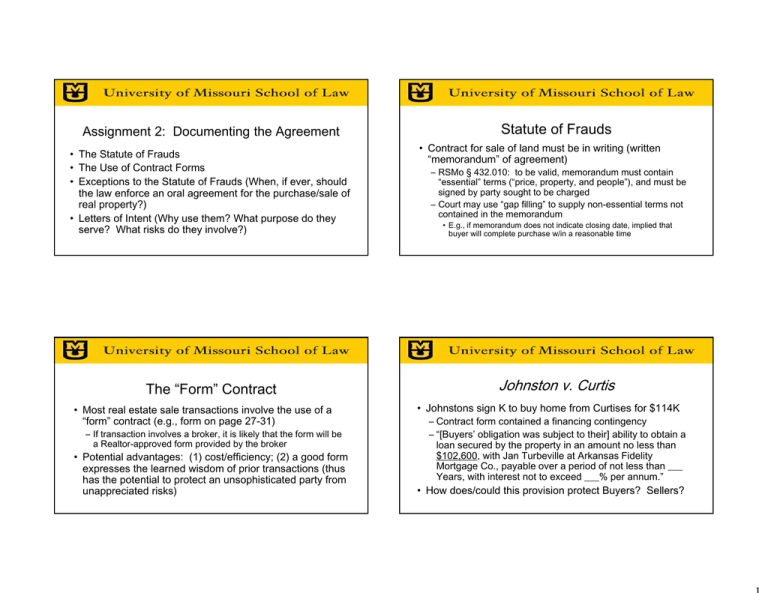

Statute of Frauds Assignment 2: Documenting the Agreement

advertisement

Assignment 2: Documenting the Agreement • The Statute of Frauds • The Use of Contract Forms • Exceptions to the Statute of Frauds (When, if ever, should the law enforce an oral agreement for the purchase/sale of real property?) • Letters of Intent (Why use them? What purpose do they serve? What risks do they involve?) The “Form” Contract • Most real estate sale transactions involve the use of a “form” contract (e.g., form on page 27-31) – If transaction involves a broker, it is likely that the form will be a Realtor-approved form provided by the broker • Potential advantages: (1) cost/efficiency; (2) a good form expresses the learned wisdom of prior transactions (thus has the potential to protect an unsophisticated party from unappreciated risks) Statute of Frauds • Contract for sale of land must be in writing (written “memorandum” of agreement) – RSMo § 432.010: to be valid, memorandum must contain “essential” terms (“price, property, and people”), and must be signed by party sought to be charged – Court may use “gap filling” to supply non-essential terms not contained in the memorandum • E.g., if memorandum does not indicate closing date, implied that buyer will complete purchase w/in a reasonable time Johnston v. Curtis • Johnstons sign K to buy home from Curtises for $114K – Contract form contained a financing contingency – “[Buyers’ obligation was subject to their] ability to obtain a loan secured by the property in an amount no less than $102,600, with Jan Turbeville at Arkansas Fidelity Mortgage Co., payable over a period of not less than ___ Years, with interest not to exceed ___% per annum.” • How does/could this provision protect Buyers? Sellers? • When house appraised for only $110K, Arkansas Fidelity Mortgage refused to make the loan – This relieved Johnston of the obligation to perform the contract at the $114K price (i.e., they had “overpaid”) • Parties then orally agreed to reduce price to $110K – Johnstons took possession pre-closing, and paid $500 – Johnstons got approved for a mortgage loan, but at a higher interest rate (10.75%) than Johnstons wanted to pay • Curtises sue to enforce the oral agreement to buy at $110K. Should Statute of Frauds prohibit its enforcement? The Part Performance Doctrine • Courts can enforce oral agreement, despite SoF, in cases of “part performance” of the oral agreement • Acts of part performance provide objective confirmation of the parties’ oral agreement • Part performance typically requires two of the following: – Buyer pays part or all of purchase price – Buyer goes into possession of land – Buyer makes substantial improvements to land Johnston v. Curtis • Held: Johnstons were bound to complete purchase at price of $110,000 – Their acts of part performance of the oral agreement (taking possession and payment of $500 toward price) took the oral agreement outside the Statute of Frauds • Having failed to perform, Johnstons were thus liable to Curtises for damages for breach of the agreement (including expectation damages and costs of resale) Johnston v. Curtis • Do you think the court gets the Johnston case right? Or should the court have refused to use part performance doctrine to enforce the oral agreement? • Critique: M/M Johnston did not have legal counsel in this transaction, and no broker was involved – Contingency provision in original K, if completed, would have been sufficient to protect the Johnstons – If they’d had professional advice, more likely that “blanks” in the financing contingency would’ve been filled in (i.e., maximum acceptable interest rate, shortest acceptable loan period) – Taking agreement outside SoF (enforcing oral agreement) ends up binding them to an unfavorable agreement entered into without professional advice – Query: what if Bank had only approved them for loan at 22%? Problem 2 • 7/12: Hickey orally offers to buy a home from Green for $150K; Green orally agrees to sell – Hickey gives Green a check for $2,000, marked “Deposit on Lot 1” (but Green does not deposit it) – Hickey then sells his existing house – No written contract was ever signed • 7/24: Green sells Lot 1 to X for $160K • Hickey sues Green for breach of contract • Those who advocate for a “strict” view of the Statute of Frauds argue that cases like Johnston are bad as a policy matter – Enforcing such oral agreements, especially if one or both parties didn’t obtain professional help, just encourages more such agreements – We don’t want to encourage such agreements; in fact, we should want to channel unsophisticated purchasers toward getting professional advice • Counterpoint: making an example of