Getting Away with Murder (Most of the Boone County, Missouri –

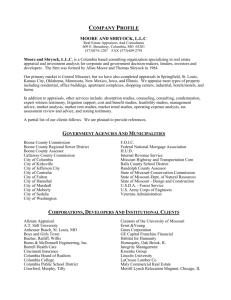

advertisement