International Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & Management... Web Site: www.ijaiem.org Email: , Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013

International Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & Management (IJAIEM)

Web Site: www.ijaiem.org Email: editor@ijaiem.org, editorijaiem@gmail.com

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013 ISSN 2319 - 4847

Automated System for Criminal Identification

Using Fingerprint Clue Found at Crime Scene

Manish P.Deshmukh

1

, Prof (Dr) Pradeep M.Patil

2

1 Associate Professor, E&TC Department, SSBT’s COET, Bambhori, Jalgaon

2 Director, RMD STIC , Warje, Pune - 58

Abstract

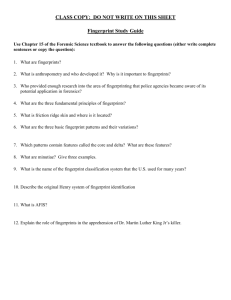

Criminal identification based on explicit detection of complete ridge structures in the fingerprint is difficult to extract automatically. Local ridge structures cannot be completely characterized by minutiae. Further, a minutia e based matching has difficulty in quickly matching two fingerprint images containing different number of unregistered minutiae points. The proposed matching algorithm that uses both minutiae (point) information and the texture (region) information is the solution in that direction. The algorithm uses a bank of Gabor filters to capture both local and global details in a fingerprint as a compact fixed length finger code. The finger print matching is achieved with the help of Euclidean distance between the two corresponding finger-codes and hence is extremely fast. Results obtained with the proposed scheme shows that a combination of minutiae and texture based score matching (local as well as global) information leads to a substantial improvement in the overall matching performance even at low resolutions.

Keywords: Fingerprint, Minutiae, Gabor Filter, Euclidian Distance

1.

I

NTRODUCTION

Biometrics, which refers to identifying an individual based on his or her physiological or behavioural characteristics, has the capability to reliably distinguish between two persons. Among all the biometrics (e.g. face, fingerprints, hand geometry, iris, retina, signature voiceprint, facial thermo diagram, hand vein, gait, ear, odor, keystroke dynamics, etc. [1,

2]), fingerprint based Criminal identificationis one of the most mature and proven technique and gained immense popularity due to the high level of uniqueness attributed to fingerprints.Recently, due to the advancement and availability of compact solid state sensors that can be easily embedded into a wide variety of devices have facilitated use of Automated

System for Criminal Identification based on the fingerprints found at the place of crime.

A fingerprint is the pattern of ridges and valleys on the surface of the finger [3]. The uniqueness of fingerprints can be determined by the overall pattern of ridges and valleys as well as the local ridge anomalies (a ridge bifurcation or ridge ending, called minutiae points). Although the fingerprint possesses the discriminatory information, designing a reliable automatic fingerprint-matching algorithm is very challenging as images of two different fingers may have the same global configuration. As fingerprint sensors are becoming smaller and cheaper [4], automatic identification based on fingerprints is becoming an attractive alternate / compliment to the traditional methods of identification. The critical factor on the widespread use of fingerprints is in satisfying performance (e.g. matching speed and accuracy) requirements of the emerging civilian identification applications. Some of these applications (e.g. fingerprint based smart cards) will also benefit from a compact representation of a fingerprint.

With the advent of live scan fingerprinting and availability of cheap fingerprint sensors, fingerprints are increasingly used in government and commercial applications for positive person identification [5, 6]. In the literature many schemes uses local landmarks i.e. minutiae based fingerprint matching systems or exclusively global information. The minutiae based techniques typically match the two minutiae sets from two fingerprints by first aligning the two sets and then counting the number of minutiae that match. A typical minutiae extraction technique performs the following sequential operations on the fingerprint image: (i)fingerprint image enhancement, (ii) binarization (segmentation into ridges and valleys), (iii) thinning, and (iv) minutiae detection. Several commercial [1] and academic [7-9] algorithms follow these sequential steps for minutiae detection. Number of researchers used the global pattern of ridges and furrows [10-12]. The simplest technique is to align the two fingerprint images and subtract the input from the template to see if the ridges correspond. However, such a simplistic approach suffers from many problems including the errors in estimation of alignment, non-linear deformation in fingerprint images, and noise. Combining both local and global features gives improved results in fingerprint verification [13-17]. So we have proposed an automated system for criminal identification based on hybrid features of the fingerprint image found at the crime scene.

2.

