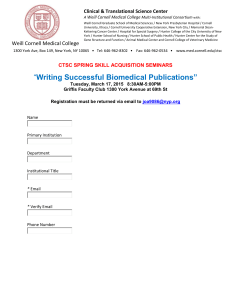

weill medicine cornell

advertisement