Proceedings of 4th European Business Research Conference

advertisement

Proceedings of 4th European Business Research Conference

9 - 10 April 2015, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-72-6

Market Structure and Political Differentiation of

Newspapers in the Framework of Two-sided Markets

Hend Ghazzai*

We consider two editors competing in both the newspapers' market

and the advertising market. We assume that readers may be

positively or negatively affected by advertising and advertisers are

positively affected by the audience of the newspaper. We

characterize the equilibria of a game where editors must choose their

political content, their prices and their advertising rates. We show

how two-sided interactions affect both the market structure and the

political content of newspapers.

Keywords: Two-Sided Markets, Advertising, Newspapers' Competition, Political

Differentiation

JEL Code: L11

I.

Introduction and Literature Review

Commercial media such as newspapers, magazines, TV channels operate in two

markets. They sell their product to readers or viewers and they sell advertising space

to advertisers. Readers are affected by the amount of advertising in such media and

advertisers take into consideration the audience of the media when making

advertising decisions. These demand linkages are referred to in the literature as twosided network effects1.

In this paper, we study the press industry. Taking into consideration the dependence

of editors on advertisers and their need to satisfy politically differentiated readers, the

objective is to examine the consequences of such effects on the market structure

and on the political content of newspapers. Will a competitive market structure

prevail at equilibrium or will two-sided network externalities confirm the tendency of

concentration observed in media markets? The nature of content delivered by the

newspapers is also a crucial issue. Will editors offer a differentiated content tailored

to different types of readers or a standardized and moderated content corresponding

to a neutral reader? While the first question about market structure has been well

studied in previous works either in the media industry framework or in the general

framework of two-sided markets, the second question received little attention. To our

knowledge, the political content of newspapers was not studied in the framework of a

two-sided market2.

While advertisers are clearly positively affected by the audience of the media, the

attitudes of readers or viewers toward advertising is not obvious. This attitude is

mainly affected by the type of media and is also country specific. It is generally

*

Dr.Hend Ghazzai, Department of Finance and economics, College of Business and Economics,

Qatar University. P.O. Box 2713 Doha, Qatar. E-mail: hend.ghazzai@qu.edu.qa. Tel: +974 44 03 50

86. Fax: +974 44 03 5081

1

See (Rochet and Tirole , 2003) and (Armstrong, 2006) for the literature review about two-sided

markets.

2

(Gabszewicz et al, 2002) study the political differentiation of newspapers when readers are not

affected by advertising.

Proceedings of 4th European Business Research Conference

9 - 10 April 2015, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-72-6

accepted that TV viewers are negatively affected by advertising3. However, readers

of newspapers may be positively or negatively affected by advertising. In the US,

many papers either theoretical or empirical support the positive effect of advertising

on readers ((Blair and Romano, 1993), (Rosse, 1980), (Bogart, 1989), (Ferguson,

1983)...). In Europe, consumers' reactions to advertising are more mitigated and

readers can be either positively or negatively affected by advertising. Advertising

may be considered in the latter case as polluting the main objective of a newspaper

which is to deliver valuable information (See (Musnick,1999) and (Sonnac, 2000). In

this paper, like in (Ferrando et al, 2008), we consider the general case of a

continuum of readers where a proportion are ad-avoiders and the rest are ad-lovers.

In the literature on two-sided markets applied to the media industry, authors assume

the existence of either positive or negative network externalities for the audience.

The negative externalities where mainly studied in the broadcasting market where

the good into consideration is a public good4. When consumers value advertising

positively, the main result is that there is a tendency to market concentration in the

media industry5. To our knowledge only (Ferrando et al, 2008) consider two types of

readers ad-avoiders and ad-lovers.

Unlike (Ferrando et al, 2008), we do not impose exogenously fixed locations for the

newspapers. In addition to the determination of the market structure that prevails at

equilibrium, we also determine the type of political content that will be offered by

editors. In fact, we analyze the decisions in terms of newspaper prices, advertising

rates and political locations of two competing editors in both the newspapers and

advertising markets. We assume that readers and advertisers first form expectations

about the advertising space in each newspaper and about the readerships

respectively. Editors then decide where to locate on the political spectrum and set

newspaper prices and advertising rates simultaneously. Finally, advertisers and

readers make their purchase decisions. We characterize the fulfilled expectations

equilibria of this game and show how the equilibria are affected by the intensity of

the audience feelings about advertising and by the type of the audience i.e. whether

the audience is constituted of a majority of ad-lovers or a majority of ad-avoiders.