B LOCK D IAGRAM OF P ROPOSED S YSTEM FOR F INGER P RINTS

We describe a hybrid approach to identify the criminal based on fingerprint matching that combines a minutiae based representation of the fingerprint with a Gabor filter (texture based) representation for matching purposes. In the proposed algorithm when a query imprint is presented, the matching proceeds as follows: (i) The query and template minutiae features are matched to generate minutiae matching score and an affined transformation that aligns the query and

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013 Page 259

International Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & Management (IJAIEM)

Web Site: www.ijaiem.org Email: editor@ijaiem.org, editorijaiem@gmail.com

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013 ISSN 2319 - 4847 template fingerprints. (ii) Determine the reference point (core point) and tessellate the region of interest for the fingerprint image. (iii) Compute the average absolute deviation(AAD) from the mean of gray values in individual sectors in filtered images to define the feature vector or the finger code. (iv) The query and template finger codes are matched. (v)

The minutiae and finger code matching scores are combined to generate a single matching score (see Figure1).

Figure 1 Hybrid approach for criminal identification based on fingerprint matching

3.

C ORE P OINT D ETECTION

1.

Divide the input image, into non-overlapping blocks of size 8 8 .

2.

Compute the gradients x

( i , j ) and y

( i , j ) at each pixel ( i , j ) . Depending on the computational requirement, the gradient operator may vary from the simple Sobel operator to the more complex Marr-Hildreth operator.

3.

Estimate the local orientation of each block centered at pixel

( i , j )

using o

1

2 tan

1

V y

V x

( i ,

( i , j ) j )

(1) where,

V x

u i 4 j 4

i 4 v j 4

2 x

( u , v ) y

( u , v ) (2)

V y i , u i 4 j 4

i 4 v j 4

2 x

( u , v )

2 y

( u , v )

(3)

The value of o ( i , j ) is least square estimate of the local ridge orientation in the block centred at pixel

( i , j )

.

Mathematically, it represents the direction that is orthogonal to the dominant direction of the Fourier spectrum of the

8 8 window.

4.

Smooth the orientation field in a local neighbourhood. In order to perform smoothing (low pass filtering), the orientation image needs to be converted into a continuous vector field , which is defined as

1 x

cos

2 o ( i , j )

(4) and

1 y

sin

2 o ( i , j )

(5) where,

1 x

and

1 y

, are the x and y components of the vector field, respectively.

With the resulting vector field, the low pass filtering can be performed as,

x

w / 2 w /

2

W u w / 2 v w / 2

u , v

1 x

i wu , j wv (6) and

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013 Page 260

International Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & Management (IJAIEM)

Web Site: www.ijaiem.org Email: editor@ijaiem.org, editorijaiem@gmail.com

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013

y

w / 2 w /

2

W u w / 2 v w / 2

u , v

1 y

i wu , j wv (7)

ISSN 2319 - 4847 where, W (.) is a two dimensional low pass filter with unit integral and w w specifies the filter size.

Note that smoothing operation is performed at the block level. For our experimentation we have used a 5 5 mean filter.

The smoothed orientation field O at ( i , j ) is computed as,

O

1

2 tan

1

x y

( i ,

( i , j ) j )

(8)

5.

Compute the sine component of the smoothed orientation image O , using

E

i , j

sin

O ( i , j )

(9)

6.

Initialize

R

, a label image used to indicate the core point.

7.

For each pixel ( i , j ) in E , compute the difference in the pixel intensities of those pixels having different orientations in O .

8.

Find the maximum value in R and assign its co-ordinates to the core.

4.

R EGION OF INTEREST EXTRACTION

Let I

x , y

denote the gray level at pixel

x , y

in an region of interest is defined by a collection of sectors

M N fingerprint image and let

x c

, y c

denote the core point. The

S i

, where the i th

sector S i is computed in terms of parameters ( r , ) as follows:

S i

where,

b

x , y

i

T i

1

r

i 1

,

b

1

T i

2

, x N , 1 y M

(10)

T i

i div k

(11)

i

i mod k

2 k

(12) r

x x c

2

y y c

2

(13) tan

1

( y y c

)

( x x c

)

(14) b is the width of each band and k is the number of sectors considered in each band.

We use six concentric bands around the center point. Each band is 18-pixels wide ( b = 18), and segmented into eight sectors ( k = 8). The innermost band is not used for feature extraction because the sectors in the region near the center contain very few pixels. Thus, a total of 8 5 40 sectors

( S

0 through S

39

)

are defined.

