Document 13310628

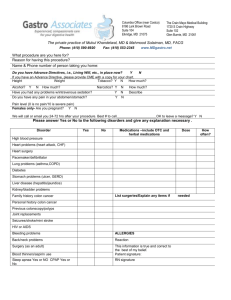

advertisement

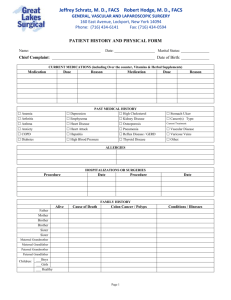

Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 34(1), September – October 2015; Article No. 28, Pages: 178-185 ISSN 0976 – 044X Review Article Digestive Disorder - Colon Cancer - Emphasising Celecoxib 1,2 1,3 1 1,2 2 2 *Arulraj P , Gopal V , Jeyabalan G , Kandasamy C S , Sam Johnson Udaya Chander , Venkatanarayanan R 1 Sunrise University, Rajasthan, India. 2 Dept of Pharmaceutics and Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, RVS College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Coimbatore, Tamil nadu, India. 3 Mother Theresa Post Graduate & Research Institute of Health Sciences, Pondicherry, Tamil nadu, India. *Corresponding author’s E-mail: arulraj.p@rvsgroup.com Accepted on: 18-07-2015; Finalized on: 31-08-2015. ABSTRACT As the way of life changes with foodstuff and society, the scheme of the body also get affected. The interior objective of this review article is to update and enrich the knowledge on colon and colonic cancer. Let the society understand and get rid of this disease. Authors, as they are researching with colon cancer and drug delivery system, being a healthcare team, would like to contribute the basic and phenomenal concept behind their area of research. Collected all the materials and research article from 1999 to 2015 related to colon cancer and a Comprehensive preliminary concepts were arranged. As many of the research articles, they have used bundle of drug candidates with the reports (Nimisulide, Ibuprofen, Diclofenac, Salbutamol, Metronidazole, etc). The recent trends and in the medicine net says to use Celecoxib as drug candidate for chronic condition of colon cancer. The ileum (last part of the small intestine) connects to the cecum (first part of the colon) in the inferior right abdomen. The rest of the colon is separated into four parts: The ascending colon travels up the right side of the abdomen. The transverse colon runs across the abdomen. The downward colon activities behind the left stomach. The sigmoid colon is a tiny bend of the colon, just prior to the rectum. The colon eliminates water, salt, and various nutrients forming stool. Muscles line the colon’s walls, squeezing its contents along. Billions of bacteria coat the colon and its contents, living in a strong stability with the organization. Colorectal cancer is due to the nonstandard development of cells that contain the facility to enter by force or multiply to further parts of the body. The authors in the current article gives reviews to researchers on colon and colonic cancer under different heads like, colon conditions, colon tests, Signs and symptoms, Cause, Inflammatory bowel disease, Genetics, Epigenetics, Macroscopy, Microscopy, Immunochemistry, Diagnosis, Prevention, Management, Lifestyle, Medication, Chemotherapy, Radiation therapy, Palliative care. Keywords: Colon cancer, Celecoxib, Treatment of colorectal cancer. INTRODUCTION T hreat factors for colorectal cancer consist of way of life, elder age, and innate genetic disorders. Other threat factors incorporate diet, smoking, alcohol, lack of physical movement, ancestors history of colon cancer and colon polyps, attendance of colon polyps, race, disclosure to emission, and even other diseases such as diabetes and obesity.1,2 Genetic disorders only occur in a small fraction of the residents. A diet high in red, processed meat, while low in fiber increases the risk of colorectal cancer.1 Other diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, can increase the risk of colorectal cancer.1 Some of the inherited hereditary disorders that can origin colorectal cancer include familial adenomatous polyposis and hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer; however, these represent less than 5% of cases.1,2 It typically starts as a benign tumor, frequently in the form of a polyp, which over time becomes cancerous.1 Bowel malignancy may be diagnosed by obtaining a sample of the colon during a sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.3 This is then followed by medical imaging to conclude if the disease has spread.1 Screening is effective for preventing and decreasing deaths from colorectal cancer. Screening is recommended starting from the age 4 of 50 to 75. During colonoscopy, small polyps may be removed if found. If a large polyp or tumor is found, a biopsy may be performed to check if it is cancerous. Aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs reduce the risk.4,5 Their general use is not recommended for this purpose, however, due to side effects.6 Treatments used for colorectal cancer may include some combination of surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy and targeted therapy.1 Cancers that are confined within the wall of the colon may be curable with surgery while cancer that has spread widely is usually not curable, with management focusing on improving quality of life and 1 symptoms. Five year survival rates in the United States are around 65%.7 This, however, depends on how advanced the cancer is, whether or not all the cancer can be removed with surgery, and the person’s overall health.3 Worldwide, colorectal cancer is the third most frequent type of cancer building up about 10% of all cases. In 2012 there were 1.4 million new cases and 694,000 deaths from the disease.8 It is more common in developed countries, where more than 65% of cases are found.4 It is less common in women than men.4 Colon Conditions Colitis: tenderness of the colon. provocative bowel disease or infections are the main common causes. