AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Dennis Albert Neilson Master of Forestry

advertisement

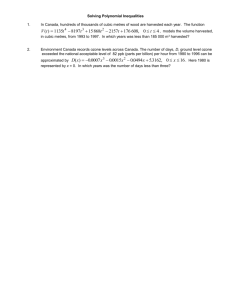

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Dennis Albert Neilson Forest Enqineering in Title: for the degree of presented on Master of Forestry December 9, 1977 The Production Potential of the Iqland-Jones Trailer Alp Yarder in Thinninq Younq Growth Northwest Conifers: A Case Study Abstract Approved: Dean Edward Aulerich Results of a recent production study indicate that a four man crew thinning young growth Douglas-fir [Pseudotsuga mensiezii (Mirb.) Franco] with an Iglarid-Jones Trailer Alp can produce 1360 to 1460 cubic feet (38 to 41 cubic metres; 8160 to 8750 bd. ft.,) per eight hour day on slopes of 10 to 50 percent with average slooe distances of 150 to 300 feet (46 to 91 metres) and average lateral yarding distances of 30 to 50 feet (10 to 15 metres). The stand studied was thinned from 226 stems per acre (558 stems per hectare) to 130 stems per acre (321 stems per hectare). The average tree size removed was 19.4 cubic feet (0.55 cubic metres) and the average log size yarded was 12.9 cubic feet (0.36 cubic metres). A standing skyline system was used with a haulback line attached to hold the carriage in position during lateral yarding. The cost of a four man crew felling, bucking, and yarding this material with an average slope distance of 250 feet (76 metres) and an average lateral yarding distance of 35 feet (11 metres) is estimated at $36.63 per cunit ($12.93 per cubic metre; $61 .04 per Mbf.). A three man crew operating under the same conditions would produce only 1160 cubic feet (33 cubic metres; 6950 bd. ft.) per day but the unit cost of production would be lower at $35.30 per cunit ($12.46 per cubic metre; $58.83 per Mbf.). During the study, operating delays accounted for 26 percent 0f total study time and skyline road changes accounted for 10 percent of total study time. The use of intermediate supports can successfully extend yarding distance on unfavorable slopes and can facilitate efficient decking if placed within 100 feet (30 metres) of the landing. The Production Potential of the Igland-Jones Trailer Alp Yarder in Thinning Young Growth Northwest Conifers: A Case Study by Dennis Albert Neilson A PAPER submitted to Oregon State Univerty in partial fulfillnient o.f the requirements for the degree of Master of Forestry Completed December 9, 1977 Commencement June, 1978 Approved: Professor of Forest Engineering Head of the Department of Forest Engineering Dean of the Graduate School Date thesis is presented Typed by C. Joy Martin for December 9, 1977 Dennis Albert Neilson TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 OBJECTIVES OF STUDY 3 OPERATING CONDITIONS 4 Area and Stand Description :4 Stand Assessment Data - 4 Selection for Thinning 10 Yarding System 11 STUDY METHOD - 19 Elements of Yarding Cycle Variables of Yarding Cycle -- 19 -- 21 Delays 22 Road Changes - - Rigging Intermediate Supports DATA ANALYSIS - 2. 25 26 Sumary of Yarding Cycle - 26 Regression Analysis 28 Delays - 37 Road Changes 41 Intermediate Supports 43 Potential Producticn 46 Casts 52 DISCUSSION OF RESULTS Productivity Sensitivity 53 53 of Production 55 Table of Contents (continued) Lateral Yarding 55 Intermediate Supports 55 Crew Size 61 Stand Damage 63 FUTURE STUDIES 65 CONCLUSION 66 BIBLIOGRAPHY 68 APPENDICES 69 Appendix 1 70 Appendix Z 71 Appendix 3 72 Appendix 3a 73 Appendix 4 Appendix 5 75 Appendix 76 6 Appendix 7 - 77 Appendix 8 78 Appendix 9 79 Appendix 10 8 Appendix 11 82 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1 Blodgett Tract, Columbia County 5 2 Trailer Alp Study Area 6 3 Diameter distribution pre-and post-thinning 12 4 Distribution of log lengths yarded 12 5 Igland-Jones Trailer Alp 14 6 Igland-Jones Trailer Alp Trailer 15 7 Single span carriage 16 8 Multispari carriage 16 9 Alp .jack and support line 18 10 Example of a maintained and neglected deck 36 11 Distribution of turn volumes-thinning 40 12 Distribution of turn volumes-clearfelling 40 13 Line tightener 44 14 Swedish climbing ladder - Virginia study 47 15 Production per hour as a function of lateral and slope distance (standard units) 50 15a Production per hour as a function of lateral and slope distances (metric units) 61 16 Production per hour as a function of slope 56 distance and volume per piece (standard units) 16a Production per hour as a function of slope distance and volume per piece (metric units) 57 17 Production per hour as a function of slope distance and percent delays (standard units) 58 17a Production per hour as a function of slope distance and percent delays (metric units) 59 18 Example of ringbark damage 64 LIST OF TABLES Table Page 1 Pre-Thinning Assessment Piot Data 8 2 Post-Thinning Assessment Plot Data 9 3 Stand Characteristics Pre- and Post- Thinning 10 4 Trailer Alp Drum Specifications 13 5 Summary of Yarding Cycle Times 26 6 Summary of Production Variables 27 7 Delays 38 8 Road Changes 42 9 Sumary of Time Usage 43 10 Rig Support Times 45 U Support Tree Limbing Times 45 12 Dafly Operating Costs 52 LIST OF APPENDICES Appendix Page Profiles of Skyline Roads Studied 70 2 Hewlett Packard 9830 Used to Calculate Estimated Producti on per Hour TI 3 Line Pulling Forces - Standard Units 72 3a Line Pulling Farces - Metric Units 73 4 Daily Cost - Trailer Alp Yarder 74 5 Dafly Cost - John Deere 2640 Tractor 75 6 Daily Cost - Crew Transportation 76 7 Daily Cost - Chainsaws 77 8 Dafly Cost - Radio 78 9 Determination of Production and Cost Data for Three Man Logging Crew 79 10 Net Production Rate for Four Man Crew 81 11 Falling and Bucking Productivity 82 1 THE PRODUCTION POTENTIAL OF THE IGLAND-JONES TRAILER ALP YARDER IN THINNING YOUNG GROWTH NORTHWEST CONIFERS: A CASE STUDY INTRODUCTION Approximately 3.3 million acres (1.3 million hectares) of commercial forest land in the Douglas-fir sub-region of Oregon and Washington conist of stands between 20 and 70 years old, (Aulerich, 1975) and are considered young growth stands. This amounts to about 24 percent of the total area in commercial forest. Both the acreage and the percentage of commercial forest in this age group will increase significantly within the next. decade as old and second growth forests are depleted or 'locked up" by conservation legislation. According to Aulerich (1975) most of the stands 20 to 70 years old consist of trees under 20 inches (51 cm) dbh. or log volumes averaging less than 25 cubic feet (0.7 metres). Historically, the limited logging of this small piece size material has been done with yarders which were designed to yard old growth and second growth forests. The high capital and operating costs of these machines, the difficulty of setting up and yarding with them in small wood (especially thinnings) and the adequata supply of larger material has discouraged the utilization of many of the smallwood stands. This situation is changing rapidly, however. The Forest Engineering Department of Oregon Stata University, anticipating the need to improve harvesting operations in small timber, 2 'embarked on a research project in 1972 to examine current harvesting practices and develop and, test more efficient and economic techniques to utilize small stands. One result of this project has been the acquisition of an IglandJones Trailer Alp yarder to be tested in smallwood stands under Northwestern conditions. The purchase and research on this machine has been funded on a cooperative basis by a number of private companies. The testing of the machine is the responsibility of the Forest Engineering Department of Oregon State University. The Departrnent has contracted the operation of the yarder to a small, independent logging organization. During the summer of 1977, the Igland-Jones Trailer Alp was used to thin a stand of Douglas-fir in the Blodgett Tract Forest in Northwest Oregon (Figure 1). During the tests, measurements were made of the various facets of the operation and the data analyzed to determine the production potential of the machine. A description of the study and the presentation of the results forms the basis for this paper. I, 3 OBJECTIVES The objectives of the study were: To evaluate the perforinance of the Igland-3ones Trailer Alp yarding smallwood thinnings with external yarding distances of less than 1000 feet (300 metres). To investigate the use of intermediate supports as an aid to extending the yarding distance on unfavorable slopes. To develop production equations for the major elements of the yarding cycle and ue these to predict the production potential of the machine over a range of conditions. 