5.

G ABOR FILTERS USED FOR FINGERPRINT FEATURE EXTRACTION

By applying properly tuned Gabor filters to a fingerprint image, the true ridge and furrow structures can be greatly accentuated. These accentuated ridges and furrow structures constitute an efficient representation of a fingerprint image.

The general form of a 2D Gabor filter is defined by (6). A fingerprint image is decomposed into eight component images corresponding eight different values of

k

= ( 0

0

, 22 .

5

0

, 45

0

, 67 .

5

0

, 90

0

, 112 .

5

0

, 135

0 and 157 .

5

0

) with respect to the x -axis.

6.

I MPLEMENTED A LGORITHM

In the proposed algorithm, the filter frequency f is set to the reciprocal of the inter-ridge distance since most local ridge structures of fingerprints come with well-defined local frequency and orientations. The average inter ridge distance is approximately 10 pixels in a 500 dpi fingerprint image. If f is too large, spurious ridges may be created in the filtered image, whereas if f

is too small, nearby ridges may be merged into one. The bandwidth of the Gabor filters is determined by

and x

y

. If the values of

x and

y

are too large, the filter is more robust to noise, but is more likely to smooth the image to the extent that the ridge and furrow details in the fingerprint are lost. On the other hand, if they are too small, the filter is not effective in removing noise. In the proposed algorithm, the values of

x and

y

were empirically determined and both were set to 4.0 and the filter frequency f is set to 0.1.

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013 Page 261

International Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & Management (IJAIEM)

Web Site: www.ijaiem.org Email: editor@ijaiem.org, editorijaiem@gmail.com

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013

Before decomposing the fingerprint image

I

x , y

, normalize the region of interest

ISSN 2319 - 4847

N i

x , y

in each sector separately to a constant mean and variance. Normalization is done to remove the effects of sensor noise and finger pressure differences. Let

I

x , y

denote the gray value at pixel

x , y

, M i

, and V i

, the estimated mean and variance of the sector S i

respectively and N i

x , y

, the normalized gray-level value at pixel

x , y

. For all the pixels in sector S i

, the normalized image is

N i

x , y

M

0

M

0

V

0

I ( x , y ) M i

2

V i

V

0

I ( x , y ) M i

2

V i

,

, if I ( x , y ) M i (15) otherwise , where

M

0

V

are the desired mean and variance values, respectively.

Normalization is a pixel-wise operation that doesn’t change the clarity of the ridge and furrow structures. If normalization is done on the entire image, then it cannot compensate for the intensity variations in the different parts of the finger due to finger pressure differences. Normalization of each sector separately alleviates this problem. In the proposed algorithm, both M

0

V to a value were set to 100.

After setting all the parameters of the Gabor filters, the even Gabor feature, at sampling point

( X , Y )

can be calculated using,

G

X , Y , k

, f , x

, y

M 1 N 1

x 0 y 0

N i

X x , Y y

g

x , y , f , k

, x

, y

(16) where N i

denotes a sector of normalized fingerprint image

I

x , y

of size M N , having 256 gray-levels.

k

Figure 2 (a)-(h) Gabor features of fingerprint image for

( 0

0

, 22 .

5

0

, 45

0

, 67 .

5

0

, 90

0

, 112 .

5

0

, 135

0 and 157 .

5

0

)

Figure 3 (a) Original image (b) Tessellated image (c) Reconstructed image using four Gabor filters (d) Reconstructed image using eight Gabor filters

The magnitude Gabor features at the sample point and those of its neighbouring points within three pixels are similar, while the others are not. This is because the magnitude Gabor feature has the shift-invariant property. A fingerprint image I

x , y

is thus normalized and convolved with each of the eight Gabor filters to produce eight component images.

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013 Page 262

International Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & Management (IJAIEM)

Web Site: www.ijaiem.org Email: editor@ijaiem.org, editorijaiem@gmail.com

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013 ISSN 2319 - 4847

Convolution with an parallel to the

0 oriented filter accentuates ridges parallel to the x -axis, and it smoothes ridges that are not x -axis. Filters tuned to other directions work in a similar way. According to the experimental results, the eight component images capture most of the ridge directionality information present in a fingerprint image (see Figure 2) and thus form a valid representation. It is illustrated by reconstructing a fingerprint image by adding together all the eight filtered images. The reconstructed image is similar to the original image but the ridges have been enhanced. Filtered and reconstructed images from four and eight filters for the fingerprint are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 4 (a) Original image (b) Tessellated image (c) Reconstructed image using four Gabor filters (d) Reconstructed image using eight Gabor filters.