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research Available online at www.globalresearchonline.net © Copyright protected. Unauthorised republication, reproduction, distribution, dissemination and copying of this document in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. 178 © Copyright pro Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 34(1), September – October 2015; Article No. 28, Pages: 178-185 Diverticulosis: tiny fragile areas in the colon’s muscular wall allocate the colon’s lining to protrude through, forming tiny pouches called diverticuli. Diverticuli regularly root no troubles, but can bleed or turn around into inflamed or infected. Diverticulitis: When diverticuli become inflamed or infected, diverticulitis results. Abdominal pain, fever, and constipation are ordinary symptoms. Colon bleeding (hemorrhage): Multiple potential colon problems can cause bleeding. Rapid bleeding is observable in the stool, but very slow bleeding might not be. Inflammatory bowel disease: A name for either Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. Both circumstances can cause colon inflammation (colitis). ISSN 0976 – 044X Sigmoidoscopy: An endoscope is inserted into the rectum and advanced through the left side of the colon. Sigmoidoscopy cannot be used to view the middle and right sides of the colon. Colon biopsy: During a colonoscopy, a small piece of colon tissue may be removed for testing. A colon biopsy can help diagnose cancer, infection, or inflammation.9 Colon Treatments Antidiarrheal agents: Various medicines can slow down diarrhea, reducing discomfort. Reducing diarrhea does not slow down recovery for most diarrheal illnesses. Stool softeners: Over-the-counter and prescription medicines can soften the stool; stool softeners can affect constipation, but not always. Crohn’s disease: An inflammatory situation that usually affects the colon and intestines. Abdominal pain and diarrhea (which may be bloody) are symptoms. Laxatives: Medicines and herbs and some salts can stimulate the bowel muscles or bring more water into the bowel to relieve constipation. Some laxatives are not safe with long term use. Ulcerative colitis: An inflammatory condition that usually affects the colon and rectum. Like Crohn’s disease, bloody diarrhea is a common symptom of ulcerative colitis. Enema: A term for pushing liquid into the colon through the anus. Enemas can deliver medicines to treat constipation or other colon conditions. Diarrhea: Stools that are frequent, loose, or watery are commonly called diarrhea. Most diarrhea is due to selflimited, mild infections of the colon or small intestine. Colonoscopy: Using tools on the tip of the endoscope, a doctor can treat certain colon conditions. Bleeding, polyps, or cancer might be treated by colonoscopy. Salmonellosis: The bacteria Salmonella can contaminate food and infect the intestine. Salmonella causes diarrhea and stomach cramps, which frequently resolve without treatment. Polypectomy: During colonoscopy, removal of a colon polyp is called polypectomy. Shigellosis: The bacteria Shigella can contaminate food and invade the colon. Symptoms include fever, stomach cramps, and diarrhea, which may be bloody. Travelers’ diarrhea: Many different bacteria commonly contaminate water or food in developing countries. Loose stools, sometimes with nausea and fever, are symptoms. Colon polyps: Polyps are small growths. Some of these develop into cancer, but it takes a long time. Removing them can prevent many colon cancers. Colon cancer: Cancer of the colon affects more than 100,000 Americans each year. Most colon cancer is 9 preventable through regular screening. Colon Tests Colon surgery: Using open or laparoscopic surgery, part or the entire colon may be removed (colectomy). This may be done for severe bleeding, cancer, or ulcerative colitis. Anti-inflammatory medicines: Various drugs can slow down immune system function, easing symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease. Antibiotics: Medicines can kill bacteria in the colon, used to cure some cases of colitis. Antibiotics may also be used for attacks of inflammatory bowel disease. Probiotics: Microbes are important for the health of the colon. Probiotics are supplements of healthy microbes which may have benefit for some conditions like Crohn’s 9 colitis. Signs and Symptoms Colonoscopy: An endoscope (flexible tube with a camera on its tip) is inserted into the rectum and advanced through the colon. A doctor can examine the entire colon with a colonoscope. Virtual colonoscopy: A test in which an X-ray machine and a computer create images of the inside of the colon. If problems are found, a traditional colonoscopy is usually needed. Stool occult blood testing: A test for blood in the stool. If blood is found in the stool, a colonoscopy may be needed to look for the source. The signs and symptoms of colorectal cancer depend on the location of the tumor in the bowel, and whether it has spread elsewhere in the body (metastasis). The classic warning signs include: worsening constipation, blood in the stool, decrease in stool caliber (thickness), loss of appetite, loss of weight, and nausea or vomiting in someone over 50 years old. While rectal bleeding or anemia are high-risk features in those over the age of 50, other commonly-described symptoms including weight loss and change in bowel habit are typically only 10-12 concerning if associated with bleeding. