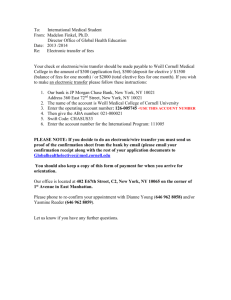

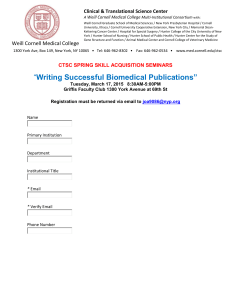

weill medicine cornell

advertisement