4 OPERATING CONDITIONS Area and Stand Description The area chosen for the study was a stand of 35 to 40 year old Douglas-fir in the University owned Blodget Tract Forest in Columbia County, Oregon; 17N, R514, WM (Figure 1). The stand sloped away from a logging spur road at slopes ranging from 10 tQ 70 percent. Along much of the stand, a prominent convex break in slope occurred 200 to 300 feet (60 to 90 iTietres) from the road which would have made single span yarding difficult for four of the seven skyline roads studies. Western hemlock Tsuga heterophylla (Raf.) Sarg.] stems were dispersed throughout the western section of the stand and a pocket of red alder [Alnus rubra (Bong)] was established within the stand along an intermittent water course (Figure 2). The alder was clearfelled and yarded during the study period, but the data analysis and discussion presented in this paper is restricted to the thinning operation only, unless otherwise stated. Stand Assessment Data Pre-Thinning Assessment A total of eight 0.2 acre (0.08 hectare) circular plots were randomly selected and measured prior to logging. measured included species and diameter. Parameters A random selection of 23 trees through the existing height range were measured for height and 5 . 'S \ P.ckRoas irP.as 1d P.i1z Graas Ses Tyce U.te -. ip.,. Trailer Alp Study Area (section 30) ,, Figure 1. Columbia County T7M, R5W, WM 80 Foot Contour Interval mile (3.8 cm = 1 Km) Scale: 2.4" = Blodget Tract. 1 Leqend -I--I i-i--h 6. Old Railway Grade 1nterrneiate Support Skyline Road Road Ridge - Draw Not Logged During Study Period. " Pocket of red alder Road to Mist, Oregon Prepared by: D.E. AuleriCh. .June,1977. Figure 2. Trailer Alp Study Area SCALE: 12OO' (1 cm = 24 m) S 7 diameter, and this information was used to calculate a tariff number (Little, 1972). Individual tree volumes [to a six inch (15 cm) top] were obtained from Douglas-fir tree volume tables (Turnbull et al., 1972). For the purpose of this assessment, western hemlock stems were identified separat&y from Douglas-fir, but individual tree volumes were selected from tree volume tables of the latter species using the single derived tarif-F number. Post-Thi nni ng Assessment Eight 0.2. acre (0.08 hectare) circular plots were randomly se1ectd after the thinning operation was complete. Individual tree volumes were selected using the same tariff number derived from the pre-thinning assessment. 8 Table 1. All Plots 0.2 Acre Plot No. No. of Stems 1 Pre-Thinning Assessment Plot Data (0.08 hectare) Tariff Number = 29 Volume to 6" (15 cm) Volume per Tree (cu.ft) (cu.m) 54 990.4 27.98 18.3 0.52 2 45 997.8 27.62 al.7 0.61 3 47 1252.0 35.37 26.6 0.75 4 4g 1232.5 34.82 25.1 0.71 5 38 1042.7 29.45 27.4 0.77 50 957.2 27.04 lg.1. 0.54 7 34 796.6 22.50 23.4 0.66 8 46 851.8 24.06 18.5 0.52 45 1012.6 28.60 22.5 0.64 1.30 (5.8%) 0.04 Mean (cu.ft) (cu.m) SE. of 2.17 Mean (4.8%) 57.29 (5.6%) 1.62 9 Table 2. AU P1ot PTht No. Post-Thinning A.seszment Plat Data 0.2 Acre (0.08 hectare) Na. Stems Tariff Number = 29 Volume to 6" (15 cm.) (cu.ft) (cu.m) Volume per Tree (cu.ft) (cu.m) 1 28 723.3 20.43 25.8 0.73 2 32 667.7 18.86 20.9 0.59 3 21 703.5 19.87 33.5 0.95 4 28 648.8 19.34 24.5 0.69 6 30 732.1 20.68 24.4 0.69 6 26 555J 15.68 2L3 0.60 7 26 481.1 13.59 18.5 0.52 8 17 589.0 16.64 34.6 0.98 Mean 26 642.0 18.19 25.4 0.72 1.72 32.10 0.9 2.06 (8.1%) 0.58 S,E. of Mean (6.6%) (5.0%) 10 Table 3. Stand Characteristics: Pre and Post Thinning Pre-Thinning Number of stems per acre per hectare Post-Thinning 226 558 130 Volume (cu.ft. per acre) (cu.m per hectare) 5060 354 3210 225 Average D.B.H. (inches) 14.1 36 14.7 190.5 43.7 118.6 27.2 (cm) Average basal area (sq.ft. per acre) (sg.m. per hectare) Height (feet) (metres) 321 37 85 26 The thinning operation removed 42 percent of the fir-hemlock stems and 37 percent of their volume. Selection for Thinning Tree selection for thinning was performed by the fallers. They were instructed to thin approximately 50 percent of the existing stems but to use their judgnent with regard to spacing, tree form, and size. Many of the well-formed trees in the stand were removed because of bear damage to the cambial layer. The fallers were instructed to cut peeler length logs and utilize each tree to a five inch (13 cm) top if possible, although many final bucking cuts were made closer to six inches (15 cm). 11 (175) 7 (75)3 0 (50)2 E 0 (inches) (cm) Figure 3. 7 9 11 18 23 28 13 33 Diametar distribution: 15 38 17 43 19 21 23+ 48 53 5B Pre and Post-Thinning 1 00 75 - 50 25 - 0 1O'O' 3.05m 1718U 27b01t 348" 4210" 5.39ni 8.23ni 1O.57m 13.06m - Figure 4. Log Lengths Distribution of log lengths yarded 12 Figure 3 details the diameter distribution pre- and postthinning and Figure 4 illustrates the percentage of each log length cut during the study. Yarding System The Igland-Jones Trailer Alp yarder is of Scottish-Norwegian design. It consists of a single-.axled trailer with skyline, mainline, haulback and utility drums, two winches, a tower and carriage (Lisland, 1975). The machine studied was transported between skyline roads and powered during yarding by a John Deer 2640, 70 h.p. farm tractor (Figure 5). Power for the winches is transmitted to the trailer by a transmission shaft driven from the tractor and by chain drive to the winches. An Igland 5000 compact double drum winch is. mounted on the front of the trailer (A), ropes. which is used for strawline and other spare On one side is a chain drive for powering the skyline drum. Behind this winch, is the skyline drum (B). This is split into two parts, one for storing the skyline and one for tightening it (Figure 6). The skyline brake is sufficient to keep full tension on the skyline without extra anchoring of the cable. Unloaded skyline tensions of up to 12,000 lbs. (5450 Kg) were measured during the study. At the back of the trailer, an Igland special 3000/2H winch is mounted (C). This winch drives the mainline and haulback drums. 13 Clutches and brakes are mechanical, but hydraulically operated. controls are mounted on a movable arm CD). The Hydraulic guages are installed to measure the pressure on the clutches and brake system. Table 4. Drum Type Trailer Alp Drum Specifications Rope Capacity (ft) (metres) Diameter (ins) Line Speed (cm) (ft/mm) (rn/mm) Skyline 2600 800 6/8 1.6 400-1000 l20300 Mainline 1800 650 3/8 1.0 400-1000 120-300 Haulback 1800 550 3/8 1.0 400-1000 120-300 The tower is 23.7 feet (7.21 metres) high. The skyline, mainline, and haulback lines pass through blocks on swivel fairleads at the top of the tower. Three guylines ar attached to the top of the tower and anchored so as to stabilize the machine during yarding. A standing skyline configuration was used during the study. A haulback line was used to help move the carriage from the landing to the chokeretter, and to hold the carriage in place during lateral inhaul. Two different carriages were operated during the study period: a simple carriage for single span logging (Figure 7) and a second carriage (Figure 8) designed to pass over a support jack was used for yarding on multispan roads. .4 ) 3 - I.UIrn Figure 5. /9/ ft g-._ - ---- - 2.13" -- -- -_-.4- - - Igland-Jones Trailer Alp -- -. 'ii .. - -! control Levers I ,, Figure 6 Igland-Jones Trailer Alp Trailer 16 i Figure 7. Single span carriage Ewt = 35 lbs. (16 Kg.)] 41 *: k Figure 8. Multispan carriage Ewt = 80 lbs. (36 Kg.)] 17 A total of seven skyline roadz were studied, four o-F which used at leazt one intermediate support. Each support consisted of an Alp Jack (42 lbs., 19 Kg.) hung from a block which in turn was suspended on a one-ialf inch support line (Figure 9). This line pazzed through blockz strapped on two support trees situated perpendicular or near perpendicular to the skyline road and was tied down to stumps or trees on either side of the support treez. A single chokersetter operated for 75 percent of the turns observed. He pulled line nianually for lateral yarding. A second chokersetter aszisted with line pulling and chokersetting at slope distances greater than 500 feet (150 nietres) on slopes of 10 to 40 percnt, and greater than 300 to 400 feet (90 to 120 nietres) on slopes lesz than 10 percent. acted as a chaser. A third crew niember operated the yarder and also Logs were cold decked to be loaded out at a later date by a self-loading truck. 