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research Available online at www.globalresearchonline.net © Copyright protected. Unauthorised republication, reproduction, distribution, dissemination and copying of this document in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. 179 © Copyright pro Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 34(1), September – October 2015; Article No. 28, Pages: 178-185 ISSN 0976 – 044X CAUSES Epigenetics Greater than 75-95% of colon cancer occurs in people with little or no genetic risk. Other risk factors include older age, male gender, high intake of fat, alcohol or red meat, obesity, smoking, and a lack of physical exercise. Approximately 10% of cases are linked to insufficient activity. The risk for alcohol appears to increase at greater than one drink per day. Drinking 5 glasses of water a day is linked to a decrease in the risk of colorectal cancer and 13-17 adenomatous polyps. Epigenetic alterations are much more frequent in colon cancer than genetic (mutational) alterations. As described by Vogelstein, an average cancer of the colon has only 1 or 2 oncogene mutations and 1 to 5 tumor suppressor mutations (together designated “driver mutations”), with about 60 further “passenger” mutations. Inflammatory bowel disease People with inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease) are at increased risk of colon cancer. The risk increases the longer a person has the disease, and the worse the severity of inflammation. In these high risk groups, both prevention with aspirin and regular colonoscopies are recommended. People with inflammatory bowel disease account for less than 2% of colon cancer cases yearly. In those with Crohn’s disease 2% get colorectal cancer after 10 years, 8% after 20 years, and 18% after 30 years. In those with ulcerative colitis approximately 16% develop either a cancer precursor or cancer of the colon over 30 years.18-20 Genetics Those with a family history in two or more first-degree relatives (such as a parent or sibling) have a two to threefold greater risk of disease and this group accounts for about 20% of all cases. A number of genetic syndromes are also associated with higher rates of colorectal cancer. The most common of these is hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC or Lynch syndrome) which is present in about 3% of people with colorectal cancer. Other syndromes that are strongly associated with colorectal cancer include Gardner syndrome, and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). For people with these syndromes, cancer almost always occurs and makes up to 1% of the cancer cases. A total proctocolectomy may be recommended for people with FAP as a preventative measure due to the high risk of malignancy. Colectomy, removal of the colon, may not suffice as a preventative measure because of the high risk 21-24 of rectal cancer if the rectum remains. Most deaths due to colon cancer are associated with metastatic disease. A gene that appears to contribute to the potential for metastatic disease, metastasis associated in colon cancer 1 (MACC1), has been isolated. It is a transcriptional factor that influences the expression of hepatocyte growth factor. This gene is associated with the proliferation, invasion and scattering of colon cancer cells in cell culture, and tumor growth and metastasis in mice. MACC1 may be a potential target for cancer intervention, but this possibility needs to be confirmed with clinical studies. Epigenetic factors, such as abnormal DNA methylation of tumor suppressor promoters play a 25-27 role in the development of colorectal cancer. However, by comparison, epigenetic alterations in colon cancers are frequent and affect hundreds of genes. For instance, there are types of small RNAs called microRNAs that are about 22 nucleotides long. These microRNAs (or miRNAs) do not code for proteins, but they can target protein coding genes and reduce their expression. Expression of these miRNAs can be epigenetically altered. As one example, the epigenetic alteration consisting of CpG island methylation of the DNA sequence encoding miR-137 reduces its expression. This is a frequent early epigenetic event in colorectal carcinogenesis, occurring in 81% of colon cancers and in 14% of the normal appearing colonic mucosa adjacent to the cancers. The altered adjacent tissues associated with these cancers are called field defects. Silencing of miR-137 can affect expression of about 500 genes, the targets of this miRNA. Changes in the level of miR-137 expression result in changed mRNA expression of the target genes by 2 to 20fold and corresponding, though often smaller, changes in expression of the protein products of the genes. Other microRNAs, with likely comparable numbers of target genes, are even more frequently epigenetically altered in colonic field defects and in the colon cancers that arise from them. These include miR-124a, miR-34b/c and miR342 which are silenced by CpG island methylation of their encoding DNA sequences in primary tumors at rates of 99%, 93% and 86%, respectively, and in the adjacent normal appearing mucosa at rates of 59%, 26% and 56%, respectively.28-32 In addition to epigenetic alteration of expression of miRNAs, other common types of epigenetic alterations in cancers that change gene expression levels include direct hypermethylation or hypomethylation of CpG islands of protein-encoding genes and alterations in histones and chromosomal architecture that influence gene expression.33,34 As an example, 147 hypermethylations and 27 hypomethylations of protein coding genes were frequently associated with colorectal cancers. Of the hypermethylated genes, 10 were hypermethylated in 100% of colon cancers, and many others were hypermethylated in more than 50% of colon cancers. In addition, 11 hypermethylations and 96 hypomethylations 35 of miRNAs were also associated with colorectal cancers. Recent evidence indicates that early epigenetic reductions of DNA repair enzyme expression likely lead to the genomic and epigenomic instability characteristic of 36-38 cancer. As summarized in the articles Carcinogenesis and Neoplasm, for sporadic cancers in general, a deficiency in International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research Available online at www.globalresearchonline.net © Copyright protected. Unauthorised republication, reproduction, distribution, dissemination and copying of this document in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. 