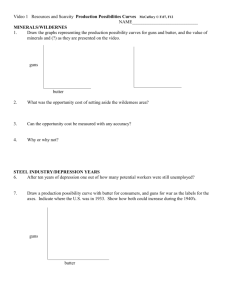

The Marketing Butter. Kansas

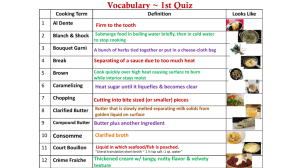

advertisement