18 - J Figure 9. Alp jack and support line 19 STUDY METHOD Yarding cycle element times (in centiminutes) were taken with a stopwatch. A wristwatch was used to time the elements of road changes and delays lasting longer than one hour. One tinier observed the woods operations, and, when available, a second timer observed the landing operation. Elements of Yarding Cycle The following elements of the yarding cycle were identified and measured. Outhaul empty - began when the operator was ready to move the carriage out to the chokersetter and ended when the chokersetter touched the chokers. Sort rigging (chokersetter) - began at the end of the outhaul empty element and ended when the chokeretter was ready to move latera.11y. This element 'involved untangling the chokr if necessary and occurred on 32 percent of the turns observed. Lateral out - began at the end of the sort rigging element and ended when the chokersetter was ready to hook a turn. Hook - began at the end of lateral out and ended when the chokersetter had completed hooking and signaled the yarder operator to begin the 'inhaul process. Lateral in - beQan at the end of the hook element and ended when the turn was pulled up to the carriage and began to move up the skyline corridor. a 20 Reset - an element which occurred when a turn became hung up and one or more logs had to be rechokered. It began when the chokersetter signaled for the turn to be stopped and ended when the turn began moving again, after being reset. This element occurred on 23 percent of the turns studied. Inhaul - began at the end of the lateral in element and ended when the turn had reached the position on the deck where it could be directly unhooked. Unhook began at the end of the inhaul element and included the operator walking into the choker(s), unhooking and walking back to the machine to begin the outhaul element. Position an element which began at the end of inhaul and It ended when the operator was ready to move in to unhook. occurred when a turn had to be positioned on the deck before it could be unhooked and was observed on 16 percent of the turns studied. Sort rigging (operator) an element which was isolated from the unhook sequence if the operator had to untangle the rigging before sending the carriage out to the woods. This element occurred on seven percent of the turns observed. Sort deck - an element which involved the operator flatten- ing down the deck or moving logs so that further logs could be landed safely. turns observed. This element occurred on 21 percent of the 21 Variables of the Yarding Cycle These variables included: Slope distance. The slope distance from the yarder to the tail tree was measured with a tape before yarding commenced and marked every 50 feet (15 metres) with paint. The lateral yarding distance was normally Lateral distance. paced to the nearest 10 feet (3 metres) during yarding operations. However, this distance was measured with a tape if the position of the lateral corridor could be determined before yarding commenced. This distance was measured as the slope distance from the skyline corridor to the hook point. Volume. Each log was premeasured and tagged before yarding so individual piece volumes could be later identified. The large end and small end diameters (inside bark) and the length of each log were measured. Log volumes were calculated using the equati on: V = 0.001818 * L * (012 + 022 + 01 * 02) (Wood Handbook, 1974) where: V = L = D1= D2= volume in length in large end small end Skyline height. cubic feet feet diametar inside bark in inches diameter inside bark in inches The height of the skyline above the ground at the carriage was visually estimated. In addition, the number of chokers used, the number of chokersetters operating, the number of logs per turn and the number of intermediate suppor-t used were recorded by the observer in the woods. The 22 landing observer measured the deck height to the nearest foot using a premarked measuring stick. The average groundslope of each corridor in percent was calculated from data collected during the field survey of the skyline roads. Groundslope was chosen as a variable rather than chordslope as the skyline tends to more closely follow the ground than the chord when intermediate supports are used. Delays The cause of each delay was noted during the study but during the analysis eleven delay codes were identified, and each delay was placed into one of these codes. It was noted during the analysis that delay times could be separated into two distinct categories. These categories have been defined as operating delays and experimental delays. Operating delays were those considered to be part of the normal yarding operation. Experimental delays were those considered to be atypical o-F a normal operation. Examples include downtime caused by visitors, crew un-Familiarity with the equipment, and the experimental nature of the logging system. The latter delays have been excluded when calculating machine utilization and production potential. The breakdown of the delays into the above categories within delay codes is detailed in Table 7. The delay codes included: Prepare - this time was spent in personal and yarding preparation each day, and was the elapsed time between arriving 23 on the job and the commencement of yarding operations. Fell and buck - this involved felling and bucking trees hung up during falling, and also removing trees badly damaged during logging. Snag problems - the Trailer Alp did not have the power to drag logs through old snags which were scattered throughout the stand. Often snags had to be "rigging cut" to enable yarding to continue and this time was considered a snag problem delay. Ropes and Carriage - this time included splicing broken rope and replacing bolts and plates on the carriage. It also included the time spent respooling the mainline, which occasionally rapidly unwound from the drum and tangled. Supports - the time spent rehanging the skyline in the jack or ad,juting the height of the jack was considered support delay. Mechanical - any time spent repairing the yarder was considered mechanical delay. Deck problems - on one occasion, the deck became so cluttered that turns cüuld not be landed, and the operator was forced to pull a number of logs off the deck using the utility drum. This time was considered a deck problem delay. Personal - this included time taken by the operator and chokersetter. Radio - the downtime caused by the need to repair faulty transmitters, receivers, and aerial. Other - these delays included downtime caused by visits and waiting for a truck which loaded out during yarding on two 24 occasions. Unspecified - those delays which could not be identified by the observer. Road Changes The following elements in the road change sequence were identified and measured: Rigging in - this element began upon completion of yard and ended when all the rigging lines and carriage were at the yarder. Guylines in - this element began when one or more crew members moved towards the guyline stumps and ended when the guylines were ready for the machine to move. Move machine - this element began when the operator started to remove the transmission shaft from the tractor power take off unit and ended when the machine was in position at the new site and attached to the power source. Guylines out - this element started when the guylines were moved towards the new anchor stumps and ended when they were tightened. Rigging out - this element started when the first rigging line was moved and ended when all the lines, and carriage, were in position. Raise supports - this element included the time taken to place the skyline in the jack, raise the jack to the required height, and anchor the support line. It did not include the time to hang the clocks and support line because they were 25 prerigged. The variables measured during the road change cycle included the slope distance of the skyline road, the distance between skyline roads, the number of supports used and the crew size. Rigging Intermediate Supports Two rigup times for intermediate supports were measured and the results are presented in Table 10. During the study, most of the support trees were prelimbed before being rigged and two supports were prehung by the faller while yarding corrtinued. The elements of intermiediate support rigup identified included: Move in rigging - the time taken to carry the support rigging, jack, and climbing gear to the support trees. Hang rigging - the time taken