We prove that different market structures may prevail at equilibrium: a symmetric

duopoly, an asymmetric duopoly or a monopoly. When the market structure is a

duopoly, newspapers choose maximum differentiation and locate at the extremities

of the political spectrum. Therefore, competition leads to divergent ideologies of the

newspapers. Editors cater to consumers' beliefs and deliver an extremist content

targeting extremist readers. When a monopoly emerges at equilibrium, the

newspaper offers a neutral content and locates at the middle of the political spectrum

delivering an unbiased content. It seems that the lack of competition resulting from

strong feelings toward advertising is compensated by the type of political content

offered by the surviving editor.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2, introduces the model. We

present the results in Section 3 . We conclude in section 5.

3

See (Gal-Or, 2003), (Anderson and Coate, 2005), (Gabszewicz et al, 2004) for theoretical model and

(Brown and Rotchild, 1993), (Danaher, 1995) and (Dukes, 2004) for empirical models.

4

See (Choi, 2006), (Cunningham and Alexander, 2004), (Masson et al, 1990) and (Anderson and

Coate, 2005).

5

See (Armstrong, 2005), (Rochet and Tirole, 2003), (Hackner and Nyberg, 2008)).

Proceedings of 4th European Business Research Conference

9 - 10 April 2015, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-72-6

II.

The Model

We consider two editors selling one newspaper each to a population of readers and

selling advertising space in their newspaper to a population of firms. Thus, each

editor has two revenue sources: an editorial revenue generated by the sales of the

newspaper itself and an advertising revenue generated by the sales of the

advertising space. Consumers in each market will make their consumption decisions

based on the expected demands in the other market. In fact, advertisers' demands

depend on their expectations about newspapers' sales and readers' purchase

decisions are affected by the amount of advertising they expect to find in the

newspaper.

We denote by and

the amount of advertising in each newspaper expected by

readers and we denote by

and

the readership of each newspaper expected by

advertisers.

The Newspaper Market

We consider a population of readers characterized by their political opinion t and

distributed on the political spectrum [0, 1], Editor 1 is located at distance

from

point 0 and Editor 2 is located at distance

from the point 1. At each point t of

the political spectrum [0,1], there corresponds a continuum of readers [0,1] divided in

two sub-groups: a proportion of readers are ad-avoiders and a proportion 1- are

ad-lovers.

Ad-avoiders lose utility when the advertising space in the newspaper increases. Adlovers gain utility when the advertising space in the newspaper increases. The

parameter β measures the intensity of ad-aversion or ad-attraction of readers and is

assumed to be positive.

The utility loss of an ad-avoider reader located at distance t on the political spectrum

and buying newspaper 1 is given by:

The utility loss of an ad-avoider reader located at distance t on the political spectrum

and buying newspaper 2 is given by:

The utility loss of an ad-lover reader located at distance t on the political spectrum

and buying newspaper 1 is given by:

The utility loss of an ad-lover reader located at distance t on the political spectrum

and buying newspaper 2 is given by:

An ad-avoider who is indifferent between buying newspaper 1 or newspaper 2 is

characterized by for which the equality 6

holds, i.e.

6

It is assumed here that

examined later.

or

Thus,

The case where

will be

Proceedings of 4th European Business Research Conference

9 - 10 April 2015, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-72-6

An ad-lover who is indifferent between buying newspaper 1 or newspaper 2 is

characterized by for which the equality

(

)

holds, i.e.