Johnstons (by taking case outside SoF) could also warn future buyers to be more careful (and thus may encourage buyers to seek professional assistance) Problem 2: Is the Statute of Frauds Satisfied? • Check ≠ sufficient memorandum – It identifies the land and is signed by Hickey, but – It is not signed by seller Green (who is the party sought to be bound to the agreement by Hickey) • What if Green had cashed the check? – Endorsement = Green’s signature, but check still didn’t show the agreed price (which is an essential term) Estoppel (Reliance) • Restatement (2d) Contracts § 129: land sale contract may be enforced, despite noncompliance with Statute of Frauds, if “it is established that the party seeking enforcement, in reasonable reliance on the contract and on the continuing assent of the party against whom enforcement is sought, has so changed his position that injustice can be avoided only by specific enforcement” • Policy: refusing to enforce oral agreement, even if admitted, incentivizes parties to make written agreements • If people need written agreements, they’ll be more likely to go to professionals (brokers, lawyers) to get help (forms) • Forms will deal with unanticipated problem areas; SoF can thus serve a protective “channeling” function (forces people to better consider/evaluate the risks involved in buying land) • Hickey v. Green (Mass. 1982): on these facts, court allowed Hickey to enforce oral agreement against Green • Court noted: – Hickey had relied upon oral agreement to his detriment by selling his existing home – Green admitted existence and terms of oral agreement • If Green admitted the oral agreement and Hickey relied on it, is there any sound reason for a court to refuse to enforce the oral agreement? Letters of Intent • In commercial transactions, the parties often execute a “Letter of Intent” at the start of the process – Letter of Intent typically includes the essential terms of a proposed agreement • If one of the parties later withdraws from the transaction, can the other party argue that the Letter of Intent was an enforceable contract that has been breached? Problem 6 • Buffett and Trump sign “Letter of Intent” for Buffett to buy Trump Craft Brewery for $3.2MM • Jay-Z later offers Trump $4MM; Trump then refuses to sign a final contract of sale with Buffett, and sells Trump Craft Brewery to Jay-Z • Did the Letter of Intent constitute an enforceable agreement for which Buffett can sue Trump for breach? Letters of Intent • What’s the point of including the language making the LOI “nonbinding” [¶ 8]? Is that language effective? If the LOI is “nonbinding,” then what’s the point of executing it? • When Trump withdraws, can Buffett argue that the LOI is still enforceable based on reliance/estoppel? How can Trump avoid the risk of a court enforcing LOI despite this “nonbinding” language? Letter of Intent: “Nonbinding”? • ¶ 8: “The provisions of this Letter of Intent are subject to the execution of a formal agreement by the parties within a specified time in Paragraph 5 above and this Letter of Intent shall not be binding on Buyer or Seller until complete execution of such Purchase and Sale Agreement by the parties, which Purchase and Sale Agreement shall embody the above provisions and contain acceptable covenants and agreements regarding title, survey, closing procedures and expenses, notice, remedies, and such other items as may be deemed necessary or appropriate.” Letters of Intent • Generally, courts treat LOIs containing provisions such as ¶ 8 as being nonbinding – Rationale: many points/issues that may not be “essential terms” (price, property, parties), as that term is understood in the Statute of Frauds, are in fact “essential” to the parties to the LOI • E.g., representations/warranties from Seller to Buyer regarding property condition, title, etc. (Trump: “I can’t evaluate whether $3.2 is really an acceptable price without such matters being resolved and documented by lawyers, so I can’t be bound until then”) – Rationale: nonbinding LOI is less disruptive of Trump’s marketing efforts (can more readily field offers from other prospective buyers) Letters of Intent • Though nonbinding, LOIs often serve the role of signaling to professionals (such as lawyers) to begin transaction drafting – E.g., Buyer’s lawyer may use LOI to “fill in some of the blanks” in a comprehensive proposed purchase and sale agreement, which will thereafter be negotiated and modified to address key issues not addressed by LOI Letters of Intent • Does Trump face a meaningful risk that a court might enforce the LOI as a binding agreement based on Buffett’s reliance (estoppel), despite language of ¶ 8? • How might Trump better protect against this risk?