ater Resources Research Institute Willamette River: River Lands and River Boundaries

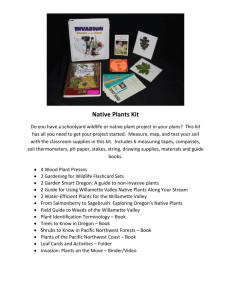

advertisement