Family Matters Understanding families in an Age of Austerity

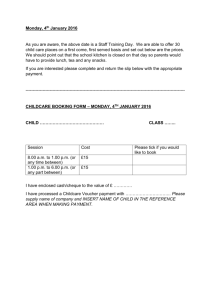

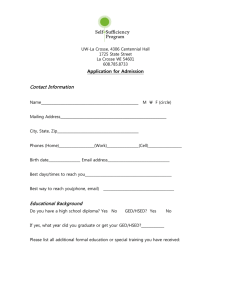

advertisement