ought to focus on the whole life

cycle of a product, including all costs and relevant benefits. Thus, customer value represents a

complex set of benefits and costs perceived by the customer in the process of buying and using

products. It is impossible to enumerate all benefits and costs, being components of value for the

customer, because their number and variety correspond with the number of customer’s needs,

expectations and constraints. These needs, expectations and constraints are subject to alterations,

since satisfaction of some needs opens the door to other, more superior ones. Needs change or

diversify, and new ones arise, thus necessitating development of new products which can meet

customers’ changing needs and expectations, and which can adapt to customers’ varying

constraints. Being aware of the fact that benefits and costs are the only determinants of a customer

value perceived by the customer, companies tend to arrange miscellaneous activities which are

designed to teach customers to appreciate attributes of their products. In practical terms, a

companies can create and model customers’ needs and expectations with respect to offered

product, and ultimately, may affect assessment of the final value gained by customers.

Marketing is about managing profitable customer relationships. The twofold goal of marketing is to

attract new customers by promising superior value and to keep and grow current customers by

delivering satisfaction (Armstrong & Kotler, 2007). Creating value for customers has been

recognized as a key concept in marketing (e.g. Sheth & Uslay 2007; AMA definition of marketing,

Chartered Institute of

Creation and delivery of the value for the customer, being the prerequisite for a competitive edge,

is especially significant with respect to system-based health care services. An increasingly

common systemic character of products and services results from the customer’s perception of

their value, namely their existence in a definite and developed system of products and/or services

and in networks of their users. Possible benefits gained from the purchase and from the use of

systemic products depend on existence and operation of other related products or services

(Parolini, 1999; Matysiewicz, 2014).

Healthcare Value Networks

According to Kähkönen (2010) a value net is a dynamic, flexible network in which the actors create

value through collaboration (e.g. Allee, 2003; Bovet and Martha, 2000a,b; Jarillo, 1998; Parolini,

1999). The value net model was developed to facilitate the analysis, description and study of valuecreating systems, and takes activities rather than companies as the key elements of strategic

analysis (Parolini, 1999). Companies are regarded as complex nodes in complex interdependent

value nets, where success comes through collaboration and creating a business environment in

which each actor can be successful (Allee, 2003). Any network where the participants are engaged

in these kinds of exchange relations can be seen as a value network, whether the value network

has been acknowledged by its participants.

Nowadays it can be noticed the growing interest of value net concept in healthcare. Progressing

integration of the medical sector actors is indicated by the emergence of healthcare value nets. To

the major advantages connected with the value network strategy of HCOs are (Matysiewicz 2007):

Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference

9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7

-

possibilities of widening the existing offers with new services, and at the same time

broadening the range of service offers,

-

possibilities of diminishing of doctors’ mistakes, because of the bigger number of

operative specialists,

-

ensuring the safety flowing from the safety of customers directed to the organization from

other co-operating doctors,

-

motivation for investment in new technologies what allows rising the quality of services,

-

bigger resources for marketing activity flowing from the synergy effect.

co-

Healthcare organizations develop value nets to increase the chances of them being able to survival

and grow. Healthcare value nets concern service-oriented collaboration between at least two

independent entities, which build economic and business relationship (Powell et al., 1996).

Networks in the field of medical services it is a joint effort of companies already operating in the

market (although on a smaller scale) in order to search for new market opportunities in the field of

exploring new markets, identify new customers, create new, often more integrated market offers

what can respond to costomers' expectations better. The process of integration of medical services

can be divided into three main components, the areas of networking (Fleury, Mercier 2002):

-

Functional Area / Administration, responsible for the supervision, management, marketing,

information flow, resource allocation, and effectiveness.

-

Clinical area, responsible for improving service process. It means that service have to be

synchronized according to treating periods (eg. before and after hospitalization), and during the

period of treatment (eg.: psychological support, home care). This component forms the basis for

the creation of the process of service delivery.

-

The area of the medical system. It is directly responsible for the quality of medical personnel

and treatment process involves the active participation of doctors in the network.

The integration process affects all of these components. It means restructuring medical practices,

service offerings, organizational structures adoption.

