REVISION IN TAX KANSAS Historical Document

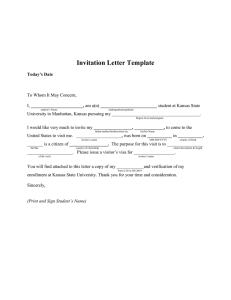

advertisement