6.1 Minutiae Extraction

Minutiae represent local ridge details. Ridge endings and ridge bifurcation are the two popular minutiae used for fingerprint matching applications. A ridge bifurcation is that point on an image where the ridge branches out into two and ridge ending is the open end of the ridge. These features are unique for every other fingerprint and are used for fingerprint recognition. A template image is created for all the detected ridge bifurcations and ridge endings in an image after false rejection as shown in Figure 5. The minutiae matching score is a measure of similarity of the minutiae sets of the query and template images. The similarity score is normalized in the [0,100] range.

(a) (b)

Figure 5 Minutiae set (a) queryimageand (b) template image

6.2 Finger code generation

To generate the Gabor filter-based finger code from the fingerprint image following steps are performed sequentially as:

Step 1: Find the core point of each fingerprint image.

Step 2: Tessellate the region of interest around the reference point into 40 sectors and sample the fingerprint image by set of Gabor filters to give N i k

x , y

, the filtered sectors of image in

k

directions.

Step 3: Now, i

1 , 2 , 3 , ......., 40

and

k

( 0

0

, 22 .

5

0

, 45

0

, 67 the mean defined as

.

5

0

, 90

0

, 112 .

5

0

, 135

0 and 157 .

5

0

) the feature values are the average absolute deviation from

F i

1

n i

n i

N i

( x , y ) P i

(17) where, n

, is the number of pixels in the sector i

S i

,

P i is the mean of pixel values in the sector S i

.

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013 Page 263

International Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & Management (IJAIEM)

Web Site: www.ijaiem.org Email: editor@ijaiem.org, editorijaiem@gmail.com

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013 ISSN 2319 - 4847

Thus, the average absolute deviation of each sector of the eight filtered images defines the components (320) of the finger code ( 8 5 8 ) . The query and template finger codes are then matched and the matching score is found. The minutiae and finger code matching scores are then combined to generate a single matching score.

7.

E XPERIMENTAL R ESULTS

Although the fingerprint databases of NIST, MSU, and FBI are sampled at 500 dpi, the fingerprint images can be recognized at 200 dpi by the human eye. The recognition of low quality images is efficient and practicable for a smallscale fingerprint recognition system. In the proposed system we have used a inked fingerprint image from the person (two images) and captured the digital format with a scanner at 200dpi and 256 gray-level resolutions. The minutiae and finger code is stored in the database as a template image. The minutiae features are unique for every other fingerprint and are used for fingerprint recognition.

Figure 6 (a)-(h) Finger codes for k

( 0

0

, 22 .

5

0

, 45

0

, 67 .

5

0

, 90

0

, 112 .

5

0

, 135

0 and 157 .

5

0

) (i) original image.

Figure 7 (a)-(h) Finger codes for k

( 0

0

, 22 .

5

0

, 45

0

, 67 .

5

0

, 90

0

, 112 .

5

0

, 135

0 and 157 .

5

0

) (i) original image.

Figure 6 and Figure 7 shows finger codes of two fingerprints belonging to different persons. From theseFigures we find that the finger codes of different persons do not match. This reveals that by using both the minutiae and the finger codes generated provides more security when it is used for criminal identification using fingerprints found at the location of crime. The fingerprint matching is based on the Euclidean distance between the two corresponding finger codes and hence is extremely fast.

Another experiment was performed to find the Euclidian distance between the test image and rest images of the same group. Table 1 shows the test results for 10 fingerprint images with its own individual set of 8-distracted images. This distraction was carried out with respect to brightness, contrast, partial cut of images, blurriness, etc. The implemented system results tabulated shows that if Euclidian distance is equal to zero then the perfect match has been found else not.

The test data shows that the Euclidian distance and its mean plays a vital role in identifying any given input image

(latent) with its corresponding stored template images (reference print). The implemented system outperforms on the whole database.