Knowledge Transfer in Value Networks

One of the main role of value networks is related to the knowledge transfer. A network allows a

better sharing of newest findings in order to reuse in during new knowledge creation. The

knowledge transfers allows to create and deliver much more advanced value for the consumer.

The critical knowledge type that is distributed throughout the network is tacit knowledge. This

phrase was first coined by Polanyi (1966) and used to describe a form of knowledge that cannot be

explicated and that is embodied through practice. At the heart of this concept is the notion of tacit

‘knowing’: here, the outcome of action is the focal, or proximal, point and the doing (achieving the

outcome) is characterised as a distal process. The critical skills and knowledge of employees and

their social practices may become localised within a project team, network or a more informal

community-of-practice (Wenger, 2000; Yanow, 1999) within the organisation. It is essential for the

success of the organisation that this knowledge is integrated between the different pockets and

shared throughout. Connections need to be made between the potentially disparate parts of the

organisation if the knowledge is to be developed (Swart, Kinnie, 2003).

The basic approach to knowledge transfer is to consider knowledge transfer as knowledge sharing

among people (Dyer and Nobeoka, 2000). Knowledge sharing implies the giving and taking of

Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference

9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7

information framed within a context by participants involved. Knowladge transfers requires the

willingness of the group or individual to work with others and share knowledge to their mutual

benefit. Without sharing, it is almost impossible for knowledge to be transferred to other person.

This shows that knowledge transfer will not occur in an organization unless its employees and work

groups display a high level of co-operative behaviuor (Goh, 2002).

Some researchers view knowledge transfer as a process through which knowledge moves

between a source and a recipient and where knowledge is applied and used (Szulanski, 1996,

2000; Szulanski, Cappetta and Jensen, 2004). Within an organization, knowledge can be

transferred among individuals, between different levels in the organizational hierarchy and between

different units and departments. Szulanski (1996, 2000) defines knowledge transfer as “dyadic

exchanges of knowledge between a source and a recipient in which the identity of the recipient

matters” (Babinska, Matysiewicz 2014). The level of knowledge transfer is defined by the level of

knowledge integrated within an individual and the level of satisfaction with transferred knowledge

expressed by the recipient. Almeida, Song and Grant (2002) view knowledge transfer as a process

of creation, transfer, application and subsequent development through combination of the

transferred knowledge with the recipient’s existing knowledge. Others focus on the resulting

changes to the recipient by seeing knowledge transfer as the process through which one unit is

affected by the experience of another (Argote and Ingram, 2000). Similarly, Davenport and Prusak

(2000) suggested that the knowledge transfer process involves two actions: transmission of

knowledge to potential recipient; and absorption of the knowledge by that recipient that could

eventually lead to changes in behavior or the development of new knowledge. Model introduced by

Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) explains knowledge transfer based on knowledge conversion model.

Modes of knowledge transfer can take four forms, i.e. Socialization, Externalization Combination

and Internalization (SECI). According to Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995), socialization refers to an

organizational process through which tacit knowledge held by some individuals is transferred in

tacit form to others with whom they interact. Externalization refers to the transformation of some

tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge, via theories, concepts, models, analogies, metaphors and

so on. Combination refers to the conversion of codified knowledge into new forms of codified

knowledge. Internalization is a process of conversion of explicit knowledge into a tacit form. Each

mode of conversion constitutes one means of knowledge transfer and creation (Cohendet et al,

1999).

3. Reserch Methodology

The research was conducted in 2014 by means of exploratory, case research method. The

research design was qualitative and exploratory in nature. As stated by McCracken (1988)

qualitative research does not survey the terrain, it mines it, and therefore can be seen as more

intensive than extensive in its objectives. Similarly Eisenhardt (1989) focuses on utilising a casebased approach for theory-driven research.

