Early Modern Women Poets (1520-1700): ... Jane Stevenson and Peter Davidson ... Press, 2001), lii + 585pp, ISBN 0199242577

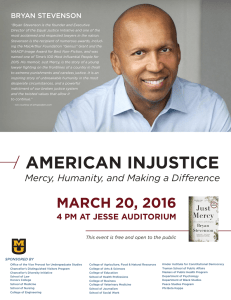

advertisement

Early Modern Women Poets (1520-1700): An Anthology, edited by Jane Stevenson and Peter Davidson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), lii + 585pp, ISBN 0199242577 Jane Stevenson and Peter Davidson’s Early Modern Women Poets is a much-anticipated and impressive new resource, the result of several years’ delving, transcribing, and researching during the two scholars’ years at Warwick. Early Modern Women Poets anthologises the verse of women who wrote in England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland between the years 1520 and 1700; crucially, it draws on a new and wide range of printed, manuscript and epigraphic sources. Women’s writing in the early modern period is a field of which our cartography has changed and expanded rapidly over the last twenty years. Virginia Woolf’s assumption that women were silent before Aphra Behn was proved wrong by Germaine Greer et al.’s anthology, Kissing the Rod (1988), and the critical studies of Margaret Ezell, Elaine Hobby and others; in the 1990s, Nottingham Trent University’s Perdita Project has begun to catalogue all manuscripts associated with women in the period. Stevenson and Davidson step off from this work and add to it very substantially. Isabella Whitney, Lady Mary Wroth, An Collins and Mary Astell are among the more familiar poets whose work is anthologised; alongside them are women as diverse as the six-year-old Catholic Anna Alcox, the prophetic pedlar Jane Hawkins, and the royalist gentlewoman Hester Pulter. Stevenson and Davidson also include Greek and Latin verse by Mildred Cecil (née Cooke), Lady Mary Cheke, Elizabeth Jane Leon (née Weston) and others, illustrating their introductory assertion that these languages 'were less of a male monopoly than they are sometimes thought to be'. Greek, Latin and French are not the only languages represented; Stevenson and Davidson expand our perceptions of verse by women in early modern Britain even further, including verse from the ethnically and linguistically distinct Celtic provinces. The diversity of the material they have uncovered and selected enables them in their introduction to negate sweepingly Elaine Showalter’s superficial suggestion that ‘English women’s writing, until the past few decades, was racially homogenous and regionally compact, with little ethnic, religious, or even class diversity’. Stevenson and Davidson arrange their anthology chronologically, although it is inevitable that exact dates for women’s lives or writings are not always clear. Each woman’s verse is preceded by a biographical and contextual note, and in several cases, such as that of Anna Ley (née Norman), these notes constitute important contributions to evolving biographies. Stevenson and Davidson's texts are conservatively modernised: only u/v and i/j spellings are normalised, and skeletal punctuation only is added to sparsely-punctuated manuscript texts. This proves to be an effective editorial middle road: the texts produced are clear and user-friendly, and annotation, at the end of each poem, is full without being intrusive. Printed and manuscript sources are detailed fully in an appendix to the volume. Stevenson and Davidson’s anthology is a vital contribution to early modern literary scholarship, making a comprehensive and hugely updated selection of verse texts authored by early modern women available in a major-press paperback. The clarity of its texts cater for a relatively general readership and, in addition, its scholarly framework renders it a summation of scholarly work on early modern female versifiers to date, and a starting point for further investigation. Stevenson and Davidson’s acknowledgement of Germaine Greer’s help and advice in the preparation of the volume is fitting. Early Modern Women Poets is Kissing the Rod two decades on; it should become the new text from which undergraduates are taught, as well as the handbook for current and future scholars in the field. Sarah Ross University of Warwick