Table 1 Computation of Euclidian distance and Mean using the proposed algorithm

Serial No Image ID Euclidian Distance Mean of Euclidean Distance

1 101_1 0 (5570.8424 /8) = 696.3553

101_2

101_3

1322.2815

904.1864

101_4

101_5

840.7033

963.627

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013 Page 264

International Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & Management (IJAIEM)

Web Site: www.ijaiem.org Email: editor@ijaiem.org, editorijaiem@gmail.com

ISSN 2319 - 4847 Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013

101_6 522.3945

3

2

102_6

102_7

102_8

103_1

103_2

103_3

103_4

101_7

101_8

102_1

102_2

102_3

102_4

102_5

462.6671

554.9826

859.8459

1118.2438

941.0052

914.3823

939.1802

799.4998

756.8328

598.1988

1114.7228

768.2789

879.9089

1142.6031

(6927.1888 /8) =865.8986

(6358.405 /8) =794.800625

4

103_5

103_6

750.9579

705.0551

Serial No Image ID Euclidian Distance Mean of Euclidean Distance

103_7

103_8

104_1

445.9306

550.9477

741.2131 (4261.459 /8) =532.682375

104_2

104_3

104_4

104_5

104_6

104_7

104_8

578.8144

692.6348

584.2756

454.4189

392.6432

361.272

456.187

5 105_1

105_2

105_3

105_4

105_5

105_6

105_7

105_8

6 106_1

106_2

106_3

106_4

106_5

796.7528

841.3898

809.0306

957.4854

685.9827

756.334

528.4521

551.6303

652.761

708.5278

918.1781

731.8565

647.9269

(5927.0577 /8) =740.8822125

(5701.8574 /8) =712.732175

Serial No Image ID Euclidian Distance Mean of Euclidean Distance

106_6 611.8686

106_7 835.2303

106_8

7 107_1

107_2

107_3

595.5082

675.2977

654.7358

899.821

( 5999.043 /8) =749.880375

107_4 910.4479

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013 Page 265

International Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & Management (IJAIEM)

Web Site: www.ijaiem.org Email: editor@ijaiem.org, editorijaiem@gmail.com

ISSN 2319 - 4847 Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013

107_5 577.1496

107_6

107_7

107_8

8 108_1

108_2

108_3

108_4

108_5

108_6

108_7

108_8

9 109_1

109_2

109_3

902.5137

740.1758

638.9015

645.7223

509.1288

888.2192

496.0903

597.2147

659.3944

419.7498

630.9985

794.6275

754.6599

877.7669

(4846.51872 /8) =605.81484

(5317.2688 /8) =664.6586

109_4 914.9374

Serial No Image ID Euclidian Distance Mean of Euclidean Distance

109_5 565.109

109_6

109_7

109_8

10 110_1

110_2

110_3

475.1324

552.8026

382.2331

932.6882

740.8111

755.3441

( 5546.1557/8) =693.2694625

110_4

110_5

110_6

110_7

655.5515

502.4248

592.0504

719.5817

Figure 8 Enrollment of the fingerprint image from the subject.

The Snapshots of the GUI for various imprints are provided below. Accept the fingerprint image from the subject using a fingerprint sensor.Then enrolment of the fingerprint image from the subject in the form of feature vector is carried out as shown in Figure 8. Matching the query fingerprint image found at the crime scene with the fingerprint images available in the database is then carried out as shown in Figure 9.

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013 Page 266

International Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & Management (IJAIEM)

Web Site: www.ijaiem.org Email: editor@ijaiem.org, editorijaiem@gmail.com

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013 ISSN 2319 - 4847

Figure 9 Matchingthe query fingerprint image found at the crime scene with the fingerprint images available in the database.

8.

C

ONCLUSION

The proposed matching algorithm that uses both minutiae (point) information and the texture (region) information is more accurate. Results obtained on the fingerprint captured in digital format with a scanner at 200 dpi and 256 gray level resolutions shows that a combination of minutiae based score matching and texture based (local as well as global) information leads to a substantial improvement in the overall matching performance. The filter frequency f and the values of

x and

y that determine the bandwidth of the Gabor filter should be selected properly. If f

is too large, spurious ridges may be created in the filtered image, whereas if f is too small, nearby ridges may be merged into one.

Similarly, if the values of x and

y

are too large, the filter is more robust to noise, but is more likely to smooth the image to the extent that the ridge and furrow details in the fingerprint are lost. On the other hand, if they are too small, the filter is not effective in removing noise. The fingerprint matching using Euclidean distance between the query and the template image is extremely fast. This reveals that by setting the parameters to appropriate values, the method is more efficient and suitable than the conventional methods as an automated system for criminal identification based on fingerprints found at the crime scene.Also, the Euclidian distance and its mean play a vital role in identifying any given input image with its corresponding stored template images.