to climb, limb, and hang support blocks in both support trees. Anchor support line - the time taken to anchor the support line to nearby trees or stumps. p 26 DATA ANALYSIS Summary 0f the Yarding Cycle The average element times for the thinning study are presented in Table 5, together with the maximum and minimum times recorded for each element. Table 6 presents similar values for the variables which influenced these times. Table 5. El ement. Summary of Yarding Cycle Times No. of Obs. Max. Time (mm) Mm. Avg. Time Time (rain) (mm) Percent Outhaul 549 2.5 0 0.70 15.6 Sort Rigging (chokersetter) 549 2.00 0 0.10 2.2 Lateral Out 549 2.27 0 0.42 9.4 Hook 549 6.30 0.65 14.5 Lateral In 549 4.29 0 0.42 9.4 Reset 549 6.98 0 0.35 7.8 Inhaul 549 2.38 0 0.69 15.4 Position, 549 2.22 0 0.12 2.7 Unhook 549 6.30 0.60 13.4 Sort Rigging (Operator) 549 2.00 0 0.07 1 .6 Deck 549 9.12 0 0.36 8.0 4.48 100.0 Total Turntime Without Delay 0.05 0.05 f 27 Table 6. Summary of Production Variables Average Value Variable Slope Distance (ft) (iii) Lateral Distance (ft) (rn) Skyline 1-leight (ft) (rn) Logs Per Cycle 650 0 224 200 0 68 140 0 41 42 0 12 48 6 17.5 15 2 6.3 1 1.62 4 Volume Per Cycle (cu.ft) (cu.rn) 60.0 2.1 1.69 0.06 21.0 0.59 2 1 1.25 Chokes per Cycle 2 1 1.68 Logs Preset per Cycle 1 0 0.14 Chokersetter per Cycle 28 Regression Ana]ysis Regression equations were generated which relate element times to one or more of the variables measured. The stepwise regression proce- dure was used with the SIPS statistical package program for the Control Data Corporation 3300 computer (OS-3 operating system) to test hypotheses, determine regression coefficients and coefficients of determination. The acceptance or rejection of variables in each regression was determined using a combination of required confidence interval of 95 percent and the marginal increase in the coefficient of determination value (R2) obtained by adding each new variable. If the addition of new variables to a regression did not improve the R2 value by more than one percent, even though they were significant at 95 percent, they have been rejected. In the regression equations that follow: SLPDST = slope distance in feet or metres SKYHT GRDSLP NOSUP = skyline height in feet or metres groundslope in percent = the number of intermediate supports LATDST = lateral distance in feet or metres NOCS = the number of chokersetters used NCLGS = the number of logs per turn VOL = volume in cubic feet or cubic metres PRST = the number of preset logs 29 1) Outhaul time (in minutes) H0: Outhaul = f(SLPDST, SKYHT, GRDSLP, NOSUP) Outhaul = 0.25T1 n = 549 + 0.00198 * SLPDST (standard units) Outhaul R2= 0.685 0.25T1 + 0.00649 * SLPDST (metric units) The addition of the other three variables increased the by only 1.5 percent and so the above equations are accepted. value Ground- slope is not a significant variable, probably because the operator held the mainline tight during outhaul and pulled the carriage out with the haulback line. By doing this, he did not take advantage of increasing groundslope returning the carriage more quickly. Sort Rigging (Chokersetter) (in minutes) Average time per turn = 0.10 minutes Standard deviation = 0.233 minutes Standard error of mean = 0.010 minutes n 549 Because of the random nature of this element, no significant regression equation could be generated. Lateral Out Time (in minutes) H0: Lateral Out = f(LTDST, LATDST2, SLPDST, SKYHT, NOCS, GRDSLP) Lateral Out = 0.116 + 0.00G260 * SLPDST n = 549 0.553 30 + 0.00756 * LATDST - 0.05067 * NOCS (standard units) Lateral Out = 0.1161 + 0.000853 * SLPDST + 0.0248 * LATDST - 0.05067 * NOCS (nietric units) Addition of the other three variables added less than 0.01 to the R2 value and so the above equations are accepted. The lateral distance was the most significant variable, as expected; but the slope distance was also a factor as it reflects the force required to pull line to any given lateral distance. Groundslope also affects the force required to pull line but it was not a significant variable in the equation. 4) Hook Time (in minutes) H0: Hook = f(NOLG, VOL, GRDSLP, NOCS, PRST) Hook = 0.4133 + 0.1653 * NOLGS n = 549 R2=0. 081 - 0.2121 * PRST (standard and metric units) Even with all five variables included, the R2 value increased by only 0.003. None of the above variables is significant at 96 percent. As 92 percent of the variation in hooktime was caused by factors other than the above variables, little reliance can be placed on it and an average hooktime is presented here. 31 Average time per turn = 0.65 minutes Standard deviation = 0.521 minutes Standard error of mean = 0.0197 minutes 5) H : Lateral In Time (in minutes) Lateral In = .0 Lateral In f(LATDST, LATDST2, VOL. NOLGS, SKYHT, LATDST * NOLOGS) = 0.1080 n 0.00987 * - 0.03501 * LADST = 549 R2= 0.253 LATDST2 1000 (standard unitz) Lateral In = 0.1080 + 0.032 - * 0.3765 * LATDST L.ATDST2 1000 (metric unitz) Addition of the four other variables increased the R2 value by less than 0.01 and so the above equations are accepted. As expected, the lateral distance was the dominant influence in the time taken to yard logs to the skyline corridor. The relatively low value obtained may be attributed to the variation in number and effectiveness of obstructions along the lateral corridors. If no trees, snags or other obstructions blocked the path of a turn, the chokersetter signaled the yarder operator to yard the logs in at full speed. however, If any obstructions threatened to block the path of a turn, the chokersetter would signal to pull the turn in slowly to the skyline corridor. 32 6) Reset (in minutes) Average time per turn = 0.35 minutes Standard deviation = 0.793 minutes Standard error of mean = 0.038 minutes Because of the. infrequent nature of this &ement, no significant regression equation can be generated. The impact of this element can be minimized by the chokeretter anticipating probable hangups and stopping the turn before it becomes jammed and requires considerable time to reorganize the logs in the turn. minimize damage to residual trees. Rapid action will also The probability of resetting being necessary tended to increase as the number of logs per turn increased. Of the one-log turns observed, 21 percent required resetting, while 24 percent of the two-log turns and 26 percent of the three-log turns required resetting. 7) Inhaul Time (in minutes) H0: Inhaul f(SLPDST, SKYHT, GRDSLP, NOSUP, VOL) Inhaul 0.0841 n = 0.00201 * SLPDST 0.01178 * SKYHT - 0.0754 * NOSUP (standard units) Inhaul = 0.0841 0.00659 * SLPDST 0.03863 * SKYHT - 0.0754 * NOSUP (metric units) 549 R2= 0.S6 33 Addition of the other two variables increased the R2 value by less than 0.01 and so the above equations were accepted. Position Time (in minutes) Average time per turn Standard deviation n = 549 0.12 minutes = 0.330 minutes Standard error of mean= 0.015 minutes Because of the random nature of this element, no significant regression equation could be generated. Unhook Time (in minutes) H0: Unhook = f(DKHT, NOCKS) Unhook = 0.1512 n = 549 R2= 0.197 + 0.02657 * DKHT + 0.1116 * NOCKS (standard units) Unhook = 0.1512 + 0.08715 * DKHT + 0.1116 * NOCKS (metric units) Deck height, in turn, may be described by the equation: Deck height = 2.467 + 0.0588 * NOLGS (standard units) Deck height = 0.752 + 0.0179 * NOLGS (metric units) = 505 R2=0. 714 34 The relatively high R2 obtained indicates that the deck height required to stockpile a given number of Togs may be predicted with some confidence and may be used as an aid to layout design in stands with similar piece size material to the one studied, if cold decking will be necessary. Sort Rigging (Operator) Time (in minutes) Average time per turn = 0.07 minutes Standard deviation = 0.294 minutes Standard error of mean n 549 0.013 minutes Because of the random nature of this element, no significant regression equation could be generated. Decking Time (in minutes) Average time per turn Standard deviation = 0.36 minutes n 549 0.939 minutes Standard error of mean = 0.042 minutes Because of the random nature of this element, no significant regression equation could be generated. The maximum number of logs cold decked during the study was 210, and the maximum deck height measured was 16 feet (5 metres). With regular flattening to maintain a safe deck, may be decked without serious problems. 200-220 logs The major problem encoun tered with cold decking during the study was the lack of operator vision when the deck became higher than 10 feet (3 metres). 