Historical Document Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station

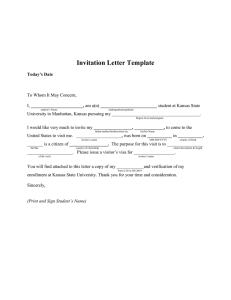

advertisement