Results Bindweed Control Experiments at the Fort Hays Branch Station, Kansas,

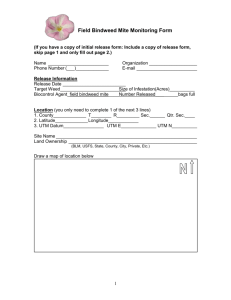

advertisement