The Context of Ideology: Law, Politics, and Empirical Legal Scholarship

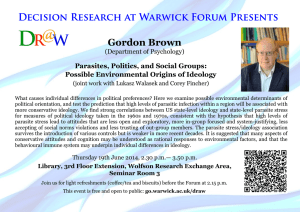

advertisement