GROWING AN ORCHARD IN KANSAS AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION AND APPLIED SCIENCE

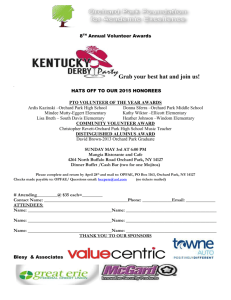

advertisement