Why Doctors Shouldn’t Practice Law: The American Medical Association’s Misdiagnosis of Physician

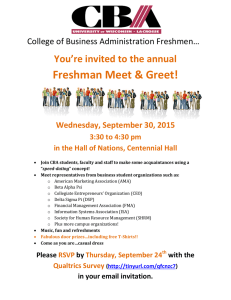

advertisement