180 © Copyright pro Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 34(1), September – October 2015; Article No. 28, Pages: 178-185 DNA repair is occasionally due to a mutation in a DNA repair gene, but is much more frequently due to epigenetic alterations that reduce or silence expression of DNA repair genes. Macroscopy Cancers on the right side of the large intestine (ascending colon and cecum) tend to be exophytic, that is, the tumor grows outwards from one location in the bowel wall. This very rarely causes obstruction of feces, and presents with symptoms such as anemia. Left-sided tumors tend to be circumferential, and can obstruct the bowel lumen, much like a napkin ring, and results in thinner caliber stools. Microscopy Adenocarcinoma is a malignant epithelial tumor, originating from superficial glandular epithelial cells lining the colon and rectum. It invades the wall, infiltrating the muscularis mucosae layer, the submucosa, and then the muscularis propria. Tumor cells describe irregular tubular structures, harboring pluristratification, multiple lumens, reduced stroma ("back to back" aspect). Sometimes, tumor cells are discohesive and secrete mucus, which invades the interstitium producing large pools of mucus/colloid (optically "empty" spaces). This occurs in mucinous (colloid) adenocarcinoma, in which cells are poorly differentiated. If the mucus remains inside the tumor cell, it pushes the nucleus at the periphery. This occurs in "signet-ring cell." Depending on glandular architecture, cellular pleomorphism, and mucosecretion of the predominant pattern, adenocarcinoma may present three degrees of differentiation: well, moderately, and poorly differentiated.39 ISSN 0976 – 044X Immunochemistry Most (50%) colorectal adenomas and (80-90%) colorectal cancer tumors are thought to over express the 40 cyclooxygenase-2(COX-2) enzyme. This enzyme is generally not found in healthy colon tissue, but is thought to fuel abnormal cell growth. PREVENTION Most colorectal cancers should be preventable, through increased surveillance and lifestyle changes.41,42 Lifestyle Current dietary recommendations to prevent colorectal cancer include increasing the consumption of whole grains, fruits and vegetables, and reducing the intake of red meat. The evidence for fiber and fruits and vegetables however is poor. Physical exercise is associated with a modest reduction in colon but not rectal cancer risk. Sitting regularly for prolonged periods is associated with higher mortality from colon cancer. The risk is not negated by regular exercise, though it is lowered.43-47 Medication Aspirin and Celecoxib appear to decrease the risk of colorectal cancer in those at high risk. Celecoxib matrix tablet with natural polysaccharide was found to be effective in controlling the colon cancer. However, it is not recommended in those at average risk. There is tentative evidence for calcium supplementation but it is not sufficient to make a recommendation. Vitamin D intake and blood levels are associated with a lower risk of colon cancer.48-53 Screening As more than 80% of colorectal cancers arise from adenomatous polyps, screening for this cancer is effective not only for early detection but also for prevention. Diagnosis of cases of colorectal cancer through screening tends to occur 2–3 years before diagnosis of cases with symptoms. Any polyps that are detected can be removed, usually by colonoscopy, and thus prevented from turning cancerous. Screening has the potential to reduce colorectal cancer deaths by 60%.54-55 Figure 1: inside of the colon showing one invasive colorectal carcinoma Figure 2: Endoscopy of colon cancer The three main screening tests are fecal occult blood 9 testing, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy. Of the three, only sigmoidoscopy cannot screen the right side of the colon where 42% of malignancies are found.56 Virtual colonoscopy via a CT scan appears as good as standard colonoscopy for detecting cancers and large adenomas but is expensive, associated with radiation exposure, and cannot remove any detected abnormal growths like standard colonoscopy can.9 Fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) of the stool is typically recommended every two years and can be either guaiac based or immunochemical.9 If abnormal FOBT results are found, participants are typically referred for a follow-up colonoscopy examination. Annual to biennial FOBT International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research Available online at www.globalresearchonline.net © Copyright protected. Unauthorised republication, reproduction, distribution, dissemination and copying of this document in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. 