35 Figure 10 illustrates two adjacent deckz, each with approximately the same number of logs. One haz been flattened regularly by the yarder operator with a peavy, while the other has not been maintained at all. 12) Total Time per Turn (in minutes) The estimated time per turn (without delays) can be derived in two ways: by combining the individual element times discussed above for a given set of variable values; or by deriving a single regression equation with the total time per turn as the dependent variable and one or more of the measured independent variables as the independent variable(s). The second method is uzed in this paper as the generation of a single production equation enables statistical data to be calculated and used in evaluating the usefulness of the equation. Time per Cycle (in minutes) H0: Time per cycle = f(SLPDST, SLPOST2, LATDST, LATDST2, NOLGS, SKYHT, NOCS, GRDSLP) Time per cycle = 1.6932 + 0.005119 * SLPDST + 0.025653 * LATDST + 0.2783 * NOLGS (standard units) n = 549 0. 290 36 Figure 10. Example of a maintained and a neglected deck. V 37 Time per cycle = 1.6932 + 0.01679 * SLPDST + 0.08414 * LATOST + 0.2783 * NOLGS (metric unitz) The above equation is used in the derivation of the potential production rates presented in Figures 15 and iSa. Delays A summary of the delay times measured during the study, and the percent of total study time is presented in Table 7. The 8700 minutes of operations studied included both thinning and clearfelling operations. It is not poszible t sort many of the delays, especially those related to rapes, carriage and mechanical, intQ those resulting frrn thinning and those resulting frrn clearfelling operations. It is considered that the total operational delays of 26.1 percent of working time is a high figure, and could be reduced significantly by an experienced crew operating in smallwood. Delays which might be reduced include: Prepare the crew spent almost 4 percent of the total working time preparing for work. This included refueling, hooking up the signal system, and personal preparation. If a signal system was attached to the tractor permanently, some of this time could be saved. Fell and Buck Fallen Snags - a total of 4.3 percent of operation time was spent removing hangups and snags. Much of this 38 Table 7. Delays Operational Code Experimental Time (mm.) Percent Time (mm.) Percent Prepare 334.1 3.8 61.1 0.7 Fell & Buck 191.6 2.2 Snags 177.8 2.1 Ropes and Carriage 408.8 4.7 11.1 0.1 Supports 174.9 2.0 1106.0 12.7 Mechanical 767.1 8.8 693.8 8.0 Deck 120.2 1.4 Personal 34.4 0.4 Unspecified 60.6 0.7 Radio 98.7 1.1 Other 292.3 3.4 2263.0 26.0 Total NB. 2269.5 Total Time Studied 26.1 = 8700 minutes I 3. work could be avoided by improved felling practices, and by the fallers making bucking cuts in fallen snags which will cause yarding problems. Ropes and Carriage - the majority of the 409 minutes recorded against this delay was spent resplicing broken rope. The mainline rope was not new when the operation commenced and it broke on a number of occasions during the study. It was observed that breaks often occurred during or soon after yarding loads larger than 40 cubic feet (1.13 cubic metres). The weight of these loads ranged from 2500 lbs. to 3500 lbs. (1140 to 1640 Kgs). Only 38 turns, or 5.6 percent of the total turns measured (including those from the clearcut alder) exceeded the above volume but it would seem that these turns contributed to excessive rope (and machine) wear. Figures 11 and 12 present turn volume distribution for the thinning and clearfelling operations. Mditional rope wear was probably caused by the yarder operator attempting to break out hung up turns and also by attempting to pull logs through fallen snags. Supports - if support configurations are designed before layout, there should be no need to adjust the jack height to insure the skyline sits in the jack. Mechanical - most of the 770 minutes recorded as mechanical downtime was the time taken to repair or replace the main winch drive chain. Again, it was observed that chain links broke during the yarding of the larger turn volumes. 40 Average volume = 21.0 cubic feet (0.59 cubic metres) 50 (1, 0 S.- 3O C 20 0 0-10 1-1.3 11-20 0.3-0.6 21-30 0.6-0.8 31-40 0.8-1.1 41-50 5]+ (cubic feet) 1.1-1.3 1.4+ (cubic metres) Volume Per Turn Figure 11. Distribution of turn volumes - thinning Average volume 22.8 cubic feet cubic metres) (0.65 50 40 301 20! 10 '1, 0 0-10 0-0.3 11-20 0.3-0.6 21-30 0.6-0.8 31-40 0.8-1.1 41-50 1.1-1.4 51+ 1.4+ Volume Per Turn Figure 12. Distribution of turn volumes - clearfelling (cubic (cubic feet) metres) 41 Reduction of these large volumes and the avoidance of breaking out 'hung up turns with the machine may reduce chain wear. It has been noted in a later study of the Alp (during which the drive chain continued to cause downtime) that some bolts holding the winch to the trailer franie were loose. This caused the chain to stretch unneces- sarily, and may have been the cause of so much chain wear in this study. Road Changes With only seven observations, any regression equation which correlates road change time with all four of the above variablez will produce an artificially high R2 value. However, it was apparent to the obzerver that the slope distance was a major factor in road change time, and so an equation has been generated which correlates road change time slope distance (Table 8). Road change time -162.76 + 46.5455 * ln SLPDST n=7 R2= 0.305 This equation has been uzed in the derivation of the potential production rates presented in Figures 15 and lSa. The road change time, at nearly 10 percent of total working time, is a significant non-productive operating element. This time might be reduced if: Guy treez were selected and felled prior to a road change. The rigging out element was better coordinated so that maximum use was made of available man power. Table 8. Change Rig Guys No. In In Move Yarder Guys Out Road Changes (All times in minutes) Rig Out Raise Jacks Total Move OST No Supj. SIP OST (ft) (m) (ft) (m) Crew Size 1 11 16 4 - 70- 18 119 275 84 27 8 1 3 2 13 3 8 - 123- 10 157 515 157 130 40 1 3 3 23 11 3 28 72 137 425 130 165 50 0 4 4 13 9 2 22 81 127 460 140 180 55 0 3 5 11 5 5 15 24 60 260 79 175 53 0 3 6 8 7 8 40 39 9 111 660 201 260 79 1 3 7 15 11 14 7 65 14 126 580 177 830 253 2 3 Total Time Average Time Percent of Total Time 837 minutes 119.6 minutes 9.6 minutes 43 During six road changes, guylines were tightened by using manual pre-tightener with the Alp utility winch used to hold the trailer over towards the guytimps. The winch brake was then released to lower the trailer and tighten the guys. During the last road change studies, portable hand winches were used to tighten the guys (Figure With crew familiarity, these winches may reduce road change 13). times. Guytrees were selected and prefelled before road changing on this road, so the short (seven minute) guy out element could not be attributed directly to the tighteners, but as the crew becomes familiar with their use, they may reduce guy tightening time. Table 9. Surrnary of Time Usage Operating Delays Percent of Total Time 26.1 Road Changes Utilization 9.6 64.3 Niachine Machine availability is calculated as 84.5 percent Intermediate Supports Details of the two rig support operations measured are located in Table 10 on page 45. The rigger recorded gross measurements on the trees he prelimbed. Table 11 lists data for six trees. These trees were limbed only, and the support blocks were hung at a later time. included climbing, limbing, and The times listed the rigger returninq to the ground. 