TRANSPORTATION OF LIVESTOCK BY MOTOR TRUCK Historical Document

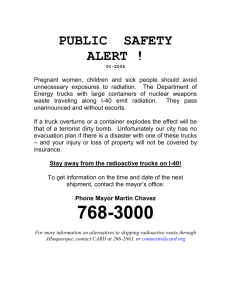

advertisement