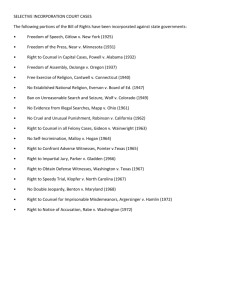

Gideon “Equitable” Right to Counsel in Habeas Corpus

advertisement