The basis for selecting the case studies was the approach applied by J. Collins and J.I Porras

(1994). They studied 'truly exceptional companies' and compared them with another set of very

good companies. In every case, they put their iconic company up against a comparator, at some

point, held equal stature in the same industry. They studied how the two diverged from that point

on and then looked for patterns across all the winners. Both semi structured interviews and

analysis of secondary data were used for data collection. The companies selected for the research

are healthcare medical unitis, representing the network organisation. Case A is represented by

Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference

9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7

Leader, a multinational company which has been actively involved in development of a network of

medical entities in EU since 1994. Currently, it is run 100 centers and cooperates with a network of

1500 independent medical entities throughout EU. The company provides healthcare services to

one million patients. Case B represents a comparative company called Specialist which has been

operating on the Polish market for three years. The company owns 3 medical centers in Poland,

yet, its pace of growth is high and exceeds that of the competition. Interviewees were senior

managers within their firms, possessing international experience in international markets. The main

objective of the research was to determine the role, the scope and significance of value networks in

the process of developing and delivering the value for the consumer of health care services. The

research included two health care networks operating in in Poland.

4. Results of Research And Discussion

The two cases did not provide the same amount of information under each research question and

themes but the phenomenon under investigation is well represented in every case and in this

manner the stories that unfold across the two cases aggregately provide a comprehensive

understanding.

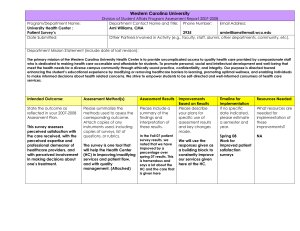

Leader can be assigned to the current network. It is a network of individuals with a very secure and

stable bases of operation. Relationship between network elements suggest creating a network of

vertical and horizontal connection. The main objective of the operation is to increase its access to

complementary resources, increase operational efficiency, growth opportunities, and access to a

wider group of customers. Its important feature is the hierarchical coordination of distribution

network. The network is integrated, formal and highly structured and open for new entities. Leaders

in addition to the distribution network (horizontal relationships), responsible for delivering value,

builds a network of its own units (initiating, taking over) responsible for the enrichment and

comprehensive service offerings (value creation). Relationships between them are vertical and

based on the value added. Value creation system itself is well illustrated in the network, and the

network itself has a relatively stable resources and processes forming a specific customer value.

The units responsible for value creation are an integral part of the Leader. Relationships between

units and the Leader are highly structured and formal.

In the case of Leader network it can be noticed that the system of knowledge management

comprises all entities/units. The system of knowledge management in such a multinational network

is composed of definite standards and procedures, e.g. with respect to marketing, financial matters

or human resources. In this context, huge formalization and strict procedures in all aspects of

corporate operation appear as a disadvantage, yet, they are designed to create more transparent

and easy-to-manage structure all over the world. The network represented by Leader has a good

system of security of knowledge transfer including the so-called emergency system. Another

important element positively affecting operation of the company is transfer information between

network units as well as between the external environment.

Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference

9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7

Figure 1: The value creation in Leader healthcare network

Benefits of Network

Medicover

Medical center

Medcover (1)

Medical

packages

(systemic

product)

Medicover

insurance

MC Medcover (n)

Medicopharma

Syneva

Med

ivov

er

Gru

p in

Pola

nd

MC independent

MC independent

(2)

Mass

individualisation

of the product

Value

for

custome

r

MC independent

InviMed

Medicover Poland

Medicover Hospital

Medicover Poland

MC Medcover (2)

Patient

Brand

Service

standards

availability 48h

mobile services

service i on-line

independent

N

Telephone

services

Care Expert

Relationship Marketing

Creating the Value

Communicating the value

Delivery the value

Leader attaches great importance to communication processes, and therefore uses a lot of internal

communication tools such as trainings, conferences, regular information meetings as well as the

Intranet and teleconferencing. It is noteworthy that, due to its dominant position on the market,

Leader enjoys greater freedom in gaining information from network partners than the partners

themselves. Network units are obliged to maintain regular contacts and to report its performance to

Leader. However, it is a common practice for Leader to keep certain information and not to

disclose it to other network partners, which reveal a unilateral character of this communication.

Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference

9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7

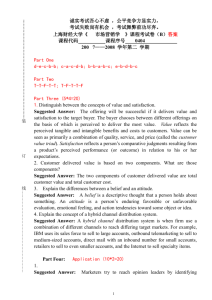

Figure 2: The value creation in Specialist healthcare network

Benefits of Network

Medical

Acupuncture

Psycho

prevention

Individual

medical

systemic

product

Medical center

Katowice (1)

Medical center

Warszawa (2)

Brand

Imane

Service

standards

PATIENT

Anti-aging

medicine

Medical Centre Preveneo

Micro nutrition

Value for customer

for customer

Medical balance

Medical center

Bielsko-Biała(3)

Functional

Rehabilitation

Relationship Marketing

Creating the Value

Communicating the value

Delivery the value

The second researched entity on the medical market is Specialist. It is an emerging network. It is a

network of professional individuals with a relatively unstable structure of the operation. From the

goal point of view they adopt a similar structure to the dominant design networks. However,

because of intangibility of the services the basics of its operation are different. The project

approach is focused around new, innovative, highly customized methods for creating and offering

services or customer contact. The advantage of the network is built based on cooperation within

the network, in a situation where a single company can not just get such a dominant position. An

important feature of this network it is building the structures around the customer value process.

Specialist network consists of branches mainly cooperating on a contractual agreements

(organisationally and financially independent units) within certain areas of activity. The network

builds horizontal relations and it is open to new elements. There are no rigidly defined acceptance

criteria. The decision is made after analysis of each particular case. It is important The

relationships between units are diagonal, partly competing and partly complementary. In a formal

sense, there is a center / core of the network. The units responsible for customer value creation are

well known. As mentioned earlier the links between them are less structured and open. The

network models differ significantly in the area of network organization, type of network connections,

and the process of creating, communicating and delivering the customer value.

Specialist, as a company operating on the medical market does not possess a clearly definite

system of knowledge management within the network. The company’s idea is to provide and share

knowledge in every possible way, whereas the security system of knowledge transfer is not of such

great concern as in the case of Leader. Specialist is willing to share its knowledge through trainings

or publications. Another important element positively affecting operation of the studied companies

is information transfer between network units as well as between the external environment. In the

case of Specialist, internal domestic communication is dominated by direct contacts, telephone

conversations and e-mails. In addition, Specialist arranges trainings for its personnel, yet, in a

Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference

9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7

limited scope. On the international level the communication within the network takes place through

mailing, tele-conferencing and traditional correspondence (Matysiewicz et al., 2014).

Compared healthcare networks differ significantly in terms of: network organization, the process of

creating, communicating and delivering value, formation/levels of customer value and participation

of the patient in the process of value creation. Features presented in Table 1 became the basis for

comparison.

Table 1: Qualitative comparative analysis of healthcare networks’ in the context of the creation of

value for the customer

Features

1. It creates strong network links

2. Open to new network elements

3. Selection of the candidates for networks

4. It owns the brand

5. Coordinates the activities of the network

6. A large number of network elements

7. It is a large company

8. Long operating on the market

9. It has a defined value for the customer

10.

Network participants create value for the

customer

11. Participants in the network have an impact on

value creation for the customer

12. The patient is a participant in the value creation

process

13. Builds long-term relationships with clients

14. It offers systemic products

15. The flow of information and knowledge in the

network is free

16. Communicates the value

17. It uses an integrated marketing information system

18. It uses new technologies

19. It has an extensive distribution and sales network

20 It has a marketing department

21. Conducts marketing research

In total

Leader

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

Specialist

X*

√**

√

√

√

X

X

X

√

√

X

√

X

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

19

√

√

X

X

X

√

13

* not having the specific characteristics ** having the specific characteristics

In terms of network management features 1- 3 are referring to acquiring process of new members

of the network (elements), number 5 refers to supervision of the network. Figures 6 and 7 describe

network size, while features 9-14 are associated with the process of creating value for the

customer. Features 16,17 describe the communication process and 18,19 are responsible for the

process of delivering value. Features 20,21 and 4 refer to the concept of market operations.

The results of the qualitative comparative analysis allows for comparison of the processes of

building, communicating and delivering value for the patients in both healthcare networks. In terms

of build and control the entire network (features 1-8) Leader meets all the criteria, which means

strict control and the highly structured structure. It creates and controls the concept of customer

value in an autocratic manner with minimal other network elements involvement. Specialist is much

more flexible in terms of active inclusion of members of the network in the process of creating

value, also enables patients as part of this process. Despite the different time functioning on the

Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference

9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7

market and size, both networks are open to new elements and expand the structure of value

delivery. Leader utilizes brand and reputation as a tool for growth market penetration together with

the concept of mass customization of their products. Specialist is geared towards greater

individualization of its offer, more direct, almost a family relationship with the patient and

recommendations are used

5. Conclusion

The main conclusions of the research suggest that all companies under the research fall in the

group category of the so-called present networks. The operation of these networks is based on

solid foundations, and is oriented on building relations between network components and,

simultaneously, on developing both vertical and horizontal networks. The main objective of the

network operation is to increase access to complementary resources and to gain a wider customer

portfolio, as well as to boost effectiveness and get new market opportunities. These networks are

also characterized by hierarchic coordination of distribution within the network; they are formal and

significantly structured, but also open to new elements. Value-creation system is well defined in the

surveyed companies. However, the Leaders’ system unlike Specialist one is highly structured and

standardized. It is assumed no consumer involvement in the process of value creation.

6. References

1.

Armstrong, G. & Kotler, P. 2007. Marketing: An Introduction. 8 th ed. New Jersey: Pearson

Prentice Hall

2.

Allee, V. 2008, "Value network analysis and value conversion of tangible and intangible

assets",Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 5-24.

3.

Almeida, P., Song, J., & Grant, R. M. 2002. Are Firms Superior to Alliances and Markets?

An Empirical Test of Cross-Border Knowledge Building. Organization Science, 13(2), 147-161.

4.

Anderson, J. Jain, D. and Chintagunta, P. 1993. Customer Value Assessment in Business

Markets: A State-of Practice Study, Journal of Business Marketing, Vol. 1, No 1

5.

Argote, L.; Ingram, P. 2000. "Knowledge transfer: A Basis for Competitive Advantage in

Firms". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 82(1): 150-169.

6.

Babinska D., Matysiewicz J. 2014. International expansion and transferring knowledge - the

case of Polish diagnostic companies, Papaerpresented at EMAC Conference, Katowice, Poland

7.

Bovet, D. and Martha, J. 2000a. Value Nets: Breaking The Supply Chain To Unlock Hidden

Profits, John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY

8.

Bovet, D. and Martha, J. 2000b. Value nets: reinventing the rusty supply chain for

competitive advantage", Strategy & Leadership, Vol. 28 No. 4, pp. 21-6.

9.

Butz, H. and Goodstein, L. 1996. Measuring Customer Value: Gaining the Strategic

Advantage, Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 24, No 3

10.

Castells M.: 2011. Społeczeństwo sieci, PWN, Warsaw. Poland

11.

Cohendet, P., Kern, F., Mehmanpazir, B. and Munier, F. 1999. Knowledge coordination,

competence creation and integrated networks in globalize firms. Cambridge Journal of Economics.

23

12.

Collins J., J.M. Porrtas: 2008 Wizjonerskie organizacje. Skuteczne praktyki najlepszych z

najlepszych. Wydawnictow MT Biznes Ltd., Warsaw, p.35

13.

Davenport, T.H. and Prusak, L. 2000. Working Knowledge - How Organizations Manage

what They Know, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA

14.

Drucker, P. 1954. The Practice of Management, Harper, New York

Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference

9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7

15.

Drucker P.F. 1999. Społeczeństwo pokapitalistyczne, PWN, Warsaw. Poland

16.

Dyer, J.H. and Nobeoka, K. 2000. Creating and managing a high-performance knowledgesharing network: the Toyota case', Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 21, pp. 345-67

17.

Eisenhardt, K.M. 1989. Building theories from case study research, Academy of

Management Review , Vol. 14, 532-550.

18.

Furtak, R. 2003. Marketing partnerski na rynku usług, PWE, Warszawa

19.

Fleury, M., Mercier, C. 2002. Integrated local networks as a model for organizing mental

health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, Vol. 30, No. 1. September, p. 59

20.

Gale, B. 1994. Managing Customer Value, The Free Press, New York

21.

Glowik, M., Smyczek S. (ed.) 2015. Healthcare. Market dynamics, strategies and concepts

in Europe. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin

22.

Goh, S.C. 2002. Managing effective knowledge transfer: an integrative framework and some

practice implication, Journal of knowledge management, Vol. 6, No.1,

23.

Howard, J. and Sheth, N. 1969. The Theory of Buyer Behaviour, John Wiley and Sons, New

York

24.

Jachnis, A and Terelak, J. 1998. Psychologia konsumenta i reklamy, Branta, Bydgoszcz

25.

