SHEEP IN KANSAS PRODUCTION

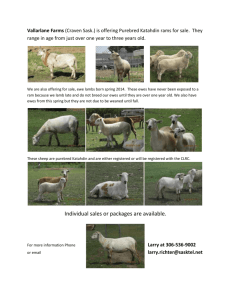

advertisement