We notice that

and thus

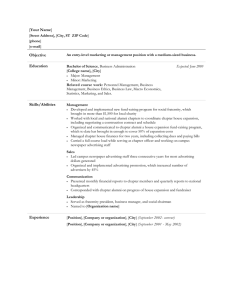

Figure 1 illustrates newspaper’s demands in both cases

assuming that each editor has a positive market share.

and

Figure 1: Newspapers’ Demands

𝑥𝑒

𝑥𝑒

𝑥𝑒

1

𝑥𝑒

1

𝛾

𝛾

0

𝑡𝛼

𝑡𝜆

1

0

𝑡𝜆

𝑡𝛼

1

Buy Newspaper 1

Buy Newspaper 2

We denote by

. The demand for newspapers are as follows:

The demand function of newspaper 1 is

if

if

if

The demand function of newspaper 2 is

if

if

if

The difference (

) and the proportion of ad-avoiders play an important role

in determining the demand of each newspaper. At equal prices and for symmetric

locations, if readers expect newspaper i to attract more advertisers than newspaper j

(

) and if there is a majority of ad-lovers

the readership of

newspaper i will be more important than the readership of newspaper j. On the

contrary, if there is a majority of ad-avoiders, newspaper j will have more readers

than newspaper i.

Proceedings of 4th European Business Research Conference

9 - 10 April 2015, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-72-6

We now study the case

follows:

If

and

, the demand functions are given as

if

and

(

if

and

)

if

In case both editors choose to locate at the center and at equal prices, the

newspaper which is expected to offer more advertising attracts the ad-lovers and the

newspaper which is expected to offer less advertising attracts the ad-avoiders.

Finally, when both newspapers choose to locate at the center of the political

spectrum and if

then the newspaper with the lowest price attracts all the

demand and if prices are equal then

.

The Advertising Market

The advertisers are characterized by their willingness to advertise in a newspaper.

They are uniformly distributed on the unit interval [0, 1]. Each advertiser

buys

exactly one ad in only one of the two newspapers. The utility of an advertiser

depends on the expected readership of each newspaper

.The utility of buying an

ad from newspaper i increases proportionately to the expected readership. More

precisely, the utility of buying an ad in newspaper i at the unit rate

is given by

This is a vertical differentiation model a la Mussa and Rosen for the advertisers. The

advertiser who is indifferent between advertising in newspaper 1 or 2 is given by:

̂

̂

̂

In the previous equality, it is assumed that

. The case where advertisers

expect the same readership for both newspapers is examined below:

If

then

and

.

If

then

and

.

If

If

and

then

o If

o If

then

and

.

and

The Fulfilled Expectations Equilibrium

Editors will choose their locations (political orientation), prices and advertising rates

according to the following sequencing:

Proceedings of 4th European Business Research Conference

9 - 10 April 2015, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-72-6

1. Readers form expectations about the advertising volumes in the newspapers

and advertisers form expectations about the readership of each newspaper.

2. Editors choose their location on the political spectrum.

3. Editors choose the price of their newspapers and the advertising rates

simultaneously.

4. Readers and advertisers make their purchase decisions.

We consider a fulfilled expectations equilibrium represented by a couple of strategies

(

)

and a vector of

expected demands

such that

I.

II.

Each editor chooses its location, newspaper price and advertising rate as a

best reply to the location and prices of the competitor, given readers' and

advertisers' expectations.

Expectations are fulfilled, i.e if

then

and if

then

. If

then

and if

then

.

If an equilibrium exists, it is a Bertrand equilibrium given the expectations of readers

and advertisers. As at the Bertrand equilibrium, the expectations may not be fulfilled,

by condition 2, we restrict the equilibria to those where expectations are fulfilled.

III.

Results

We now determine the equilibria of the game presented in Section II by backward

induction. We characterize the price equilibrium, the location choice of the editors

and we examine fulfilled expectations equilibria.

1. The Price Equilibrium

Given the readership expectations

and

, the advertising expectations

and

and the newspapers locations and , we determine the newspapers' prices and

the advertising rates of each editor. Editors have two sources of revenue: an editorial

revenue and an advertising revenue. Editor i’ s profit is given by:

Lemma 1 characterizes the prices and demands in the newspaper market and

Lemma 2 characterizes the prices and demands in the advertising market. All prices

satisfy condition 1 of our equilibrium.7

Lemma 1 The pair of prices satisfying condition (1) of the Bertrand equilibrium and

the corresponding newspapers demands are as follows:

If

)

)

)

)

)

7

If

)

All proofs are provided in the Appendix.

then

then

Proceedings of 4th European Business Research Conference

9 - 10 April 2015, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-72-6

)

If

)

then

)

For symmetric locations and if there is a majority of ad-lovers, the newspaper which

is expected to attract the more advertisers sets a higher price for its newspaper and

attracts more readers. The opposite occurs when there is a majority of ad-avoiders.