Kamerschen, D., McKenzie, R. and Nardinelli, C. 1991. Ekonomia, Fundacja Gospodarcza

NSZZ „Solidarność”, Gdańsk

26.

Kähkönen A. 2010. Value net - a new business model for the food industry? British Food

Journal Vol. 114 No. 5, 2012 pp. 681-701

27.

Kotler, Ph. 1997. Marketing Management. Analysis, Planning, Implementation and Control,

Prentice-Hall International Inc., New Jersey 1997

28.

Matysiewicz J. 2014. Marketing organizacji sieciowych usług profesjonalnych w procesie

tworzenia wartości dla klienta, Publishing House UE Katowice, Katowice. Poland

29.

Matysiewicz, J., Smyczek, S., & Babińska, D., 2014 Sektor usług profesjonalnych

usieciowienie, umiędzynarodowienie i dyfuzja wiedzy, Placet, Warszawa

30.

Matysiewicz J.,2007 Developing health care networks to deal with marketing problems in:

Marketing and Business Strategies for Central and Eastern Europe pod red. R. Springera i P.

Chadraby, Wyd. Institute of International Business Vienna University of Economics and Business

Administration, Austria

31.

McCracken, G. 1988. The Long Interview, USA, Sage Publications.

32.

Möller K., A. Rajala 2007. Rise of strategic nets - New modes of value creation, Industrial

Marketing Management, Vol. 36,

33.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. 1995. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese

Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation. New York, Oxford University

34.

Parasuraman, A. 1997. Reflections on Gaining Competitive Advantage through Customer

Value, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 25, No 2

35.

Parolini, C. 1999. The Value Net: A Tool For Competitive Strategy, John Wiley & Sons,

36.

Polanyi, M. 1966. The Tacit Dimension, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

37.

Powell, Walter W., Kenneth W. Koput, and Laurel Smith-Doerr. 1996. "Interorganizational

Collaboration and the Locus of Innovation: Networks of Learning in Biotechnology." Administrative

Science Quarterly 41: 116-45.

38.

Porter, M. 1985. Competitive Advantage. Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance,

The Free Press, New York

39.

Ravald, A. and Gronroos, Ch. 1996. The Value Concept and Relationship Marketing,

European Journal of Marketing Vol. 30, No 2

40.

Sheth, J.N., Newman, B.I. and Gross, B.L. 1991. Consumption Values and Market Choice.

Theory and Applications, Journal of Business Research

Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference

9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7

41.

Slater, S. and Narver, J. 2000. Intelligence Generation and superior Customer Value,

Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 28, No 1

42.

Smyczek, S. 2012. Nowe trendy w zachowaniach konsumentów na rynkach finansowych.

Placet, Warszawa

43.

Szymura-Tyc, M. 2003. Budowa przewagi konkurencyjnej przedsiębiorstw, Ekonomika i

Organizacja Przedsiębiorstw No 1

44.

Szymura-Tyc, M. 2005. Marketing we współczesnych procesach tworzenia wartości dla

klienta i przedsiębiorstwa, AE, Katowice

45.

Swart J., Kinnie N. 2003. Sharing knowledge in knowledge-intensive firms Human Resource

Management Journal, Vol 13 No 2,

46.

Szulanski, G. 1996. Exploring internal stickiness: impediments to the transfer of best

practice within the firm. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 17, special issue

47.

Szulanski, G. 2000. The process of knowledge transfer: a diachronic analysis of stickiness.

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 82

48.

Szulanski, G., Cappetta, R., & Jensen, R. J. 2004. When and How Trustworthiness Matters:

Knowledge Transfer and the Moderating Effect of Casual Ambiguity. Organization Science, 15(5)

49.

Wenger, E. 2000. Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization, 7: 2,

50.

Woodruff, R. 1997. Customer Value: The Next Source for competitive Advantage, Journal of

the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 25, No 2

51.

Yanow, D. 1999. 'The languages of "organizational learning": a palimpsest of terms'.

Proceedings from the Third International

52.

Zeithaml, V. 1988. Consumer Perception of Price, Quality and Value: a Means-End Model

and Synthesis of Evidence, Journal of Marketing vol. 52, No 3