weill medicine cornell

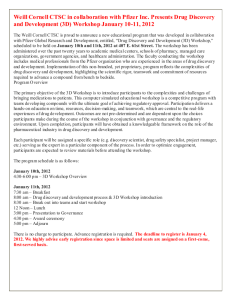

advertisement