181 © Copyright pro Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 34(1), September – October 2015; Article No. 28, Pages: 178-185 screening reduce colorectal cancer mortality by 16% and among those participating in screening colorectal cancer mortality can be reduced up to 23%, although it has not been proven to reduce all-cause mortality. Immunochemical tests are highly accurate and do not require dietary or medication changes before testing.57,58 Medical societies in the United States typically recommend screening between the age of 50 and 75 years with sigmoidoscopy every 5 years and colonoscopy every 10 years. For those at high risk, screenings usually begin at around 40.9,59 It is unclear which of these two methods is better. Colonoscopy may find more cancers in the first part of the colon but is associated with greater cost and more complications. For people with average risk who have had a high-quality colonoscopy with normal results, the American Gastroenterological Association does not recommend any type of screening in the 10 60-62 years following the colonoscopy. For people over 75 or those with a life expectancy of less than 10 years, screening is not recommended. It takes about 10 years after screening for one out of a 1000 people to 63,64 benefit. Some countries have national colorectal screening programs which offer FOBT screening for all adults within a certain age group, typically starting between age 50 and 60. Examples of countries with organized screening include the United Kingdom, Australia and the Netherlands. MANAGEMENT ISSN 0976 – 044X If cancer has spread to the lymph nodes or distant organs, which is the case with stage III and stage IV colon cancer respectively, adding chemotherapy agents fluorouracil, capecitabine or oxaliplatin increases life expectancy. If the lymph nodes do not contain cancer, the benefits of chemotherapy are controversial. If the cancer is widely metastatic or unresectable, treatment is then palliative. Typically in this setting, a number of different chemotherapy medications may be used.9 Chemotherapy drugs for this condition may include capecitabine, fluorouracil, irinotecan, oxaliplatin and UFT. The drugs capecitabine and fluorouracil are interchangeable, with capecitabine being an oral medication while fluorouracil being an intravenous medicine. Antiangiogenic drugs such as bevacizumab are often added in first line therapy. Another class of drugs used in the second line setting are epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, of which the two FDA approved ones are cetuximab and panitumumab. Use of Celecoxob in combination with natural polysaccharide may be given for the case of chronic conditions colon cancer.53 The primary difference in the approach to low stage rectal cancer is the incorporation of radiation therapy. Often, it is used in conjunction with chemotherapy in a neo adjuvant fashion to enable surgical resection, so that ultimately as colostomy is not required. However, it may not be possible in low lying tumors, in which case, a permanent colostomy may be required. Stage IV rectal cancer is treated similar to stage IV colon cancer. Radiation Therapy The treatment of colorectal cancer can be aimed at cure or palliation. The decision on which aim to adopt depends on various factors, including the person’s health and preferences, as well as the stage of the tumor.65 When colorectal cancer is caught early, surgery can be curative. However, when it is detected at later stages (for which metastases are present), this is less likely and treatment is often directed at palliation, to relieve symptoms caused by the tumour and keep the person as comfortable as possible. Treatment of colon cancer also depends on the number and nature of the microorganism present in the 66,67 colon. While a combination of radiation and chemotherapy may be useful for rectal cancer,9 its use in colon cancer is not routine due to the sensitivity of the bowels to radiation.68,69 Just as for chemotherapy, radiotherapy can be used in the neo adjuvant and adjuvant setting for some stages of rectal cancer. Palliative care Chemotherapy Palliative care is medical care which focuses on treatment of symptoms from serious illness, like cancer, and 70 improving quality of life. Palliative care is recommended for any person who has advanced colon cancer or has 71 significant symptoms. In both cancer of the colon and rectum, chemotherapy may be used in addition to surgery in certain cases. The decision to add chemotherapy in management of colon and rectal cancer depends on the stage of the disease. Involvement of palliative care may be beneficial to improve the quality of life for both the person and his or her family, by improving symptoms, anxiety and preventing admissions to the hospital.72 In Stage I colon cancer, no chemotherapy is offered, and surgery is the definitive treatment. The role of chemotherapy in Stage II colon cancer is debatable, and is usually not offered unless risk factors such as T4 tumor or inadequate lymph node sampling is identified. It is also known that the patients who carry abnormalities of the mismatch repair genes do not benefit from chemotherapy. For stage III and Stage IV colon cancer, 9 chemotherapy is an integral part of treatment. In people with incurable colorectal cancer, palliative care can consist of procedures that relieve symptoms or complications from the cancer but do not attempt to cure the underlying cancer, thereby improving quality of life. Surgical options may include non-curative surgical removal of some of the cancer tissue, bypassing part of the intestines, or stent placement. These procedures can be considered to improve symptoms and reduce complications such as bleeding from the tumor, International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research Available online at www.globalresearchonline.net © Copyright protected. Unauthorised republication, reproduction, distribution, dissemination and copying of this document in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. 