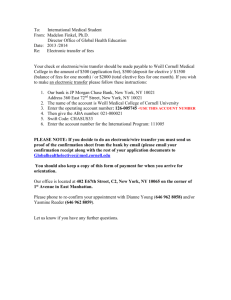

weill medicine cornell Dressed

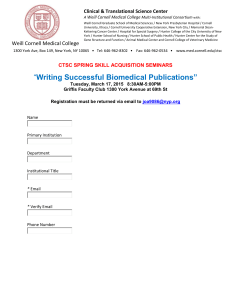

advertisement