T 1903

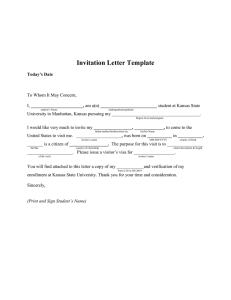

advertisement