182 © Copyright pro Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 34(1), September – October 2015; Article No. 28, Pages: 178-185 73 abdominal pain and intestinal obstruction. Nonoperative methods of symptomatic treatment include radiation therapy to decrease tumor size as well as pain 74 medications. Acknowledgement: We incredibly grateful to Chairman Dr. K.V. Kupusamy, Managing Trustee Mr. K. Senthil Ganesh, Secretary Dr. H. Mohamed Mubarak, Chief Executive Mr. Natrajan of RVS Educational Trust, Principal Dr. R. Venkatanarayanan, Research Director Dr. R. Manavalan, Teachers, Students of RVS College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Sulur, Coimbatore, Chancellor, Pro Chancellor, Vice Chancellor of Sunrise University, Rajasthan for providing support and Prof. Dr. V. Gopal, Principal, College of Pharmacy, Mother Theresa Post Graduate & Research Institute of Health Sciences, Pondicherry, Dr. G. Jeyabalan, Principal, Alwar College of Pharmacy, Alwar, Rajasthan for their valuable guidance during this research work. REFERENCES 1. World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.5. 2. National Cancer Institute. 2014-02-27. Retrieved 29 June 2014. 3. National Cancer Institute. 2014-05-12. Retrieved 29 June 2014. 4. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. October 2008. Retrieved 29 June 2014. 5. Current oncology reports 15(6), 533–40. 6. Am Family Physician 76(1), 2007, 109–13. 7. NCI. Retrieved 18 June 2014 8. World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 1.1 9. http//www.medicinenet.com 10. Tadataka Yamada ; associate editors, David H. Alpers et (2008). Principles of clinical gastroenterology. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 381 11. Astin M, Griffin T, Neal RD, Rose P, Hamilton W (May 2011). "The diagnostic value of symptoms for colorectal cancer in primary care: a systematic review". The British journal of general practice: the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 61(586), 231–43 12. Adelstein BA, Macaskill P, Chan SF, Katelaris PH, Irwig L (2011). "Most bowel cancer symptoms do not indicate colorectal cancer and polyps: a systematic review". BMC gastroenterology 11, 65. 13. Watson AJ, Collins PD (2011). "Colon cancer: a civilization disorder". Digestive diseases (Basel, Switzerland) 29(2), 222–8. 14. Cunningham D, Atkin W, Lenz HJ, Lynch HT, Minsky B, Nordlinger B, Starling N (2010). "Colorectal cancer". Lancet 375(9719), 2010, 1030–47. 15. Shiroma, Eric J; Lobelo, Felipe; Puska, Pekka; Blair, Steven N; Katzmarzyk, Peter T (1 July 2012)."Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: ISSN 0976 – 044X an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy". The Lancet, 380(9838), 2012, 219–29. 16. Fedirko V, Tramacere I, Bagnardi V, Rota M, Scotti L, Islami F, Negri E, Straif K, Romieu I, La Vecchia C, Boffetta P, Jenab M (Sep 2011). "Alcohol drinking and colorectal cancer risk: an overall and dose-response meta-analysis of published studies". Annals of Oncology, 22(9), 2011, 1958–72. 17. Valtin H (November 2002). ""Drink at least eight glasses of water a day." Really? Is there scientific evidence for "8 x 8"?" American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology 283(5), 2002, R993–1004. 18. Jawad N Direkze N, Leedham SJ (2011). "Inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer". Recent results in cancer research. Fortschritte der Krebsforschung. Progres dans les recherches sur le cancer. Recent Results in Cancer Research 185, 2011, 99–115. 19. Xie J, Itzkowitz, SH (2008). "Cancer in inflammatory bowel disease". World journal of gastroenterology : WJG14 (3), 2008, 378–89. 20. Triantafillidis JK, Nasioulas G, Kosmidis PA (Jul 2009). "Colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, risk factors, mechanisms of carcinogenesis and prevention strategies". Anticancer research, 29(7), 2009, 2727–37. 21. Triantafillidis JK, Nasioulas, G, Kosmidis, PA (Jul 2009). "Colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, risk factors, mechanisms of carcinogenesis and prevention strategies". Anticancer research, 29(7), 2009, 2727–37. 22. Juhn E, Khachemoune A (2010). "Gardner syndrome: skin manifestations, differential diagnosis and management". American journal of clinical dermatology, 11(2), 2010, 117– 22. 23. Half E, Bercovich D, Rozen P (2009). "Familial adenomatous polyposis". Orphanet journal of rare diseases 4, 2009, 22. 24. Möslein G, Pistorius S, Saeger H-, Schackert HK (February 2003). "Preventive surgery for colon cancer in familial adenomatous polyposis and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome". Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 388(1), 2003, 9–16. 25. Stein, Ulrike; Walther, Wolfgang; Arlt, Franziska; Schwabe, Holger; Smith, Janice; Fichtner, Iduna; Birchmeier, Walter; Schlag, Peter M (2008). "MACC1, a newly identified key regulator of HGF-MET signaling, predicts colon cancer metastasis". Nature Medicine, 15(1), 2008, 59–67. 26. Stein U (2013) MACC1 - a novel target for solid cancers. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 27. Scheubel K, Chen W, Cope L. (2007). "Comparing the DNA Hypermethylome with Gene Mutations in Human Colorectal Cancer". PLoS Genetics, 3(9), 2007, e157. 