44 4 Figure 13. Line tightener for guylines I 45 Table 10. Rig Support Times Element (All times in minutes) Support Number 2 1 Move in equipment 16 15 Climb, limb, and rig 12 15 17 14 3 2 Anchor support line 10 S Total Time 58 51 tree 1 Climb, limb, and rig tree 2 Move between trees Number of limbs cut #1 Not recorded Not recorded 51 #2 Height of blocks 25 25 #1 #2 Table 11. Tree No. 36 30 Support Tree Limbing Times Height No. Limbs Time (mm.) 1 20 52 6 2 20 48 10 3 30 20 10 4 30 34 6 5 25 69 10 6 25 29 9 Average 25 42 8,5 46 During the study, most of the limbs removed were small and generally dead. The only reason for removing them was to allow the rigger to climb the tree. In a recent study (Gibson and Fisher, 1977) which involved the use of supports, riggers used Swedish climbing ladders to hang support blocks. Their use in the Northwest for this purpose may reduce the total rigging time as the number of limbs require.d to be cut could be reduced, and the need to limb may even be eliminated. Some time was lost during the study adjusting the height of the support jack so the skyline would sit on it when tensioned. However, the lateral placement of the jack in relation to the skyline corridor seemed relatively flexible. With the jackblock riding freely on the support line, it could move laterally to compensate for any lack of symetry in support block height or support tensions. Support blocks were hung 20 to 35 feet (6 to 10 metres) from the ground in support trees 15 to 30 feet apart, and perpendicular to the skyline road. The jack was positioned 15 to 20 feet (4 to 6 metres) above the ground (Figure 9). Potential Production A computer program has been written in BASIC language for use on the Hewlett Packard 9830 desk-top computer to derive potential daily production rates for the Igland-Jones Trailer Alp thinning stands similar to the one studied. The program calculates production rates by: 47 Figure 14. Swedish climbing ladder - Virginia Study 48 accepting input data including the number of stems per acre cut, the number of pieces per tree, the volume per piece, the number of pieces per turn, and the total delays expected (as a decimal). calculating the expected time per turn (without delays) using the equation described on page 35. calculating road change time for the slope distance being considered. calculating the total time to yard one road, by deriving the area of the road and the total number of turns per road, and multiplying the number of turns by the time per turn. Road change time is added to this. calculating an effective total time to thin one skyline road including yarding, road changes, and delays. The hourly priduction rate is derived by dividing the total volume in a road by the time taken to yard the road. Using this program, the production graphs presented in Figures 15 and lSa have been developed. It can be seen that at an average slope distance of 250 feet (75 metres) and with an average lateral yarding distance of 35 feet (11 nietres), the anticipated hourly production is 175 cubic feet (5 cubic metres) per hour. This translates to a daily eight hour priduction of 1400 cubic feet (40 cubic metres) or 109 pieces per day if the average piece size equals 12.9 cubic feet (0.36 cubic metres). 49 In a study of a Trailer Alp operating in British Columbia, Maxwell and Oswald (1975) report that the machine yarded an average of 190 logs per eight hour shift, with an average yarding distance of 270 feet (80 metres). The operation thinned a western hemlock stand, removing 177 stems per acre (437 stems per hectare). This compares with the study figure of 96 stems per acre (237 stems per hectare). The average number of logs per turn in the Canadian operation was 2.1 compared with the present study average of 1.6; a difference probably due to the large number of stems removed in the forTner operation. The average turn time in Maxwell's study at 4.8 minutes, is similar to the current study average of 4.5 minutes. The higher daily piece count is most likely explained by a combination of the higher number of pieces per turn for the Canadian study and the lower operating delay loss--less than 20 percent compared with an estimated 26.1 percent in this study. 50 Average Slope Distance (ft) 182 L2 t72 L) = w 96 Trees per acre removed L3 = = 1.5 Logs per tree = Volume per log (cuft) = 12.9 Logs per turn = LL12 26.1 Delays (percent) L4 1 .6 7 VAE LTRRL DETRN(E (FT.) Figure 15. Production per hour as a function of lateral and slope (standard units) distances. 51 Average Slope Distance = = 237 Trees per hectare removed = Logsper tree = 1.5 Volume per log (cu.rn) = 0.36 Logs per turr = 1.6 Delays (percent) = 26.1 - 12 RVERFE LTL ISTRN(E Figure 15a. t9 21 CM.) Production per hour as a function of lateral and slope distance (metric units). 52 Table 12. Daily Operating Costs - 8 Hour Day Trailer Alp Tractor Saws at $6.13 per day each Transport (40 niles - 25 kilometres one way) Radio Labor (including fringe benefit factor of 39 percent) (USFS, Region 6 Lead Cutter @ $12.27 per hour 2 3man 4man crew crew $92.93 $99.36 26.47 28.01 - 12.26 2 - 12.26 16.22 22.76 5.58 5.58 1976) 98.16 98.16 - 97.52 Second Cutter @ $12.19 per hour Chokersetter (radio) $9.30 per hour (a) 74.4.2 69.52 Yarder Operator @ $10.34 per hour (a) 82.72 79.60 408.76 512.77 Total Daily Cost Daily Production Cubic Feet Cubic Metres Board Feet Unit Cost on Ride Per Cunit Per Cubic Metre Per Mbf. (a) Paid second cutter rates while falling. 1158 32.8 6950 1400 40.0 8400 $35 .30 1 2.46 $36.63 12.93 58.83 61 .04 53 DISCUSSION OF RESULTS Productivity The results of the production study, in conjunction with personal observations would indicate that the Igland-Jones Trailer Alp yarder has the ability to perform succe.ssfully thinning young growth stands of Douglas-fir. However, the operation of a small yarder in smallwood requires different skills and different operating techniques than the large machines which have been so effective in the Pacific Northwest. With limited power available, it is not desirable, and in many instances not possible, to open the yarder throttle and expect hung up turns to be pulled free of hang ups or pulled obstacles. through other Although the Trailer Alp did not appear to be loaded to its power capacity during this study, with heavier thinning intensities or larger piece material it will be important that the chokersetter does not overload the machine--a situation difficult to achieve with many of the large yarders currently being used. It is very important that each crew member is familiar with all facets of the thinning operation. The financial viability of the thinning operation may be determined by the skill of the fallers. These fallers avoid hang ups while falling trees to lead and should ensure that no immovable obstacles remain in the skyline or lateral corridors. The chokersetter must select his turns so that they will have 54 He should also a relatively free path to the skyline corridor. be ready to stop the inhaul cycle to reset the turn if it hangs up. In turn, the yarder operator must appreciate the limits of his machine and should not overwork it. Because of the tighter limits placed on logging practices when using such a small machine, it may be desirable that each crew member rotate work positions so that he can appreciate the skills involved in perfrrning each function efficiently. It was noted in the analysis that the addition of a second chokersetter had only a small iiiipact (a saving of 0.10 minutes per cycle) on the lateral out element and did not enter the hook regression equation as a significant variable. The number of chokersetters was not a major variable in the total turn time regression. This result would not be expected but may be explained by the following reasons. A second chokeretter was used at slope distances greater than 300 feet (90 metres). Because of the greater force required to pull slack as slope distance increased, he did not speed up the lateral out element, but did enable slack to be pulled at distances where a single man would not have been able to operate by himself. The hook element included the time taken for the chokersetter(s) to move to safety after setting the chokers. When a single chokersetter was operating, he often signaled for the beginning of the inhaul elements before he was safely away from the turn, relying on his agility to get out of the way before the turn moved. 4 55 When two chokeretters were working, however, the one with the radio did not signal until both men were safely out of the path of This delay tended to nullify the effect of the chorter the turn. hook time. Sensitivity of Production The sensitivity of the potential production rate to a change in one or more of the variables used may be deteriiiined quickly by the use of the Hewlett Packard 9830 program listed in Appendix 2. The following figures indicate the variation in production rates per hour expected by a change in important variables. In Figures 16 and 16a, the volume per piece is varied between 11 and 17 cubic feet, and 0.31 and 0.49 cubic metres, rspectvely. The derivation assumes: Sterns removed = 96 stems per acre (237 stems per hectare) Pieces per tree = 1.5 Pieces per turn 1.6 Operating delays = 26.1 percent In figures 17 and 17a the expected operating delays are varied between 17 and 26 percent. The above assumptions hold (except for No. 4) and the volume per turn = 12.9 cu.ft. (0.36 cu.m). Lateral Yarding Lateral yarding is a major work activity of the yarding cycle. One man was able to pull mainline relatively easily out to 100 feet Volume per piece in cubic feet 17 I -1 LU IWU 1W 2UW HVERHEE 5LUPE 1IiTHNCE (FT.) Figure 16. Production per hour as a function of slope, distance and vo'ume per piece (standard time) 3UW Voluiue per piece in cubic metres zEi Dr L12-.t I!: EL1 7 RYERRIE SLUPE 1I5TRN(E CM.) Figure 16a. Producti0r per hour as a function of slope distance and volume per piece (metric units) U1 F- H Percent Delays Li 17 a: r I!1L1 a: Li ci IIElkl 23 D a: 25 17k1 R1L4 Figure 17. 