If readers expect one editor to attract much more advertisers than the other only one

editor survives at equilibrium.

The price equilibrium given by Lemma 1 implicitly supposes that

or

.

When

and

, we easily prove from newspapers' demands that a

price equilibrium does not exist as best response functions do not exist for both

editors. When

and

the price equilibrium is when both newspapers

set prices equal to 0.

Lemma 2 The pair of prices

satisfying condition (1) of our equilibrium and the

corresponding advertising demands are as follows:

if

then

(

)

and

if

then

̅

̅

and

if

then

and

2. Location Choice

In this section, we determine editors' locations i.e. the political image of the

newspaper. We focus on two cases that depend on the advertising expectations and

on the intensity of ad-aversion or ad-attraction .

Readers may expect one editor to attract much more advertisers than the

other. This situation happens when (

)

. In this case should be

sufficiently high so that the previous inequality is satisfied.

Proceedings of 4th European Business Research Conference

9 - 10 April 2015, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-72-6

Readers may expect editors to offer similar advertising spaces. This situation

happens when

(

)

. In this case should not be very high8.

We have the following results:

Lemma 3 The best location choices for firms are:

if

if

if

then

*

and

then

*

and

then

+ Only newspaper 1 is active.

and

+ Only newspaper 2 is active.

Both newspapers are active.

The concentration of the market depends on advertising expectations. If advertising

expectations favor one newspaper then only one newspaper is active. Depending on

the sign of

i.e. depending on whether there is a majority of ad-lovers

or a majority of ad-avoiders, the active editor is the editor that attracts the more

advertisers if there is a majority of ad-lovers and the editor that attracts the less

advertisers if there is a majority of ad-avoiders. As (

) is greater than 1, there

is market concentration only when readers are very sensitive to advertising. More

interestingly, the active editor locates at the middle of the political spectrum. The

editor's ideology is then at the center offering an unbiased content to a neutral

reader. The loss in terms of competition is thus compensated by the unbiased

content offered by the editor.

If readers expect editors to offer similar advertising spaces and if they are not very

affected by advertising, both firms are active at the location stage of the game and

editors will offer a completely differentiated content as they will locate at the

extremities of the political spectrum. However, the equilibrium will not be symmetric

in terms of prices and demands if readers do not expect exactly the same advertising

space in each newspaper. The market is thus competitive and editors target

extremist readers.

When

we have proved in the previous section that the only possible price

equilibrium is when

In this case, the editors set a null price for their

newspapers and do not generate any profit from the readers. The locations' choice

(

) is then dominated by the choice (

).

3. The Fulfilled Expectations Equilibria

We now characterize the fulfilled expectations equilibria.

Proposition For any value of

there exists a fulfilled expectations symmetric

equilibrium where newspapers offer a completely differentiated content, with equal

prices and markets shares. This equilibrium is unique when

When

8

, there also exists two other types of equilibria:

We only have partial results for the case

are not easy to fully characterize.

(

)

as the optimal newspapers' locations

Proceedings of 4th European Business Research Conference

9 - 10 April 2015, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-72-6

If (

)

only newspaper i is active. The active newspaper is located

at the middle of the political spectrum.

If

(

)

, both newspapers are active and are located at the

extremities of the political spectrum. Newspaper i has a higher demand and

attracts more advertisers.

When there is majority of ad-avoiders (

) only a unique equilibrium exists and

this equilibrium is symmetric. This equilibrium is such that

. At

equilibrium, newspapers demands are equal to . Newspapers prices are equal to 1.

Advertising demands are equal to and advertising rates are equal to 0. Newspapers

offer a completely differentiated content (

). This equilibrium also exists

when

. When the expectations are symmetric then the equilibrium is symmetric.

The editors do not generate any profit from the advertising market and their only

revenue source is from the newspaper market.

In case of significant ad-attraction, the editor which is expected to offer more

advertising is more attractive to readers. The more readers the editor attracts, the

more advertisers will wish to advertise in its newspaper and so on until the

competitor exits the market. A sort of "circulation spiral" occurs. The concentration in

the newspaper industry seems to be generated by a high ad-attraction and the

dependence of editors on advertising.