28. Vogelstein, B; Papadopoulos, N; Velculescu, VE; Zhou, S; Diaz Jr, LA; Kinzler, KW (2013). "Cancer genome landscapes". Science, 339(6127), 2013, 1546–58. 29. Lochhead P, Chan AT, Nishihara R, Fuchs CS, Beck AH, Giovannucci E, Ogino S. Etiologic field effect: reappraisal of the field effect concept in cancer predisposition and progression. Mod Pathol, 2014. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research Available online at www.globalresearchonline.net © Copyright protected. Unauthorised republication, reproduction, distribution, dissemination and copying of this document in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. 183 © Copyright pro Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 34(1), September – October 2015; Article No. 28, Pages: 178-185 30. Balaguer F, Link A, Lozano J. (August 2010). "Epigenetic silencing of miR-137 is an early event in colorectal carcinogenesis". Cancer Res. 70(16), 2010, 6609–18. 31. Deng, G; Kakar, S; Kim, YS (2011). "MicroRNA-124a and microRNA-34b/c are frequently methylated in all histological types of colorectal cancer and polyps, and in the adjacent normal mucosa". Oncology letters, 2(1), 2011, 175–180. 32. Grady, WM; Parkin, RK; Mitchell, PS; Lee, JH; Kim, YH; Tsuchiya, KD; Washington, MK; Paraskeva, C; Willson, JK; Kaz, AM; Kroh, EM; Allen, A; Fritz, BR; Markowitz, SD; Tewari, M (2008). "Epigenetic silencing of the intronic microRNA hsa-miR-342 and its host gene EVL in colorectal cancer". Oncogene, 27(27), 2008, 3880–8. 33. Kanwal, R; Gupta, S (2012). "Epigenetic modifications in cancer". Clinical genetics, 81(4), 2012, 303–11. 34. Baldassarre, G; Battista, S; Belletti, B; Thakur, S; Pentimalli, F; Trapasso, F; Fedele, M; Pierantoni, G; Croce, CM; Fusco, A (2003). "Negative regulation of BRCA1 gene expression by HMGA1 proteins accounts for the reduced BRCA1 protein levels in sporadic breast carcinoma". Molecular and Cellular Biology, 23(7), 2003, 2225–38. 35. Schnekenburger, M; Diederich, M (2012). "Epigenetics Offer New Horizons for Colorectal Cancer Prevention".Current colorectal cancer reports, 8(1), 2012, 66–81. 36. Jacinto FV, Esteller M (July 2007). "Mutator pathways unleashed by epigenetic silencing in human cancer". Mutagenesis, 22(4), 2007, 247–53. 37. Lahtz C, Pfeifer GP (February 2011). "Epigenetic changes of DNA repair genes in cancer". J Mol Cell Biol, 3(1), 2011, 51– 8. 38. Bernstein C, Nfonsam V, Prasad AR, Bernstein H (March 2013). "Epigenetic field defects in progression to cancer". World J Gastrointest Oncol, 5(3), 2013, 43. 39. Pathology atlas 40. Sostres C, Gargallo CJ, Lanas A (February 2014)."Aspirin, cyclooxygenase inhibition and colorectal cancer". World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther, 5(1), 2014, 40. 41. Searke, David (2006). Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 809. 42. Rennert, Gad (2007). Cancer Prevention. Springer. p. 179. 43. Campos FG, Logullo Waitzberg, AG, Kiss, DR, Waitzberg, DL, Habr-Gama, A, Gama-Rodrigues, J (Jan 2005). "Diet and colorectal cancer: current evidence for etiology and prevention". Nutricion hospitalaria : organo oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Nutricion Parenteral y Enteral 20(1), 2005, 18–25. 44. Doyle VC, Logullo Waitzberg, AG, Kiss, DR, Waitzberg, DL, Habr-Gama, A, Gama-Rodrigues, J (May 2007). "Nutrition and colorectal cancer risk: a literature review". Gastroenterology nursing: the official journal of the Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates, 30(3), 2007, 178–82; quiz 182–3. 45. Harriss DJ, Atkinson G, Batterham A, George K, Cable NT, Reilly T, Haboubi N, Renehan AG, Colorectal Cancer, Lifestyle, Exercise And Research, Group (Sep 2009). ISSN 0976 – 044X "Lifestyle factors and colorectal cancer risk (2): a systematic review and meta-analysis of associations with leisure-time physical activity". Colorectal disease: the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland, 11(7), 2009, 689–701. 46. Robsahm TE, Aagnes B, Hjartåker A, Langseth H, Bray FI, Larsen IK (November 2013). "Body mass index, physical activity, and colorectal cancer by anatomical subsites: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies." Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 22(6), 492–505. 47. Biswas A, Oh PI, Faulkner GE, Bajaj RR, Silver MA, Mitchell MS. (2015). "Sedentary Time and Its Association With Risk for Disease Incidence, Mortality, and Hospitalization in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine, 162(2), 2015, 123–32. 48. Cooper K, Squires H, Carroll C, Papaioannou D, Booth A, Logan RF, Maguire C, Hind D, Tappenden P (Jun 2010). "Chemoprevention of colorectal cancer: systematic review and economic evaluation". Health technology assessment (Winchester, England), 14(32), 2010, 1–206. 49. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. "Aspirin or Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs for the Primary Prevention of Colorectal Cancer". United States Department of Health & Human Services. 2010/2011. 50. Weingarten MA, Zalmanovici A, Yaphe J (2008). Weingarten, Michael Asher MA, ed. "Dietary calcium supplementation for preventing colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1) 51. Ma Y, Zhang, P, Wang, F, Yang, J, Liu, Z, Qin, H (2011). "Association between vitamin D and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review of prospective studies". Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 29(28), 2011, 3775–82. 52. Yin L, Grandi N, Raum E, Haug U, Arndt V, Brenner H (Jul 2011). "Meta-analysis: Serum vitamin D and colorectal adenoma risk". Preventive medicine, 53(1–2), 2011, 10–6. 