2E IL1 2LI HVEFFIFiE SLIJFE LIiTHNCE (FT.) Production per hour as a function of slope distance and percent delays. (standard units) 31LI - .E1 =1 Percent Oelays Et LI 17 L4 P-r2I 23 9.F 7 HVEHFIIiE Figure 17d. LE1PE t?ITHNCE (M.) Production per hour as a function of sope distance and percent delays. (metric units) 60 (30 metres) laterally at a slope distance of 500 feet (150 metres) on slopes greater than 20 to 25 percent. A second man was required at slope distances greater than 500 feet (l0 metres) or, on flatter ground, at shorter slope distances. To estimate the amount of force required to pull line at varying slopes and slope distances, the following equation may be used (1ff, 1977). F=W*L (rCosGtSinG) where F = The force required to pull zlack (in lbs. or kg.) W = The unit weight of mainline (in lbs/ft or kg/m) L Slope distance (in ft. or m. r = Coefficient of kinetic friction between the mainline and the ground 9 = Groundslope in degrees. The value of r may vary depending on ground conditions. wet conditions in this area, r = 0.. Under Under wet conditions this value has been measured to be 0.43 (1ff, 1977). Some of the assumptions made in derivation of this equation may not hold true for all yarding conditions, but field nieasurrnents have confirmed its validity under a variety of conditions. The use of this equation illustrates the effect of both groundslope and slope distance on the amount of force required to pull line. For example, the amount of force required to pull a 3/8 inch (1 centimetre) mainline on a 40 percent downhill slope 500 feet (150 metres) from the tower is 18 lbs. (8 kg.). On a 10 percent I 61 downhill slope at the same distance, the force required is 58 lbs. (26 kg.), and on a 20 percent uphill slope the force is 96 lbs. (43 kg.). The graph presented in Appendix 3 can be used to determine the approximate line pulling effort required to pull mainline from the carriage at varying slope distances and steepness. Intermediate Supports The use of intermediate supports solved two major problems in the study area. It enabled the yarder to extend 4.00 feet (20 metres) further than it could have without supports on four of the skyline roads. When placed within 100 feet (30 metres) of the landing, it facilitated efficient decking and enabled decks of more than 200 logs to be built up without excessive decking delays. The crew bent three jacks while lateral yarding within 20 feet (6 metres) of the support line when the line was passed directly through the yolk of the jack. Following this experience, the jack was hung from a block which enabled the jack to move freely along the support line, and no further problems were observed, although generally the Alp support jack and carriage worked successfully during the study. Crew Size During the study three men were available for the yarding 62 operation. All three men assisted with road changing and in one change a fourth man assisted the regular crew. The crew managed to keep ahead with falling and bucking because of numerous mechanical problems to the Trailer Alp which occurred before the study period began. However, in a production situation, the balance between crew size and production would need to be analyzed. A comparative production and cost analysis for a three and four man crew has been presented in this paper (see Appendices 9 and 10, and Table 12). Gross measurements taken during the study indicated that an average of 10 logs were felled, limbed, and bucked per man hour (see Appendix 11). The fallers were not under pressure to keep ahead of the yarder, however, and so this figure has not been used for analysis. A recent study of felling and bucking in similar material (Aulerich, 1975) reported that the average time per tree taken to fell, buck, and limb was 7.52 minutes. This translates to eight trees per man hour or 96 logs in an eight hour day. Using this figure, production and ccst estimates have been calculated for a three and a four man crew yarding out to 500 feet (150 metres) and lateral yarding out to 70 feet (21 metres) on each side of the skyline corridor. The results indicate that a three man crew produces less than a four man crew because of the need for the chokersetter and yarder operator to supplement falling production but that the unit cost of logging with a three man crew is less than with a four man crew (Table 12). 63 Stand Damage A quantitative assessment of damage to the residual stand was undertaken as part of the study. It was observed, however, that the damage to residual stems tended to be more prevalent and serious as the number of stems per turn increased. One of the three choker- setters observed tended to 1bonus" as many turns as possible by the use of sliders. This practice may increase productivity, especially in areas where logs are scattered, but this advantage should be weighed against the extra stem damage which may result from the reduced control the operator has over the turn. Additional sources of stem damage were the straps used to hole corner blocks, tail blocks, and those used to anchor intermediate support ropes. The half-inch straps used during the study ringbarked the trees to which they were attached (Figure 15). This damage would be prevented by the use of protective rubber strips cut from auto tires or similar material. 64 4 Figure 18. Example of ringbark damage 65 FUTIJRE STUDIES The Forest Engineering Department of Oregon State University has already completed field data collection of the Trailer Alp yarding clearfelled timber on a road right-of-way-out to 1000 feet (300 metres), using two intermediate supports and with haulback line. Also, data has been gathered for a hardwood clearfelling operation where a 150 lb. (46 kg.) gravity outhaul system. 'Mini Christy' carriage was used with a These studies have yet to be evaluated, but preliminary results of the Christy carriage study indicate that the gravity outhaul system can significantly increase productivity if intermediate supports are not required. Two design modifications might be analysed: The Trailer Alp, currently powered by a farm tracor, could be adapted so that it is powered by a separate engine built onto modified trailer. a The unit could be moved with a small skidder which could also swing logs away from the deck. Major production increased may be achieved if a gravity outhaul clamping carriage can be modified so that it passes over intermediate supports. The combination of a clamping carriage with a gravity outhaul system would probably generate a large amount of interest in the Pacific Northwest. 66 CONCLUS ION The Igand-Jones Trafler Alp has been tested thinning young growth Douglas-fir in Western Oregon. During the study period the Trailer Alp was used with a standing skyUne configuration and inter- mediate supports were used on four of the seven skyUne roads observed to obtain additional deflection on unfavorable slopes. The study was conducted only two weeks after the machine was delivered to the yarding crew and many of the mechanical and operating system delays measured were caused by crew unfamiUari]y with the equipment and the experimental nature of the system. Where possible, experimental delays have been removed from the analysis, but their effect in disrupting the work patterns of the crew effectively reduced the overafl productivity of the system under study. Because of this problem, the production estimates presented in this paper wou]d represent a lower limit of what could be expected from an experienced crew under similar operating conditions. The niajor objective of the study--to develop production equations which may be used to estimate production over a range of conditions--. has been achieved. It has also been demonstrated that intermediate supports can be used successfully with the Trailer Alp to extend yarding distance and permit yarding operations on long or convex sI opes. A detafled analysis of intermediate support design is currently in progress at Oregon State University and the results from this 67 analysis should be valuable in determining the effective design of and safe limits for intermediate supports in young Douglas-fir. 68 BIBLIOGRAPHY Smallwood Harvesting Research at Oregon State 1975. Aulerich, D.E. Loggers Handbook, Vol. XXXV, 10-12, 84-88. University. Economics of Using a Small 1977. ibson, H.F. and E. L. Fisher. European Standing Skyline to Partial Cut Eastern U.S. Hardwoods. U.S. Forest Service, Morgantown, West Unpublished report. 