References

[1] S. Pankanti, R.M. Bolle, A. Jain, “Biometrics: the future of identification,” IEEE Comput. 33 (2) (2000) 46–49.

[2] A. Jain, R. Bolle, S. Pankanti (Eds.), “Biometrics: Personal Identification in Networked Society,” Kluwer Academic,

Dordrecht, 1999.

[3] D. Maio and D. Maltoni, “Direct Gray-Scale Minutiae Detection in Fingerprints,” IEEE Trans. PAMI, Vol 19, No 1, pp 27- 40, 1997.

[4] G. T. Candela, P. J. Grother, C. I. Watson, R. A. Wilkinson, and C. L. Wilson, “PCASYS: A Pattern-Level

Classification Automation System for Fingerprints,” NIST Tech. Report NISTIR 5647, August 1995.

[5] H. C. Lee, and R. E. Gaensslen, “Advances in Fingerprint Technology,” Elsevier, New York , 1991.

[6] S. Prabhakar, and A. K. Jain, “Fingerprint Classification and Matching,” A PhD thesis Submitted to Michigan State

University, 2001.

[7] N. Ratha, K. Karu, S. Chen, and A. K. Jain, “A Real-Time Matching System for Large Fingerprint Databases,” IEEE

Trans. Pattern Anal.and Machine Intell.

, Vol. 18, No. 8, pp. 799-813, 1996.

[8] A. K. Jain, L. Hong, S. Pankanti, and Ruud Bolle, “An Identity Authentication System Using Fingerprints,”

Proceedings of the IEEE , Vol. 85, No. 9, pp. 1365-1388, 1997.

[9] X. Jaing, W. Y. Yau, “Fingerprint Minutiae Matching based on the Local and Global Structures,” Proc. 15th

International Confererence on Pattern Recognition , Vol. 2, pp. 10421045, Barcelona, Spain, September 2000.

[10] A. K. Jain, L. Hong, and R. Bolle, “On-line Fingerprint Verification,” IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. and Machine

Intell.

, Vol. 19, No. 4, pp. 302-314, 1997.

[11] A. K. Jain, S. Prabhakar, and L. Hong, “A Multichannel Approach to Fingerprint Classification”, IEEE Trans.

Pattern Anal.and Machine Intell.

, Vol. 21, No. 4, pp. 348-359, 1999.

[12] A. K. Jain, S Prabhakar, L Hong, and S Pankanti, “Filterbank-based Fingerprint Matching,” IEEE Trans. Image

Proc.

Vol 9, No 5, pp 846-859, 2000.

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013 Page 267

International Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & Management (IJAIEM)

Web Site: www.ijaiem.org Email: editor@ijaiem.org, editorijaiem@gmail.com

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013 ISSN 2319 - 4847

[13] A. K. Jain, A. Ross, and S. Prabhakar, “Fingerprint Matching Using Minutiae and Texture Features”, in proc. of the

Int. Conf. on Image Processing (ICIP) , Greece, pp 282-285, Oct. 2001.

[14] A. Ross, A. K. Jain, and J. Reisman, “A hybrid Fingerprint Matcher”, in proc. of the Int.Conf. on Pattern

Recognition (ICPR) , Quebec City, Aug.2002.

[15] A. K. Jain, S. Prabhakar, and S. Chen, “Combining Multiple Matchers for a High Security Fingerprint Verification

System”, Pattern Recognition Letters, Vol 20, No. 11-13, pp. 1371-1379, Nov.1999.

[16] A. K. Jain, L. Hong, S. Pankanti, and R. Bolle, “An Identity Authentication System using Fingerprints,” Proc. of the

IEEE, Vol. 85, No 9.

[17] Pradeep M. Patil, Shekhar R Suralkar, and Faiyaz B Shaikh, “System authentication using hybrid features of fingerprint,” ICGST International Journal on Graphics, Vision and Image Processing (GVIP), Issue 1, Vol. 6, July

2006, pp. 43-50.

Author:

M.P. Deshmukh :- He recieved M.E. from MNREC, Allahabad and presently persuing his PhD from North

Maharashtra University, Jalgaon (M.S.). He has 24 years of teachingexperience

Prof (Dr) P.M. Patil:-l He is having 25 years of experience and at present Director & Principal RMD, SIT,

Warje, Pune. He has several publications in national & International journals and number of research students are persuing PhD under his guidance.

Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2013 Page 268