Crops Small Grain Historical Document Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station

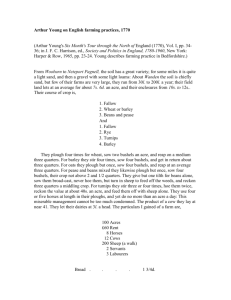

advertisement