35 p. Virginia. An Analysis of the Slack Pulling Forces Encountered 1977. in Manually Operated Carriages. Masters Thesis, Oregon State University. 65 p. If-F, R. H. A Case Study for Pre-bunching and Swinging. 1976. Kellogg, L. D. A Thinning System for Young Forests. Masters Thesis, Oregon State University, 88 p. Cable Logging in Norway, A Description Lisland, Torstein. 1975. A paper presented as of Equipment and Methodz in Present Use. a Visiting Scientist at Oregon State University, Forest Forestry Northwest Area Foundation. Engineering Department. Series. 47 p. Tree Volume Tariff Access Tables for Pacific 1972. Little, G. R. Vol. 2, Major Coastal Species. State of Northwest Species. 163 p. Washington, Department of Natural Resourcez. 1975. Maxwell, H. G. and D. Oswald. Succezsful in British Columbia. Vol. 49, 62-66. Cable Yarder Thinning Proves Canadian Forest Induztries, Comprehensive 1972. Turnbull, K. J., G. R. Little, and G. E. Hoyer. State of Washington, Department of Natural Tree Volume Tables. Resources. 320 p. Department of Agriculture, Forest 1974. U.S. Forest Service. Products Laboratory. Wood Handbook. Wood as an Engineering Material, 356 p. Department of Agriculture. Timber 1976. U.S. Forest Service. Appraisal Handbook, Region 6 Chapter. 416-482, 100 p. 69 APPENDICES 70 Appendix 1 Profiles of Skyline Roads Studied Scale 1" = 130 feet (1 cm = 16 m) 2 1 a 7 a I a 9 (5) 7 (6) 2 I 2 3 1 * Intermediate supports used 71 Appendix 2 Hewlett Packard 9830 Computer Program to Calculate Estimated Production per Hour (cubic feet) Under Varying Conditions 3 .'i 4' ,:33,jL2) 11;iqr :.::.:I ,7,:3... 'J R:..:I3 LEL F' PLT T ::::=1J T i':' TE CLOT -i-2 Lt LtBEL t NE::1 ii = L21 PL31 i, 1 i43 -'U ,37P 1 L.5-3.3 CPLO PLOY L:,It,t i TGE .HTi_ t:E:i L9EL L.2. L.79.3.i..' t?i LCT L'L4.: _tii _-i'_ fl rT I I1 l 11 ?SL i I r rtt. L- 1 .i..: T:i 24 h'CJT' 2$cj .t4PtJT '4 P 27 P Z T!, JL INF'JT PL1D 3ii FC..:!O .J:3 291 FOP L.L :21 ..1&d*F" - flil t -'- i 2Ft'L1 " ' :.. _ T1jPi Z) :T? =4:4L) ..4:333 : LI 9L + + C=L... #4. 3 ' F11AT 4 .1 4: 4t - L LT LL 47Zi L.EL 5Li L. ::r L 4i OF..OT :i.:. -cj.. 49k) 4 t i::i LiTTP 1. t.Th .......2: . ¶ F r = W IWW Appendix 3. = Percent slope 0.55 0.26 lbs/ft IEL1 PJ1ø 2ø '-tI1Ii IL1 WI L1JFE tITRr'ICE (FT.) 9SW SWW Ek1 Line Pulling Force as a Function of Slope Distance and Percent Slope (standard units) EiWkl Percent slope2 r = 0.55 W 0.39 kgs/m. LIIti 2L1 9LI 3t1 EiLl 7S E114 12L1 tJ5 IEiE IF11 5LEJPE DLTHNCE CM.) Appendix 3a. Line Pulling Force as a Function of Slope Distance and Percent Slope (metric unit) 74 Appendix 4 Daily Cost - TrailerAlp Yarder New Cost (NC) $46,000 Resale (4 yrs, 25 percent) (S.V.) Net Cost 11,500 $34,500 Average investment = (NC + Dep. + S.V.) 2 Fixed Costs Depreciation (Dep.) $ 8,625 Interest (12 perc2nt of average investment) 3,967 Insurance (2 percent of average investment) 66 Taxes, etc. (4 percent of average investment) 1,332 14, 585 Operating Costs Repairs and Maintenance (50 percent of depreciation) $ 4,312 Tires 50 Hydraulic Oil 200 Rigging S/L 900' of 5/8 x $.667/ft. 600 M/L 1800' of 3/8h1 x $.392/ft. 706 H/B 1800' oq 3/8" x $.392/ft. 706 Chokers, 20 at $20 400 Tools and Miscellaneous 300 $ 7,274 Total Annual Cost $21 ,859 Total Daily Cost (at 220 days per year) $ 99.36 75 Appendix 5 Daily Cost - John Deer 2640 Farm Tractor New Cost sis,000 Resale (8 yrs, 10 percent of NC) 1,800 $16,200 Average investment = $10,912 Fixed Costs Depreciation $ 2,025 Interest (12 percent of average investment) 1,309 Insurance (2 percent of average investment) 218 Taxes, etc. (4 percent of average investment) 437 $ 3,989 Operating Costs Fuel - 220 days x 6 hrs, x 1 gal. x 5Ot 660 Oil and Lubrication 300 Repairs and Ma.intenanc (50 percent of depreciation) 1 ,013 Tires 200 $ 2,173 Total Annual Cost $ 6,162 Total Daily Cost $ 28.01 76 Appendix 6 Daily Cost - Crew Transportation 3Man 4Man Crew Crew $5,000 $7,000 2,500 3,500 Net Cost $2,500 $3,500 Average Investment $4,166 $5,833 833 $1,167 Interest (12 percent of average investment) 500 700 Insurance (2 percent o-P average investment) 83 117 167 233 $1,583 $2,217 Fuel - 80 mls x 15 mpg x 220 dys x 65t/gal. $ 763 $1 ,144 New Cost Resale Fixed Cost Depreciation $ Taxes (4 percent of average investment) Variable Costs Repairs and Maintenance (50 percent of depreciation) 833 1,167 Oil and Lubrication 150 200 Tires 240 280 $1 ,986 $2,791 Total Annual Cost $3,569 $5,008 Dafly Cost $ 16.22 $ 22,76 77 ADpendix 7 Daily Cost - Chainsaws Each $400 New Cost Resale (1 yr) $400 Net Cost Average Investhient = $400 Fixed Costs $400 Depreciation Interest (12 percent of average investment) 48 Insurance (2 percent of average investment) 8 16 Taxes (4 percent of average investment) $472 Operating Costs $400 Repairs and Maintenance (100 percent of depreci ati on) Fuel 1 gal/dy x 220 dys x S5 121 011 1 pt/dy x 220 dys x 75t 165 Chain 9 chains x $20 180 $866 Total Annual Costs $1 ,348 Daily Costs $ 6.13 78 Appendix 8 Daily Cost - Radio "Talkie Tooter' New Cost $3,500 Resale (5 yrs) New Cost Average Investment $3 , 500 $2,100 Fixed Costs $ Depreciation 700 252 Interest (12 percent of average investment) 42 Insurance (2 percent of average investment) 84 Taxes (4 percent of average investment) $1 ,078 Variable Costs Batteries, etc. $ Repairs and Maintenance 5J 100 $ 150 Total Annual Cost $1 ,228 Daily Cost $ 5.58 79 Appendix 9 Determination of Production and Cost Data for a Three Man Logging Crew Assumptions Average yarding distance 250 feet (76 metres) Average lateral distance = 35 feet (11 metres) Felling productivity = 12 logs per man hour Faller assists chokersetter for final 10 percent of the road One road in three requires a multispan Multispans are pre-rigged by the faller with a total time lost of 1 hour, 15 minutes Net Productivity of Faller Gross productivity (8 hour day) = 12 logs per hour Yarder production per day = 1400 cubic feet (40 cubic metres) = 109 flieces = 13.6 pieces per hour No. of pieces per road 231 A road change is required every 2.12 days Time faller must spend chokeretting = 0.80 hours per day Time faller must spend rigging 0.20 hours per day Time faller must spend on road changing = 0.99 hours per day Non-productive time 0.80 + O2O + 0.99 Production per day (8 hours) = 72 logs - 1.99 hours per day t 80 Net Daily Production of Yarder Yarder will log above production in 5.3 hours Time left = 8 - 5.3 - 2.7 hours To balance this time between yarding and cutting: Let x = no. a-P hours falling by machine operator and chokers etter Then 12 x 13.6 (2.7 - x) x = 1.43 hours i.e., the yarder operator and chokersetter must fall 1.43 hours per day to provide logs for an additional 1.3 hours per day yarding. Total yarding time = 5.3 + 1.3 6.60 hours Net daily production = 1158 cubic feet (33 cubic metres) Yarding Cozts The fixed and variable costs for the yarder and tractor are revised to reflect the reduced working time. The resale value of the machines is increased by 15 percent and the variable costs are reduced 1.5 percent. -i 81 Appendix 10 Net Production Rate for a Four Man Crew Gross Yarder Production = 109 pieces Cutting Production = 1 man full time 1 man (as for 3 man crew) 12 x 8 96 pieces 72 pieces 169 pieces i.e., felling capacity exceeds yarding capacity. The net yarding capacity can be derived directly using HP 9830 program. 82 Appendix 11 Table of Gross Time Measurements of Felling and Bucking Productivity Record No. Time On Time Off No. of Mins. No. of Logs Logs per Man Hour 1 7-10 11-30 260 54 12.5 2 7-30 11-30 240 41 10.3 3 3-15 11-30 255 37 8.7 4 3-15 11-20 245 42 10.3 5 3-00 4-30 90 9 6.0 6 3-30 4-46 196 42 12.9 7 12-36 4-46 250 41 9.8 8 9-00 11-30 150 24 9,6 9 7-45 11-30 225 28 7.5 1 0 1 2-15 5-00 285 51 1 0 7 11 7-15 11-30 465 55 7.1 12-00 3-30 12 8-00 11-25 205 46 13.5 13 3-15 5-50 135 17 7.6 n = 13 Mean logs/hr = 9.73 SE = 0.645 = 5.0% of mean