If ad-attraction is not very significant, the newspaper which is expected to offer more

advertising is the leader in both the advertising and the newspaper markets. The

leading editor sets higher prices in both markets.

IV.

Conclusion

We have studied in this paper, the strategies of two editors competing in both the

newspapers market and the advertising market and we have shown how two sided

interactions affect the market structure and the type of political content offered by

editors.

The paper can be extended in many ways. We can examine the case were

advertisers in addition to the audience also care about the political opinion delivered

by newspapers and prefer not to publish in very extremist ones. This may eliminate

some of the equilibria where editors locate at the extremities of the political

spectrum. We may also consider the case of targeted advertising and how it affects

the equilibria. Finally, we can distinguish between two types of content delivered by

newspapers: the political content and the non-political one and examine how

advertising affects the spaces allocated to each type of content in the newspaper.

References

Anderson, S.P. and Coate, S. 2005, Market Provision of Broadcasting: A Welfare

Analysis, The Review of Economic Studies, 72(4), p.947-972.

Armstrong, M. 2006, Competition in Two-Sided Markets, The Rand Journal of

Economics, Vol.37, No.3, pp.668-691.

Proceedings of 4th European Business Research Conference

9 - 10 April 2015, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-72-6

Blair, R.D. and Romano, R.E. 1993, Pricing Decisions of the Newspaper Monopolist,

Southern Economic Journal, 59, p.721-732.

Bogart, L. 1989, Press and Public: Who Reads What, Where and Why in American

Newspapers, 2nd ed, Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Brown, T.J. and Rothschild, M.L. 1993, Reassessing The Impact of Television

Advertising Clutter, Journal of Consumer Research, 20(1), p.138-146.

Choi, J.P. 2006, Broadcast Competition and Advertising with Free Entry:

Subscription VS Free-To-Air, Information Economics and Policy, 18, p.181-196.

Cunningham, B.M. and Alexander, P.J. 2004, A Theory of Broadcast Media

Concentration and Commercial Advertising. Journal of Public Economic

Theory, 6, p.557-575.

Danaher, P.J. 1995, What Happens to Television Ratings During Commercial

Breaks?, Journal of Advertising Research, 35(1), p.37-47.

Dukes, A. 2004, The Advertising Market in a Product Oligopoly, Journal of Industrial

Economics, 52 (3), p.327-348.

Ferguson, J.M. 1983, Daily Newspapers Advertising Rates, Local Media CrossOwnership, Newspaper Chain, and Media Competition, Journal of Law and

Economics, 26, p.635-654.

Ferrando, J., Gabszewicz J.J., Laussel D. and Sonnac N. 2008, Intermarket network

externalities and competition: An application to the media industry, International

Journal of Economic Theory, 4(3), p.357-379.

Gabszewicz, J.J, Garella P.G. and Sonnac N. 2007, Newspapers' Market shares and

the Theory of the Circulation Spiral, Information Economics and Policy, 19,

p.405-413.

Gabszewicz, J.J, Laussel D. and Sonnac N. 2002, Press Advertising and The

Political Differentiation of Newspapers, Journal of Public Economic Theory,

4(3), p.317-334.

Gabszewicz, J.J, Laussel D. and Sonnac N. 2004, Programming and Advertising

Competition in The Broadcasting Industry, Journal of Economics and

Management Strategy, 13(4), p.657-669.

Gal-Or, E. and Dukes A. 2003, Minimum Differentiation in Commercial Media

Markets, Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 12(3), p.291-325.

Godes, D., Ofek E. and Sarvary M. 2009, Content VS Advertising: The Impact of

Competition on Media Firm Strategy, Marketing Science, 28(1), p.20-35.

Hackner, J. and Nyberg S. 2008, Advertising and Media Market Concentration,

Journal of Media Economics, 21, p.79-96.

Masson, R., Mudambi R. and Reynolds R. 1990, Oligopoly in Advertiser-Supported

Media, Quarterly review of Economics and Business, 30(2), 3-16.

Musnick, I. 1999, Le Coeur De Cible Ne Porte Pas la Publicite Dans Son Cœur, CB

News, 585, 11-17 Octobre, p.8-10.

