Television Without Frontiers? Report with Evidence HOUSE OF LORDS

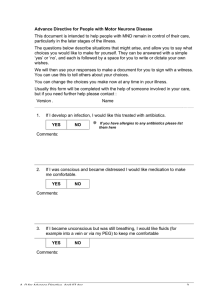

advertisement