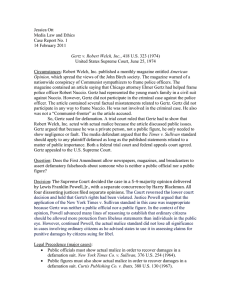

What’s It to You: The First Amendment and I.

advertisement