53. Arulraj P, Gopal V, Jeyabalan G, Kandasamy C S, Sam Johnson Udaya Chander, Venkatanarayanan R. Studies on formulation development and in vitro evaluation of Celecoxib matrix tablet containing Amylose and pectin as natural polysaccharides for colon specific drug delivery. World journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Issue 4, Volume 7, 2015, P 1247-52. 54. "What Can I Do to Reduce My Risk of Colorectal Cancer?" Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 2, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2015. 55. He J, Efron JE (2011). "Screening for colorectal cancer". Advances in surgery, 45, 2011, 31–44. 56. Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A (Mar 2012). "Trends in Colorectal Cancer Incidence Rates in the United States by Tumor Location and Stage, 1992–2008". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 21(3), 2012, 411– 6. Retrieved September 16, 2012. 57. Hewitson, P; Glasziou, P; Watson, E; Towler, B; Irwig, L (June 2008). "Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): an update". The American journal of gastroenterology, 103(6), 1541–9. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research Available online at www.globalresearchonline.net © Copyright protected. Unauthorised republication, reproduction, distribution, dissemination and copying of this document in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. 184 © Copyright pro Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 34(1), September – October 2015; Article No. 28, Pages: 178-185 ISSN 0976 – 044X 58. Lee, Jeffrey K.; Liles, Elizabeth G.; Bent, Stephen; Levin, Theodore R.; Corley, Douglas A. (4 February 2014). "Accuracy of Fecal Immunochemical Tests for Colorectal Cancer". Annals of Internal Medicine, 160(3), 2014, 171– 181. 66. Arulraj P, Saraswathy R, Gopal V, Nair R, Kandasamy C S, Venkatanarayanan R. Microbial approach of rat colonic Microflora – A dangerous stringent anaerobe for targeting to colon. International Journal of Research in Ayurveda & Pharmacy, Volume 1, Issue I, Sep – Oct 2010, p.135-139 59. "Screening for Colorectal Cancer". U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2008. 67. Arulraj P, Saraswathy R, Chandini Nair R, B S Nath., VKSM Subramanyam M, Venkatanarayanan R. Isolation and characterization of rat colonic Microflora for targeting to colon. International Journal of Pharma and BioSciences. Vol 1, Issue 4, Oct-Dec 2010. P 597-600 60. Brenner, H.; Stock, C.; Hoffmeister, M. (9 April 2014). "Effect of screening sigmoidoscopy and screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies". BMJ 348 (apr09 1): g2467–g2467. 61. American Gastroenterological Association. "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF).Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation (American Gastroenterological Association). Retrieved August 17, 2012. 62. Winawer, S; Fletcher, R; Rex, D; Bond, J; Burt, R; Ferrucci, J; Ganiats, T; Levin, T; Woolf, S; Johnson, D; Kirk, L; Litin, S; Simmang, C; Gastrointestinal Consortium, Panel (February 2003). "Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence". Gastroenterology 124(2), 2003, 544–60. 63. Qaseem A, Denberg TD, Hopkins RH Jr (2012)."Screening for Colorectal Cancer: A Guidance Statement From the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine 156(5), 2012, 378–386. 64. Tang, V; Boscardin, WJ; Stijacic-Cenzer, I; Lee, SJ (16 April 2015). "Time to benefit for colorectal cancer screening: survival meta-analysis of flexible sigmoidoscopy trials." BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 350, 2015, 9. 65. Stein A, Atanackovic, D, Bokemeyer, C (Sep 2011). "Current standards and new trends in the primary treatment of colorectal cancer". European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 47 Suppl 3, 2011, S312–4. 68. Vincent T. DeVita, Jr., Theodore S. Lawrence, Steven A. Rosenberg ; associate scientific advisors, Robert A. Weinberg, Ronald A. DePinho ; with 421 contributing (2008). DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg’s cancer : principles & practice of oncology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1258. 69. Vincent T. DeVita, Jr., Theodore S. Lawrence, Steven A. Rosenberg ; associate scientific advisors, Robert A. Weinberg, Ronald A. DePinho ; with 421 contributing (2008). DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg’s cancer : principles & practice of oncology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1258. 70. "Palliative or Supportive Care". American Cancer Society. Retrieved 20 August 2014. 70. "ASCO Provisional Clinical Opinion: The Integration of Palliative Care into Standard Oncology Care". ASCO. Retrieved 20 August 2014. 71. Higginson, IJ; Evans, CJ (Sep–Oct 2010). "What is the evidence that palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients and their families?". Cancer journal (Sudbury, Mass.) 16(5), 2010, 423–35. 72. Wasserberg N, Kaufman HS (December 2007). "Palliation of colorectal cancer". Surg Oncol 16(4), 2007, 299–310. 73. Amersi F, Stamos MJ, Ko CY (July 2004). "Palliative care for colorectal cancer". Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 13(3), 2004, 467–77. Source of Support: Nil, Conflict of Interest: None. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research Available online at www.globalresearchonline.net © Copyright protected. Unauthorised republication, reproduction, distribution, dissemination and copying of this document in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. 185 © Copyright pro