Rochet, J.C. and Tirole J. 2003, Platform Competition in Two-Sided Markets, Journal

of the European Economic association, 1(4), p.990-1029.

Rosse, J.N. 1980, The Decline of Direct Newspapers Competition, Journal of

Competition, 30, p. 65-71.

Sonnac, N. 2000, Readers attitudes Towards Press Advertising: Are They Ad-lovers

or Ad-averse?, Journal of Media Economics, 13(4), 249-259.

Proceedings of 4th European Business Research Conference

9 - 10 April 2015, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-72-6

Appendix

Proof of Lemma 1. When both newspapers have positive demands. The derivatives

of the editors' profits with respect to prices are given by:

Setting both derivatives equal to 0 leads to the following first order conditions:

The solution to the first order conditions are given by:

with corresponding demands given by

As both demand must be positive the condition

)

must hold.

To completely characterize the price equilibrium, we need to determine the reaction

functions of both firms and then to examine their intersections. The reply functions of

Newspapers 1 and 2 are given by:

{

{

By

distinguishing

3

cases:

)

)

and

)

, we determine the intersection points of the reply functions as given in

Lemma 1. ■

Proof of Lemma 2. Obvious. It is the price equilibrium of a vertically differentiated

market when the market is covered. ■

Proceedings of 4th European Business Research Conference

9 - 10 April 2015, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-72-6

Proof of Lemma 3. Let us first examine the case

check that the inequality

is never satisfied whatever are

and

)>1. We can easily

)

. Thus, only Editor 1 can be

active at equilibrium and the best location for Editor 1 is

choose any location

while Editor 2 will

.

The optimal locations when

the previous case.

)<-1are found using the same argument as in

Let us now examine the case

)

We will determine the best

location choice of Editor 1 as a function of the location choice of Editor 2 and the

best location choice of Editor 2 as a function of the location choice of Editor 1.

The profit of newspaper 1 is given by:

The derivative of

with respect to

is

if and only if

As

then has

two roots

√

√

The variation table of is then given by

+

As

-

+

, to find the location that maximizes editor 1’s profit, we need to discuss

the position of

and

with respect to 0 and .

Proceedings of 4th European Business Research Conference

9 - 10 April 2015, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-72-6

We easily check that as

)

. Now let us compare

We have that

then

and

if and only if

.

Let us study the sign of

. The quadratic expression has

√

two roots

√

and

We easily check that

Thus:

We also easily check that

and

If

The root

then for every

.

9

if and only if

.

,

and

thus

If

then if

,

and if

,

.

The optimal strategies of Editor 1 are then:

If

If

)

then

)

then

√

o if

then

o if √

then

Now we compare

and

(

or .

)when

)

and

√

(

First,

)

(

)

is negative and therefore

(

is decreasing with respect to

)

. Then,

is negative then positive and therefore

decreases and then increases with respect to .

By

9

√

(

)

because

) and

)<

.

(

√

(

) first

).

Proceedings of 4th European Business Research Conference

9 - 10 April 2015, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-72-6

We find that

√

(

(

)

) approaches

when

approaches and

, there is only one

o if

o if

√

(

). As

(

)

√

such that

then

then

Similarly, the best strategy of Editor 2 is the following:

If

If -

)

such that

o if

o if

then

)

√

then there exists only one

then

then

The equilibrium at the location stage of the game is given by

reply functions intersect at this point for

).■

as the best

Proof of Proposition 1. We first examine the symmetric expectations case where

and

. Then, we have that

)

and thus

,

,

,

and

Using the fulfilled expectations

equilibria condition, we have that

.

Next, we prove that only this symmetric equilibrium exists when

Without loss of

generality let us assume that there exist an asymmetric equilibrium such that

. We examine the two cases

) < -1 or .

If

) < -1, editor 2 is active. Thus

and

, a contradiction with the fulfilled expectations equilibria.

The same reasoning holds when demands but

, which means that

and thus

, both editors have positive

Hence, a contradiction.

Two other equilibria may exist when

i.e. when there is a majority of ad-lovers.

The fulfilled expectations condition is satisfied in both cases:

) >1 and

)< .■